JOHN PILGER: The article below by Chris Graham, editor of New Matilda, appears on my initiative. 21 June, 2017 was the 10th anniversary of John Howard’s invasion of Aboriginal Australia. Known as “the intervention”, this national disgrace destroyed the vestiges of Indigenous self-determination across the Northern Territory and had a devastating effect on communities; most have yet to recover.

It was justified with and made possible by propaganda – distortions and lies. The Australian media played a vital role, notably the ABC.

This week is also the 11th anniversary of the media story that ignited Howard’s disaster. In June 2006, the national TV current affairs programme, the ABC’s Lateline, broadcast a sensational interview with a man whose face was concealed. Described as a “youth worker” who had lived in the Aboriginal community of Mutitjulu, he made a series of lurid, bizarre and false allegations.

Subsequently exposed as a senior government official who reported directly to the minister, Mal Brough, his claims were discredited by the Australian Crime Commission, the Northern Territory Police and a damning report by child medical specialists. The community received no apology.

Chris Graham exposed this in the newspaper he helped found, the National Indigenous Times. I would class his scoop as among the most important and courageous journalism I have known – courageous because he broke a taboo and revealed the media’s collusion in the enduring suffering of Indigenous people.

I asked Chris to run again his investigation. He has updated and consolidated it into one piece. I salute him.

– John Pilger, June 19, 2017

A Howard government policy that decimated Aboriginal communities in 2006 is still reverberating today. New Matilda editor Chris Graham takes a look at a scandal that the ABC would rather you not hear about.

Self-praise is really no recommendation, so, in 2011, when television personality Tony Jones described ABC Lateline’s 2006 coverage of sexual violence in remote Northern Territory Aboriginal communities – reporting which led directly to the 2007 Northern Territory intervention – as among the best he’d ever seen, I was a little underwhelmed.

Jones, of course, is the former anchor of Lateline, now the face of the popular Q&A program.

My sense of unease wasn’t helped by the fact that Lateline’s coverage proved extremely popular with politicians.

Generally speaking, when conservatives get ‘excited’ about Aboriginal affairs, some blackfella somewhere in the country is going to get screwed. But excited they got, and few more so than Dave Tollner, former Country Liberal Party MP, and the one-time Member for Fong Lim, in the Northern Territory parliament.

In my career, I’ve only ever had one encounter with Tollner. It was in Alice Springs in 2009, when the Northern Territory parliament moved south to Alice Springs for a session, to ‘bring democracy to the people’. I sat in the public gallery directly behind Tollner throughout much of the proceedings. For several days I watched him surf Facebook on his laptop. Occasionally, he’d leap to his feet to direct some class-clown barb at the Opposition, only to sit back down and resume the Facebook hunt.

In fairness to Tollner, while his internet habits ultimately led to the website being banned during sittings of NT Parliament, he does have a more serious side.

In October 2011, Tollner appeared on the Q&A program, filmed in Darwin and hosted by Tony Jones.

After lamenting that there wasn’t a single hairdresser employed on either side of the Stuart Highway – evidence, apparently, that there was no economic development – Tollner weighed in on the meaty topic of the Northern Territory intervention. It came after co-panellist and Central Australian Aboriginal leader, Rosalie Kunoth-Monks had suggested that government needed to properly engage with Aboriginal people, “not hunt us like dogs”.

Jones invited a response from Tollner.

“Let’s put some things into context here Tony, and I do acknowledge your role in the intervention… ” said Tollner.

A clearly pissed off Jones interrupted. “I had no role in the intervention, that was done by a government.”

“No, no, no, but it was your show that lifted the lid on many of the problems that occur in remote communities and I acknowledge that,” replied Tollner. “That led to the major inquiry that resulted in the Little Children Are Sacred report, so I do acknowledge your interest in this area.”

As with so many things that Tollner says, it drew laughter and ridicule from the audience. But on this occasion, Tollner was right. Paradoxically, so was Jones.

The NT intervention was a government policy. The ABC is powerful, but it doesn’t yet have the power to send in the army. But Tollner was also partly correct. It was Lateline’s reporting that led directly to the Little Children Are Sacred report, a landmark inquiry into sexual violence in NT Aboriginal communities.

And it was the Little Children Are Sacred report on which the federal government relied to launch an unprecedented assault on the rights of the nation’s most disadvantaged people.

That, and the launch of their 2007 re-election campaign.

A desperate Prime Minister facing electoral annihilation

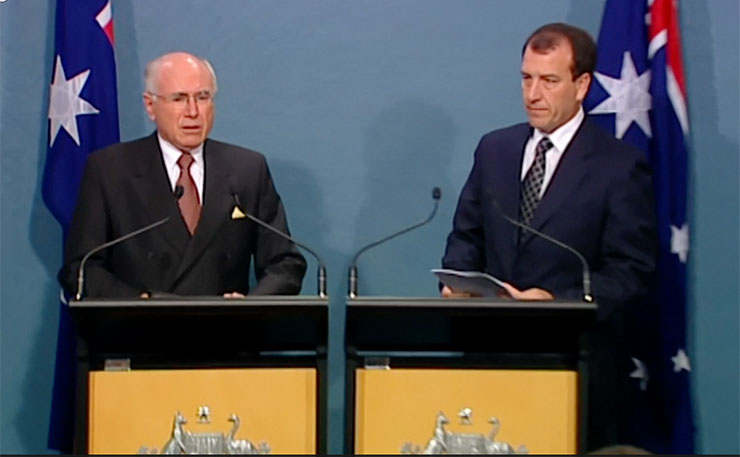

It’s now a matter of infamy that on June 21, 2007 – just a year after Lateline began a concerted campaign seeking to depict dysfunction, violence and paedophilia in NT Aboriginal communities – then Prime Minister John Howard, and then Indigenous affairs minister Mal Brough staged an impromptu press conference at Parliament House in Canberra, at which they announced Australia was confronting a “national emergency”.

There had, of course, been a “national emergency” in Aboriginal communities in the NT and beyond since Howard won office in 1996, and well before.

That the PM and his Aboriginal affairs minister had only just discovered it was quite remarkable. But it was nowhere near as shocking as what the two men were about to unveil.

The NT government had failed to act on the recommendations of the Little Children Are Sacred report, said Howard and Brough, and so the federal government was using its executive powers to intervene.

The Australian Army would be used to ‘stabilise’ Aboriginal communities, with extra police brought in to tackle the ‘endemic levels of child sexual assault’. Land in and around Aboriginal townships would be compulsorily acquired for five years, to ensure that Traditional Owners didn’t get in the way.

Howard even boasted that he would introduce “mandatory” sexual health checks of Aboriginal children, apparently believing at the time that his powers as Prime Minister extended to the legal rape of children.

After warning media the NT intervention would cost “some tens of millions” of dollars, and setting in train media coverage that would bounce around the globe, the serious business of unrolling the Northern Territory Emergency Response – more commonly known as the NT intervention – got underway.

The outcomes of the NT intervention are obviously important, and we’ll get to them shortly. But this story is really more about how it all came about.

The media hunt begins

Lateline’s interest began in early 2006, a full year before the intervention was announced, when it broadcast an interview with Central Australian prosecutor Nanette Rogers.

Ms Rogers, an experienced and respected legal practitioner, outlined shocking cases of sexual abuse of Aboriginal children which, over a period of more than a decade, had made their way through Territory courts.

She described toddlers and babies being raped; she described incest; men using traditional law to escape serious punishment; Rogers even referenced a case in which an 18-year-old petrol sniffer simultaneously drowned a young girl while he raped her.

For mainstream Australia, Rogers’ interview came seemingly ‘out of the blue’. It sparked massive media interest, which still endures today. That’s perplexing for anyone with even a brief knowledge of the history of government reports in Aboriginal affairs. Because the sorts of revelations that Rogers’ had unveiled were nothing new.

In 1989, Professor Judy Atkinson wrote a landmark report on Aboriginal violence, and in particular child sexual abuse. She wrote another one for federal government in 1991.

Professor Boni Robertson also completed substantial reports throughout the 1990s, and headed a major inquiry in 1999 which involved 50 senior Aboriginal women and represented every community in Queensland.

Between her and Atkinson, they warned politicians on numerous occasions of the problems in Aboriginal communities, and showed that the causes of family violence were rooted in a failure of government to provide basic services, investment and infrastructure.

Their reports were largely ignored, although, of course, they weren’t the only ones trying desperately to focus national attention on the growing problems in Aboriginal communities.

The Aboriginal And Torres Strait Islander Commissioner (ATSIC) – an Indigenous-elected government agency later abolished by Howard – also completed numerous reports in the 1990s, and in 1999 Dr Paul Memmott released a major report into Aboriginal violence, revealing precisely the sorts of cases detailed by Rogers, including the rape of young babies.

Memmott’s report went virtually unreported by media, due in no small part to the fact that when it was finally made public it was already old news.

The Howard government – courtesy of then Justice Minister Amanda Vanstone (later the Indigenous affairs minister) – sat on the report for 18 months.

A few years later, in July 2003, Howard staged a ‘roundtable summit’ of Aboriginal leaders to address the issue of family violence. It turned out to be another stunt, with no follow through.

Aboriginal communities themselves, of course, had been crying for help for decades.

But for whatever reason, in 2006 the Australian media – and the Australian Government – suddenly found violence in Aboriginal communities compelling.

Maybe it was the fact that Nanette Rogers is a white woman, and Boni Robertson and Judy Atkinson are both black. But more likely, it was the way the stories were reported – with a level of sensationalism that rivals anything Today Tonight or A Current Affair have ever been able to cook up.

As the Nanette Rogers story bounced around the globe, Lateline decided it was time to turn things up a notch.

Night after night, Tony Jones and his team revisited the issue, filing 17 stories in just eight nights. As they did, the media frenzy around sexual violence in Aboriginal communities grew. So did the mainstream frustration, and the political posturing from elected leaders, who had known of the problems for decades, but done little to address them.

Six weeks into the frenzy, on June 21, Lateline dropped perhaps the most shocking revelations of them all.

The story, headlined ‘Sexual slavery reported in Indigenous community’, alleged that young Aboriginal children were being held against their will in Central Australia, and traded between communities as sex slaves. Some of the children were given petrol to sniff, in exchange for sex with senior Aboriginal men.

The story centred on the community of Mutitjulu, a tiny town of around 400 situated, literally, in the shadow of Uluru.

Lateline claimed senior men in the community had created an environment where a predatory paedophile was able to abuse women and children with impunity. The elderly man relied on his kinship connections for protection, claimed Lateline, and was one of the men trading petrol for sex with young children.

Media coverage had thus far been feverish, but with Lateline’s fresh ‘revelations’ it went into overdrive. And so did the Northern Territory government, which was bearing the brunt of critical media reporting. The Howard government – in office for more than a decade, and at the time responsible for the funding of remote Aboriginal communities – was escaping media scrutiny largely unscathed.

The morning after Lateline’s scoop, Northern Territory Chief Minister Clare Martin announced her government would hold a major inquiry into violence against children in Aboriginal communities.

The resulting report, Little Children Are Sacred, took almost a year to complete, ran to more than 300 pages, and contained 91 recommendations.

It was released publicly on June 15, six weeks after it was completed. The Howard government, which had sat on the Memmott report for 18 months, pounced.

On June 21, 2007 – less than a week after the public release of the report and a year to the day since the ‘sexual slavery’ story that sparked it – the Howard government accused the NT government of dragging the chain on child abuse. The feds would have to intervene.

And this is the point at where things really begin to fall apart.

Fake news

Lateline’s ‘sexual slavery in Mutitjulu’ story was a ruse almost from start to finish. While it contained broad aspects of truth – that Aboriginal people were desperately poor; that Central Australian communities suffered significant levels of violence and abuse; that women and children in particular were vulnerable – the story that went out on air was largely a fiction.

The story began with old file footage of Mutitjulu, and vision from other communities hundreds of kilometres away, which were passed off as being from Mutitjulu.

There was a simple reason for that. In the course of their major investigation into alleged sexual slavery in Mutitjulu, Lateline never once actually set foot in the community. What followed – the complete collapse of virtually every individual claim in Lateline’s story – was an almost inevitable consequence of that.

In its defence, Lateline has claimed it was denied entry into Mutitjulu by the community council – the very people who were the focus of Lateline’s allegations about protecting a predatory paedophile. That claim was later shot down by Parks Australia, managers of the National Park which surrounds Mutitjulu, when it revealed that Lateline’s “attempts” to visit Mutitjulu was in fact a single phone call inquiring about filming in the Kata Tjuta National Park, with no explanation of what they intended to film, and no subsequent formal request.

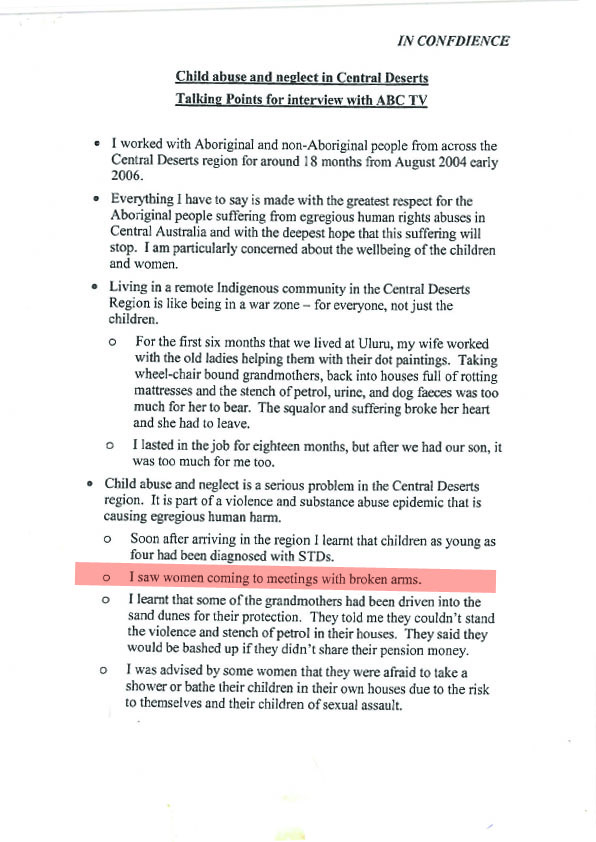

Lateline’s chief witness in the story was a man described as a ‘former youth worker’, who was once based in Mutitjulu and worked in a joint community development project for the NT and federal governments. He was interviewed at his new home on the outskirts of Canberra. In order to protect his identity, the man’s face was filmed in shadow and his voice was digitised.

There was, however, a number of holes in the cover story: the man was never a youth worker, and he had never lived in Mutitjulu.

He was Gregory Andrews, an Assistant Secretary in the Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination (OIPC), and the senior public servant who was advising Mal Brough specifically on violence and sexual abuse in remote Aboriginal communities, and in Mutitjulu in particular.

Lateline knew Andrews worked for the minister, and chose to deliberately lie about his real identity. The interview had originally been negotiated through the media unit of the OIPC, and he was to have appeared as ‘Gregory Andrews, government bureaucrat’ in the story.

For reasons that remain unknown o this day, Andrews instead appeared anonymously. And it’s that cover of anonymity – afforded by Lateline – that sent the story spinning out of control.

Andrews wept openly on camera as he described how he’d made repeated statements and reports to police about sexual violence perpetrated against Aboriginal women and children during his time in Mutitjulu. But, he claimed, he’d withdrawn those statements after being threatened by men in the community.

Despite moving several thousand kilometres away to Canberra, Andrews maintained that he feared for his safety, and that of his family.

Clare Martin later revealed in parliament that during his employment, Andrews never once made a single report to police about violence against women or children.

His ‘withdrawn police statements’ weren’t the only part of his story that collapsed.

As government documents now reveal, prior to his interview Andrews provided Mal Brough a ministerial brief on what he intended to say to Lateline as a government representative.

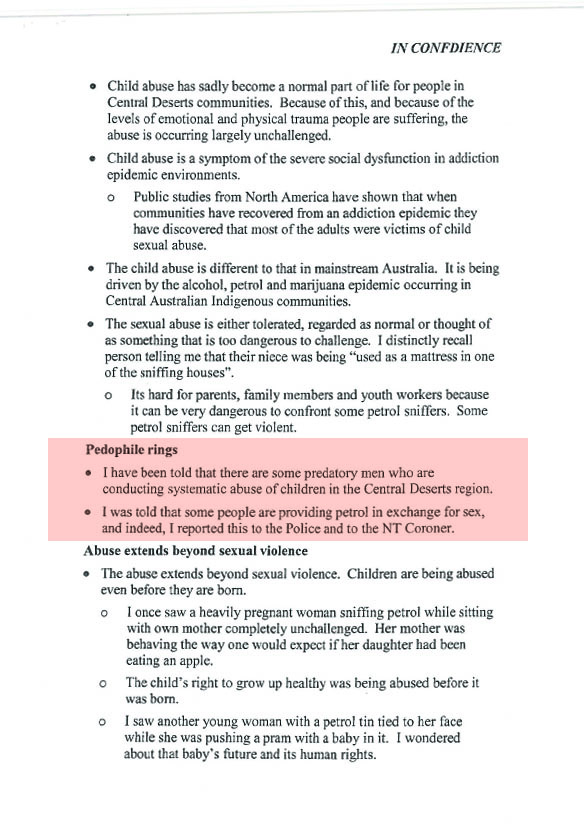

He told the Minister that he would tell Lateline there were predatory men in the central deserts region who were preying on children; that things were so bad in the community that he saw women coming to meetings with broken arms.

But when Andrews appeared on camera with his identity hidden, he got creative.

Andrews instead told Lateline this: “I saw women coming to meetings with broken arms, and with screwdrivers or other implements through their legs.”

And his claim that “there are predatory men in the central deserts who are systematically abusing young children” instead became this: “It’s true that there are predatory men in the central deserts who are systematically abusing young children. I’ve been told by a number of people of men in the region who go to other communities and get young girls and bring them back to their community and keep them there as sex slaves and… exchange sex for petrol with those young petrol sniffers.”

It’s spectacular stuff, and all of it since dismissed by the Northern Territory police, and the Australian Crime Commission, both of which conducted extensive investigations into the allegations.

It subsequently emerged that Andrews was prone to profound embellishment, even when his identity was known.

Just a few months before he appeared on Lateline an an ‘anonymous youth worker’, Andrews had grossly mislead a Senate Inquiry into Petrol Sniffing conducted a few months earlier telling parliament that life in Mutitjulu was so bad that “children were hanging themselves from the church steeple on Sundays and their mothers were having to cut them down”.

It never happened. Not once.

Andrews also told the inquiry that he lived in Mutitjulu for nine months. He never lived in Mutitjulu a single day. Most seriously, he misrepresented the findings of a coronial inquiry into a series of petrol sniffing deaths to federal parliament.

With the Labor Opposition circling, Andrews’ – now a senior federal government bureaucrat close to the Minister – was summonsed to appear before a Senate Estimates hearing, to explain himself. The government initially agreed he would appear, then changed its mind. Thus, Gregory Andrews became the first (and still only) bureaucrat in parliamentary history to avoid a Senate Estimates grilling on the grounds that he was “too stressed” to appear.

Even Godwin Grech, perpetrator of the ‘Utegate’ fraud that brought down Malcolm Turnbull’s leadership of the Liberal Party, plucked up the courage to front a Senate hearing.

With Andrews’ story collapsing, and questions on the floor of parliament about Lateline’s conduct, the ABC changed tack. It now claimed that the central interview in the report was not Andrews, after whose claims the headline was based. Instead, the central witness was a doctor who served in the Mutitjulu community for several years.

Dr Geoff Stewart had appeared only briefly in the story – for a matter of seconds. But after the story, he featured in a lengthy one-on-one interview with Jones. Dr Stewart also backed Lateline’s central claim – that men in the Mutitjulu community had created an environment where an elderly paedophile relied on family connections to abuse children with impunity.

Dr Stewart’s story would also fall apart. Spectacularly so.

The health records of the elderly alleged paedophile at the centre of the Lateline story were leaked to my colleagues and me at the National Indigenous Times. The revelations contained within them were staggering.

Dr Stewart had begun prescribing Viagra to the elderly man, aged in his late 60s, in September 2000. On several occasions, Dr Stewart documented concerns the man was misusing the drug.

In April 2001, months after first prescribing the drug, Dr Stewart wrote in the man’s health records: “Is using Viagra to have sex with young females”.

He continued to prescribe Viagra for another 10 months.

In February 2002, Dr Stewart finally cut the man off. Upon leaving the community for a new posting, Dr Stewart marked the front page of the man’s health record with a warning that he should not be given further prescriptions of Viagra.

Despite this, subsequent doctors who worked in the community ignored the warning and for at least another two years, continued to prescribe the drug to the man through the Mutitjulu Health Clinic.

To this day, there remains no evidence that the elderly man was actually targeting children. He was certainly in a sexual relationship with a younger woman, but she was aged in her late 20s. And there is certainly some question about the morals of the relationship – the woman was mentally impaired from years of petrol sniffing. But of course, consensual sex with an adult is not only not illegal, it’s not paedophilia.

Even so, that Dr Stewart prescribed Viagra while he believed the man was using it to target young females is extraordinary. But that he then appeared on a national current affairs program and blamed Aboriginal men in the community for creating the environment where an impotent old man was able to target young women beggars belief.

Lateline’s handling of that revelation, however, was even worse.

In the original story, Lateline revealed details of a leaked report to the Northern Territory government which, viewers were told, backed the central theme of Lateline’s claims – that powerful Mutitjulu men were protecting the elderly paedophile.

What Lateline declined to disclose is that the report also alleged that doctors in Mutitjulu were prescribing Viagra to the man, against the wishes of the local community.

Why Lateline chose to keep this information secret, and why it chose to give the very doctor who was doing it air-time to blame black men for the alleged abuse, remains unanswered.

Unfortunately, the problems with Lateline’s reporting went beyond its two chief witnesses.

Blame it on the ‘blacks’

Kumuntjay Randall was a respected Aboriginal film-maker and the writer of Brown Skin Baby, an anthem of the Stolen Generations. He passed away several years ago, but was running the Mutitjulu Health Clinic during Dr Stewart’s reign.

Lateline directly accused Mr Randall of harbouring the elderly alleged paedophile, and of protecting other violent men.

In the lead up to Lateline’s 2006 story, Mr Randall was touring the nation promoting Kanyini, a film about his life. He was approached by Lateline for an interview about the film, but once on camera he was ambushed with the allegations about Mutitjulu.

It was the kind of ‘foot in the door’ reporting that you might expect from commercial television. It also happens to be a clear breach of both the Journalist Code of Ethics, and ABC policy.

Lesley Calma, Randall’s nephew, was also targeted in the story. Lateline reported that he had “two convictions for assaulting a female”. What Lateline did not disclose to viewers is that the convictions were around four decades old. It’s an offence in the NT to publicly disclose a spent conviction (more than 10 years old).

Finally, it later emerged that the old man at the centre of Lateline’s story had actually been forced out of the community more than half a year before the program aired, because of his behavior towards women.

The whole premise of the story – that Mutitjulu men had protected this alleged paedophile – collapsed.

Yet days after it’s original report, Lateline followed up with a story inferring the man had fled the community “recently” as a result of their reporting.

With the comfort of the media

Tony Jones was right to correct Dave Tollner. The Northern Territory intervention was a policy launched by a government, not by the ABC.

But the Howard government could never have enacted legislation described by the United Nations as “unique” and “striking” in its racism, without the comfort and cooperation of Australia’s media.

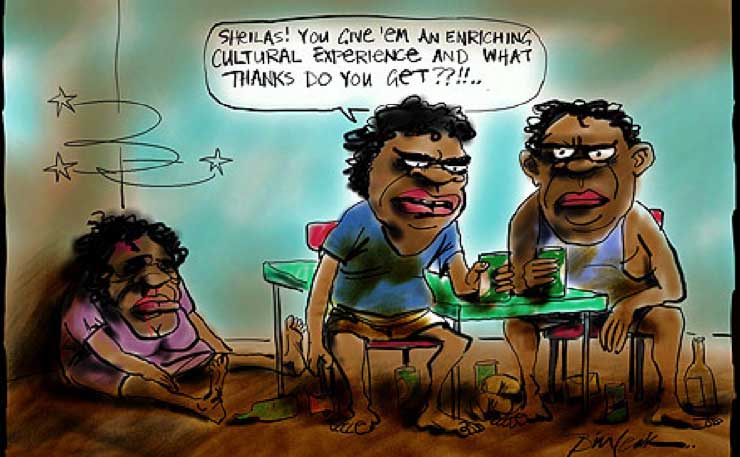

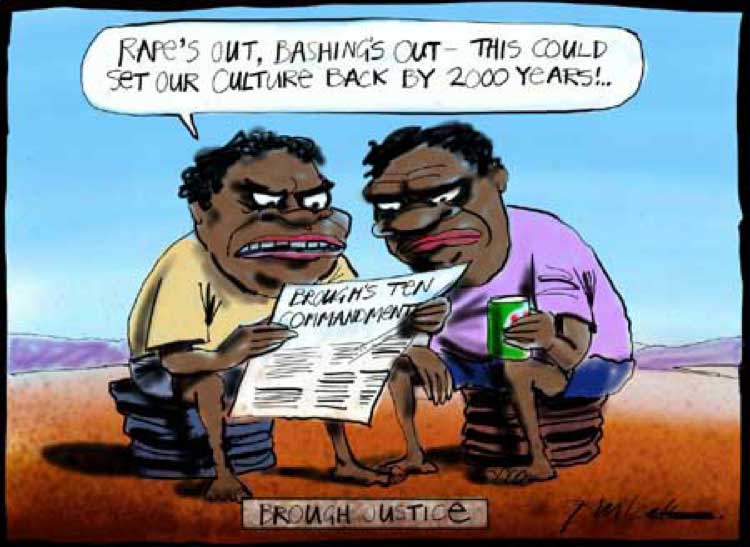

While the mainstream media in large part came along for the ride – these cartoons by Bill Leak appeared in The Australian at the time – Lateline was the Howard government’s chief ally.

To this day, however, Jones, Suzanne Smith (the journalist who filed the story), Brett Evans (producer of the story) and the ABC more broadly have never accepted any responsibility.

Not for the intervention that came about as a direct result of their reporting, and not for the atrocious reporting itself. Instead, they’ve maintained the fiction that Lateline’s reporting was ‘journalism at its best’.

If Lateline’s coverage of ‘sexual slavery’ in Central Australia is the best journalism the ABC can deliver, then it’s frightening to think what their worst looks like. And it’s terrifying to think how the ABC would confront ‘its worst’ journalism, given how it dealt with ‘its best’.

After the Lateline story aired, the Mutitjulu community submitted a lengthy complaint to the ABC. It was referred to the ABC Complaints Review Panel, an instrument described by the ABC as “independent” despite the fact it was appointed and funded by the ABC.

Having thoroughly investigated itself, the ABC found that it had done nothing wrong, save for the minor oversight of failing to label vision from communities other than Mutitjulu as file footage.

That’s it. The sum total of the ABC’s findings.

It had no problem with the fact Lateline faked the identity of its chief witness. This was done to protect Andrews’ identity, found the ABC, ignoring the fact that not only was Andrews originally willing to appear as Andrews, but that shortly after filming the interview he spent several days in the Mutitjulu community on behalf of the Howard government without protection, and without incident.

The ABC also found no fault with the ambush journalism employed against Mr Randall, nor the fact Leslie Calma’s criminal record was grossly misrepresented.

It had no problem with the fact Lateline never even visited Mutitjulu, and never disclosed this fact to viewers.

But what is most concerning is that the ABC had no problem with Lateline’s refusal to report almost all of the revelations that emerged as their story very publicly fell apart.

The allegations that children were being held as “sex slaves” and traded between Aboriginal communities sparked major police investigations, including an extensive inquiry by the Australian Crime Commission. The ACC – which enjoyed star chamber powers for the investigation – found no evidence of paedophile rings in Mutitjulu, nor Central Australia more broadly.

The specific claims by Lateline that petrol was being exchanged for sex with children in Mutitjulu, also sparked a major investigation by Northern Territory police. According to the federal government, up to 300 people were interviewed by police.

A month after Lateline’s story, NT police Superintendent Colleen Gwynne subsequently staged a press conference to reveal the details of the police investigation.

“We have found some evidence of petrol being provided to children,” Supt Gwynne said. “We haven’t found any evidence of petrol being provided for sexual favours. There’s certainly no evidence there that the petrol is being provided to entice children to provide sexual favours, none whatsoever.

“There’s still no direct evidence that identifies anyone who has sexually abused any children in central Australia,” she said. “There’s a lot of hearsay, ‘This is what we were told, someone else told me this’. You go from one person to another and then you finally get someone and they say ‘That’s not what I said’.”

Lateline refused to report Superintendent Gwynne’s statements, later claiming that it didn’t have the space to run the story. It must surely be the first time in Australian media history where an outlet breaks a story that sparks a major police inquiry, and then refuses to report on the results of that police inquiry.

Lateline did, however, find space to run a story headlined ‘Indigenous community expresses thanks for exposing child abuse’ a self-congratulatory puff piece that quoted a non-Aboriginal woman from Yuendumu, a community some 12 hours drive from Mutitjulu, and not featured in the original story. That woman – Pamela Malden – has since been jailed for large-scale fraud committed against the Yuendumu Women’s Centre.

As for the revelations that the other chief witness in the Lateline story – Dr Geoff Stewart – had prescribed Viagra to the alleged paedophile up to 10 months after expressing concern he was using the drug to target young females, as you can probably imagine, the story got a healthy run in mainstream media. It did, after all, feature paedophiles, blackfellas and Viagra – a ‘made for mainstream media’ yarn.

To this day, there remains only one major news organisation in the country that has refused to report the story.

Despite the story breaking nationally, not one ABC outlet in the country – no radio station, no TV program, no online forum – ran a single syllable of the revelations.

Journalists in ABC Darwin’s newsroom later complained they’d been prevented covering the collapse of Lateline’s story by management. And for the record, to this day, ABC’s Media Watch program has still never uttered one word about the entire issue.

Who will think of the children?

Dysfunction and poverty in Aboriginal communities is confronting, and heart-breaking.

But therein lies one of the great dangers in Aboriginal affairs policy-making, and media reporting – a belief that sometimes the ends do really justify the means, and that things are so bad in Aboriginal Australia that basic media ethics and standards can be suspended.

It’s thinking that comes from the ‘at least we’re doing something’ school of government policy, a belief that action – any action – is better than what we’ve collectively been doing, which is less than the bare minimum. But what if ‘what we’re doing’ is making things worse?

The Little Children Are Sacred report noted, “ … It is a very important point and one which we have made during the course of many of our public discussions of the issues that the problems do not just relate to Aboriginal communities. The number of perpetrators is small and there are some communities, it must be thought, where there are no problems at all. Accepting this to be the case, it is hardly surprising that representatives of communities, and the men in particular, have been unhappy (to say the least) at the media coverage of the whole of the issue.”

For obvious reasons, that ‘unhappiness’ is particularly acute in Mutitjulu, where local elders say their community has virtually emptied since the program.

“They just couldn’t stand the shame of the way they were all cast as paedophiles and abusers,” said Mr Randall, before his passing.

It’s an unhappiness that is also palpable across the rest of the Northern Territory. A subsequent federal government review of the NT intervention found that incidents of attempted suicide and self-harm in Aboriginal communities had more than quadrupled in communities since the launch of the NT intervention.

It’s not hard to imagine the public response if a government policy had achieved the same result in a non-Aboriginal community.

More broadly, school attendance rates across NT intervention communities have actually dropped, down across the board on pre-intervention numbers.

At the same time, starvation rates and anaemia rates spiked immediately after the intervention was launched, and reports of alcohol-related violence more than doubled.

The federal government review conceded that child neglect is a much bigger problem than abuse in remote communities, which is hardly surprising if you understand the grinding poverty that is the daily reality of Aboriginal life in the Territory.

The review reported 272 referrals for child neglect to welfare agencies in 2010-2011, up from 100 at the start of the intervention.

That neglect is getting worse under the NT intervention surprises no-one who is aware of the policy, and its impact on the ground. But that Aboriginal mothers and fathers are being blamed for it, while their own needs have been neglected by government for decades, is simply staggering.

As for child sexual assault, the report found the number of convictions remained steady at around 11 per year – the same figure from the start of the intervention.

The report notes: “The number of convictions for child sexual assaults committed in the NTER communities in 2006-07 was 11. In 2007-08 it was 10, in 2008-09 it was 11 and in 2009-10 it was 12. The total number of child sexual assault convictions over the period 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2010 is 33.”

Curiously, it adds: “The conviction rate for child sexual abuse is likely to understate the actual level of abuse and it is misleading to view it in isolation.”

No explanation why, but a remarkable concession none-the-less. Wasn’t the whole point of the NT intervention – the ‘national emergency’ that required the suspension of the Racial Discrimination Act and the intervention of the army – designed to expose the abuse and catch the perpetrators? And wasn’t that the point of Lateline’s reporting?

A decade on, and billions of taxpayer dollars later, we’re supposed to accept that it’s all made no impact at all? And that in key areas like education, health and violence, things have actually gotten worse.

And that’s the central point of this story: Lateline’s style of reporting might get attention, but it does not fix problems.

Nor does the sorts of government policies that were made possible in an environment of media sensationalism and the demonisation of the nation’s most disadvantaged people.

Bad things may happen when good people stay silent, but the sad reality of Aboriginal affairs is that really bad things can happen when good people speak up.

Sexual abuse is undoubtedly a problem in Aboriginal communities – no-one ever really denies that, despite the vulgar attempts of Lateline and others to portray those who question their methods as supporters of paedophilia.

It’s also clear that sexual abuse occurs at higher rates in some Aboriginal communities than the national average. There are many reasons for this, overcrowding being chief among them.

If you have, as is the case across the Territory, more than a dozen people living in a single dwelling (upwards of 30 is not uncommon) then the introduction of a single sexual predator to a household provides access to substantially more victims.

The intervention response to this fact was to promise new housing. Michael Brull, writing for ABC’s The Drum, linked several government reports, with devastating and humiliating results.

The average occupancy rate of Aboriginal homes in the Territory prior to the NT intervention was 9.4, reported Brull. The target post-intervention is 9.3. This despite expenditure on the NT intervention’s housing program of around $700 million.

This was the same intervention housing policy which somehow managed to expend more than $120 million in its first two years of operation, without ever actually building a single Aboriginal home.

In short, the whole policy – housing, education, you name it – has been a spectacular failure. It has made things worse. And yet successive governments – Labor and Liberal – have supported it. The Coalition conceived the intervention, and it passed throughout parliament with Labor’s support. Labor then extended it for a decade in 2012, through the ironically named Stronger Futures legislation.

Problems in Aboriginal communities in the Territory and beyond are complex and entrenched. They required a considered and calm response.

And as the Little Children Are Sacred Report noted in its first recommendation, what Aboriginal Territorians – among the nation’s most vulnerable people – need above all else is government policy made with the cooperation and consultation of Aboriginal people themselves.

What they got instead was bad government policy made with the cooperation of mainstream media who were more interested in sensationalism parading as serious journalism.

That our national broadcaster led the charge is a matter of enduring shame for the ABC.

The last word belongs to Lateline.

In the original interview with Nanette Rogers, Tony Jones asked, “Given what’s in your paper and what you’ve told us here tonight, are you worried that the information itself may be abused by tabloids and racists even, shock jocks – the sort of people who will take information like this and exploit it?”

‘Yes,” answered Rogers.

POSTSCRIPT: Where are they now?

By way of update (2017), it’s worth considering where the various characters in this story ended up.

Tony Jones went on to host the popular Q&A program. He continues to defend the reporting, and did so here in 2006 on Crikey.

Suzanne Smith (pictured above) the journalist who crafted the Lateline story, was never sanctioned for her reporting. She was enjoyed several roles and promotions within the ABC since, including as the Executive Producer of the ABC’s online investigations unit, and is now serving as a senior journalist with Foreign Correspondent.

Brett Evans, the producer of the story, was eventually promoted to Acting Executive Producer of ABC’s Media Watch program. He has since left the ABC.

Amid the controversy, Gregory Andrews, the ‘anonymous youth worker’ – took leave without pay from the Australian Public Service. He worked as CEO for the government-funded Indigenous Community Volunteers. In 2014, Andrews was announced as the Abbott Government’s new ‘Threatened Species Commissioner’. The ABC reported on the appointment critically, however neglected to mention any of the details of his involvement with Lateline.

Dr Geoff Stewart – who prescribed Viagra to the elderly alleged predator then blamed the community for the problems – went on to work as the Senior Medical Officer for the Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance of the Northern Territory (AMSANT). He still works as a doctor in remote communities in the Northern Territory.

Mal Brough (pictured above) lost his seat in the 2007 election, but returned to parliament in 2013, after winning former speaker Peter Slipper’s seat, despite being slammed by the Federal Court for his involvement in the Slipper affair.

Brough was included in the first Turnbull ministry, after backing Turnbull’s coup against Tony Abbott. He was forced to resign months later, however, amid a federal police investigation over his alleged conduct in relation to the slipper affair.

John Howard, was, of course, annihilated at the election immediately following the launch of the NT intervention. His party was cast from office, and he became only the second Prime Minister in history to lose his seat while still in office. Subsequent reporting by News Corporation revealed that 24 hours before Howard and Brough announced the intervention, Howard was handed a report by his party’s chief pollsters, Mark Textor and Linton Crosby, which recommended the Howard government be seen to ‘intervene’ in the affairs of state and territory governments (all of which were held by Labor) in order to make the federal Liberals look strong, and Labor incompetent.

ABC Lateline won a Logie for its series on Central Australia.

The ABC more broadly now actively resists attempts to revisit the story. It refuses to provide an video or audio of the programs in dispute, and a Freedom of Information request lodged in 2012 resulted in the ABC providing a single document for scrutiny, one which had no real relevance to the issue.

The complaints review panel process which exonerated Lateline was subsequently abolished. The actual complaint review finding has been removed from the ABC’s website.

The outcomes for Aboriginal people involved in this story were vastly different.

Government whistleblower, Tjanara Goreng Goreng.

Tjanara Goreng Goreng (pictured above), an Aboriginal woman who worked alongside Gregory Andrews and became a central whistleblower in the story, had her home raided by Australian Federal Police. She was subsequently prosecuted and convicted for releasing Commonwealth information, and bankrupted as a result of a substantial legal bill.

Kumuntjay Randall – accused by Lateline of covering up paedophilia died in 2015. He never received an apology from the ABC, and told John Pilger in his 2014 film Utopia* that his community had not recovered from the ABC’s reporting.

Mr Randall’s daughter, Dorothea Randall, and another Aboriginal man from Mutitjulu also had their homes raided by the Australian Federal Police.

Leslie Calma continues to reside in Central Australia, and has never received an apology nor any acknowledgement from the ABC over the misreporting.

The community of Mutitjulu had its funding stripped and services closed down by the federal government, however this was restored after a win in the Federal Court by Sydney lawyer George Newhouse.

* The revelations in this story were uncovered by the author, Brian Johnstone and Amy McQuire, as part of the investigative team at the National Indigenous Times.

** Chris Graham worked as an Associate Producer on John Pilger’s film Utopia.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.