2016 marks the end of the post-war liberal consensus, writes Ben Eltham.

Are you sick of the hot takes yet? Of course you are. If there is one thing the election of Donald Trump has proved, it is the human need for rationalisation. When faced by a powerful yet unexpected event, we humans seek to make sense of it. To place it in context. To explain it in terms that allay our fears, and help our understanding.

And so the hot takes have washed over us, as the world has reacted to the astonishing US election result of November 9, in never-ending waves of half-baked analysis.

Name your poison: there’s an easy explanation in hundreds of different flavours. It was Hillary Clinton’s fault (too many to link to). It was the White Working Class, a demographic we formerly neglected, but that now deserves its own three-letter acronym. It was the triumph of authoritarian appeal. Or Trump’s mastery of the new media environment. Or it was the revenge of a forgotten America, angry at the way they had been left behind by cosmopolitan elites. Or was it the end of Obama’s legacy? The beginning of fascism? The triumph of fear over love?

There is a grain of truth in all of these analyses, but none seem really satisfying. So let’s examine some of the facts that we do know.

Clinton won the popular vote. This makes her only the fourth candidate in history to win a majority of votes, but lose the electoral college. This is always a possibility in a system like America’s, where the president is chosen on a state by state basis. And, to be fair to the Americans, it can also happen here: Labor won more votes than the Coalition in 1998, but John Howard’s Liberals won the seats that mattered.

Clinton’s lead in the popular vote is significant. It is likely to be in the millions, once all the votes are counted. That’s a pretty big deal. She may well win the popular vote by more than one per cent: the largest popular margin for a losing candidate since 1888.

In other words, Donald Trump does not have a popular mandate. He owes his victory first and foremost to the electoral college.

Another point worth making is that Clinton lost by an agonisingly small margin. Analysis by the Washington Post concludes that the electoral college was lost by a margin of just 107,000 votes in three states. Things could easily have swung Clinton’s way. Well into the evening, neither the Republicans nor Trump’s own camp thought that he would get over the line. Only when the results started to go his way in Michigan did it become clear that Trump would triumph.

One of the key factors appears to be low voter turn-out, especially for Clinton. Particularly in the mid-west, fewer voters turned out to vote for her than voted for Obama in 2008 and 2012. This might have made the difference in Pennsylvania. As Michael Brull pointed yesterday in a fine article here at New Matilda, “part of the election is about how Trump won voters, but a bigger part has to account for Clinton’s loss of so many longstanding voters.”

That is little solace to Clinton and the Democratic establishment. Nor will it halt the outpouring of grief and anger from liberals and the left.

Clinton led in opinion polls by wide margins for much of 2016. While it’s now clear that the polls understated Trump’s vote, it’s also clear Clinton enjoyed big leads for long periods. How was Trump allowed to get within striking distance? How did Clinton manage to run such a poor campaign? Why were states like Florida and North Carolina targeted, while the mid-west and Great Lakes were ignored? Everybody now has an opinion, or several opinions, and the Monday-morning quarterbacks are lining up to pronounce their diagnoses.

There is certainly a racist element in Trump’s election. How could there not be, given all of the things he has said and promised? Trump’s open embrace of anti-immigrant views were overtly tinged with racial language. This matters.

Substantively, Trump’s exit polling figures among whites were far better than for Mitt Romney four years ago, and his electoral college victory was ultimately because he was able to win formerly Democratic states in the mid-west – states that he won by winning demographics that are predominantly white.

But racism can’t be all of it. Clinton failed to entice as many minority voters as Obama in a range of key states. Clinton did worse than Obama four years ago in a range of demographics, including, almost unbelievably, amongst Latinos.

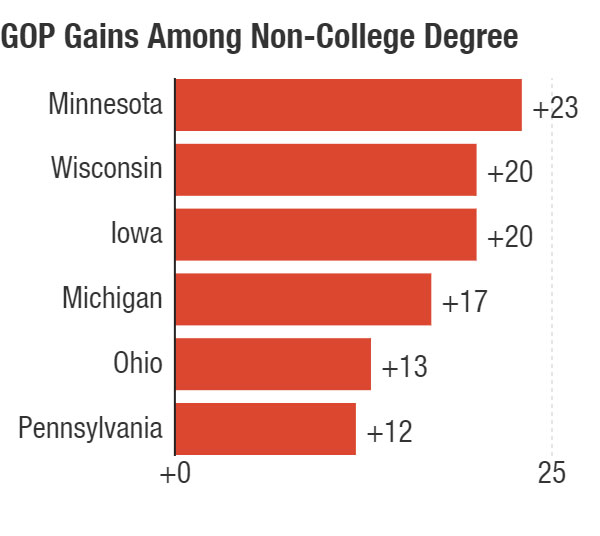

In fact, the biggest predictor of the election result was not race at all. It was education. Clinton won handsomely with university graduates. But she suffered disastrously when it came to voters without degrees, especially in the industrial north. In Minnesota, Trump won amongst voters without college degrees by 55-38 per cent, a gain of 23 points from Romney’s performance in 2012. In Wisconsin it was 56-40, a swing of 20 points; in Michigan 49-45, a swing of 17 points; in Pennsylvania 52-45, a swing of 12 points.

WHAT were these voters reacting to? On some level, surely, race. There is no point denying it. We should accept that race played a key role in Donald Trump’s election. Just as surely, gender played a part too.

But on another level, it must be partly true that voters favoured Trump’s positive economic message of restoring trade barriers, investing in infrastructure, and rebuilding America’s industrial base. This was indeed the prediction of filmmaker Michael Moore, and it was echoed by plenty of anecdotal evidence from reporters who got out from behind their computer screens and travelled extensively in the American heartland.

The ABC’s Zoe Daniel took a trip through western Pennsylvania in late October. She couldn’t find a single Clinton supporter. Guy Rundle also found plenty of support for Trump in the post-industrial mid-west. He wrote last week of “the story that I’ve been seeing on the road, and which aren’t borne out in the general stats — that recovery is uneven, non-existent in many parts of the country, and the appeal of Trump is that ‘he can sort things out because he’s a businessman’, a phrase I’ve heard a hundred times, in innumerable variations.”

Matthias Kolb from the Süddeutsche Zeitung talked to voters in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania’s capital. “They feel Trump is the guy who will work for them,” he told the Atlantic in July. On November 9, Pennsylvania flipped the state’s 20 electoral college votes to Trump.

The New Yorker sent lauded essayist and short-story writer George Saunders out into Trumpland. In July, Saunders filed a long essay, since updated. In characteristically knotty and perceptive prose, Saunders teased out a patch-work quilt of disaffection and grievance, united by a vague but powerful feeling of cultural decline.

“The Trump supporters I spoke with were friendly, generous with their time, flattered to be asked their opinion, willing to give it, even when they knew I was a liberal writer likely to throw them under the bus,” Saunders wrote.

They loved their country, seemed genuinely panicked at its perceived demise, felt urgently that we were, right now, in the process of losing something precious. They were, generally, in favor of order and had a propensity toward the broadly normative, a certain squareness … The Trump supporter comes out of the conservative tradition but is not a traditional conservative. He is less patient: something is bothering him and he wants it stopped now, by any means necessary. He seems less influenced by Goldwater and Reagan than by Fox News and reality TV, his understanding of history recent and selective; he is less religiously grounded and more willing, in his acceptance of Trump’s racist and misogynist excesses, to (let’s say) forgo the niceties.

Perhaps the best grass-roots reporting of the 2016 election has been done by the Guardian’s Chris Arnade, who spent the best part of a year travelling through the heartland and talking to ordinary voters. Arnade’s reports of an angry and humiliated America are worth reading in full, but a flavour of his work can be gathered by this essay published the week before the election, in which he distilled some of this thoughts.

Arnade underlined the themes of a divided America, riven by class, culture and education.

Most of all, Trump voters want respect. They want respect for their long hours of work that risks their bodies, for the hands caught in vices, backs wrenched by weights, and knees torn. They want respect because they are doing dangerous work, but their pay has been flat for decades. They want respect because they haven’t just lost economically, but also socially. When they turn on the TV, they see their way of life being mocked and made fun of as nothing but uneducated white trash.

As the exit polls suggest, a key dividing line was education. Arnade writes that the gap between Americans with tertiary education and those with a little high school is now so great that the two classes barely interact with one another.

As months went by, Trump wasn’t just exploiting and expanding white racism; he was also exposing a divide between those with good education, and those without. A version of the school room front row kids versus back row kids.

It became simple: if I wanted to talk to a community overwhelmingly supporting Trump, I would go to a white town or neighbourhood nearest the rusting factory surrounded by razor fence.

If I wanted to find Clinton, or Jeb Bush, or even Rubio voters, I would go near a university, or go to the wealthier neighborhoods near tech companies, or near headquarters of global corporations.

But few media organisations had the resources to send a Chris Arnade into the field for a year. Even those that did, like the Guardian, largely ignored his predictions.

The media excoriated itself for missing the obvious, for so uniformly dismissing Trump, even while giving him blanket coverage, and for writing off his chances, even while devoting more attention to his campaign and persona than any single policy issue. The pollsters had also got it wrong, so there were attacks on polling too – especially the celebrity pollsters like Nate Silver, who had so irritated many by being right so often in the past.

And because many could not credit the result for what it was, there was an outbreak of democracy bashing, as many attacked the institution that facilitated Trump’s victory.

Perhaps it was the fault of the electoral college. Or perhaps the voters themselves were to blame. The cacophony of despair reached its crescendo with an article by Giles Fraser, also in the Guardian, which surely takes the cake for the single worst analysis of the entire lot. “This US election result is a terrific argument for monarchy,” Fraser wrote.

And so the hot takes continued, getting gradually sillier.

The media is certainly culpable. Just as we can’t deny race, we can’t deny the media’s role either. Trump was seized upon early as the most mediagenic element by far of the presidential campaign, and he dominated news media channels, particularly Fox News, virtually from the beginning of the Republican primaries. Trump masterfully manipulated his celebrity to effortlessly gather months of blanket cable television coverage.

But the institutional media did eventually get around to training serious attention on Donald Trump’s policies and fitness for office. The mainstream media spent plenty of time reporting on Donald Trump’s checkered business past, his mercurial character, and his decidedly irregular finances. He was shown to be a sexual abuser, a liar, a business failure, a tax avoider, a real estate shyster and a racist. In 1996 or even in 2004, this might have been the decisive factor in killing off his primary race, long before he got anywhere near the Oval Office (which he has now visited, meeting Barack Obama).

It didn’t matter. In 2016, the US mediascape has fragmented beyond recognition, such that the anti-Trump hostility of liberal media organisations such as the New York Times and the non-Fox television networks made little difference. The long-held assumption that opposition, or even ridicule, from powerful television networks and newspapers would torpedo a presidential candidate’s chances has been shown to be baseless: as baseless as Hillary Clinton’s much vaunted ‘ground game’.

The world has changed. Our increasingly digitalised and mediated lives are splintered and narrowcast. Vast swathes of the American population get their news almost solely from fly-by-night partisan news outfits churning clickbait through the social media networks, especially Facebook.

Exhibit A in the trend is Breitbart News. A fringe player just a year ago, the far-right online conspiracy factory has now vaulted Steve Bannon all the way to the top, as one of President-elect Trump’s top strategic advisors.

Breitbart News is openly sexist, white supremacist and conspiratorial. As the New Yorker’s Ryan Lizza argues, the elevation of Bannon to Trump’s key advisor is an “epochal event in American politics.” Bannon frankly identifies with the far-right, including European models such as Marine Le Pen and Nigel Farage. Having someone of his ilk in the White House administration marks a step-change in American conservatism. It is impossible to imagine such a figure in a senior role in George W. Bush’s White House, or Ronald Reagan’s. James Baker, ‘Scooter’ Libby, Andrew Card and Karl Rove were all committed conservatives, but they were also establishment figures with long records in public administration or as Republican campaigners.

Some of the best information we have about Bannon’s relationship with Trump comes from a series of one-on-one radio interviews between the two on Bannon’s radio show on Breitbart News Daily, a radio show on SiriusFM’s “Patriot” channel.

That Trump’s top advisor could be a former boss of Breitbart is perhaps the most graphic example of the polarisation of political discourse in the United States, where voters of different political inclination are now increasingly living in different epistemic worlds.

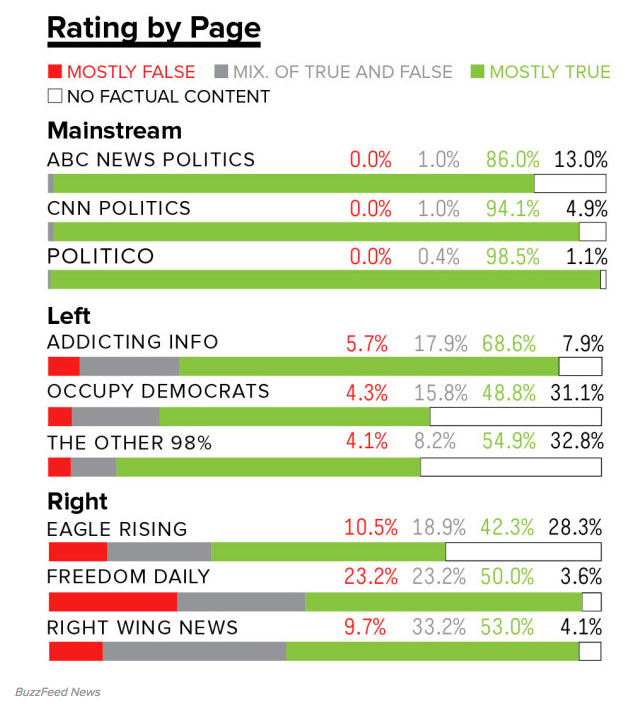

What does it mean that 44 per cent of Americans get their news from Facebook? One of the things it means is that bespoke falsehoods have become part of the wallpaper of everyday digital lives. More than a million people shared a fake story claiming that Pope Francis has endorsed Trump. Millions more shared a story about a fake quote attributed to Trump from the 1990s, pretending to quote Trump in People magazine saying that “If I were to run, I’d run as a Republican. They’re the dumbest group of voters in the country.” That story, too, was false.

Many of my friends have shared the fake Trump quote with me on Facebook. I don’t blame them: it seemed plausible; it was just the sort of thing Trump could have said. And in the sharable world of online content, links and memes and factoids all seem alike. An authoritative report from the New York Times looks remarkably similar to a trashy factoid confected by a group of teenagers in Macedonia.

As John Herman wrote in the New York Times this August,

These are news sources that essentially do not exist outside of Facebook, and you’ve probably never heard of them. They have names like Occupy Democrats; The Angry Patriot; US Chronicle; Addicting Info; RightAlerts; Being Liberal; Opposing Views; Fed-Up Americans; American News; and hundreds more. Some of these pages have millions of followers; many have hundreds of thousands.

In October, a BuzzFeed investigation showed how this cluster of hyperpartisan alt-right clickbait factories was able to push thousands of fake articles onto the Facebook platform to audiences in the millions. BuzzFeed claimed 38 per cent of them were mostly or partly false. In the final months of the election campaign, fake news items were shared more commonly than real ones.

Facebook is beginning to resemble a public sphere version of Gresham’s Law, with bad information driving out the good. Just to take one example: a team of epidemiologists examined the spread of information about Zika virus on Facebook this year. They found that inaccurate posts were more widely spread than accurate ones. This misled the public on important public health information.

The dark recesses of the alt-right hatesphere are just one manifestation of a fragmenting media environment that appears to be changing some of the fundamentals of politics itself. As Jill Lepore pointed out in a prescient essay early in the primary season, political parties are as much creations of the media as they are representatives of political interests: “the American two-party system is a creation of the press.” Rapid change in the media can have destabilising effects on the political system, as historians and philosophers from Alexis de Tocqueville to Jurgen Habermas have argued.

The increasingly fake nature of news shard on Facebook has started a genuine debate about the social network’s influence on democracy. Mark Zuckerberg even posted about it, musing in a Facebook post that:

Identifying the ‘truth’ is complicated. While some hoaxes can be completely debunked, a greater amount of content, including from mainstream sources, often gets the basic idea right but some details wrong or omitted. An even greater volume of stories express an opinion that many will disagree with and flag as incorrect even when factual. I am confident we can find ways for our community to tell us what content is most meaningful, but I believe we must be extremely cautious about becoming arbiters of truth ourselves.

Zuckerberg maintained that Facebook had not influenced the election. “Overall, this makes it extremely unlikely hoaxes changed the outcome of this election in one direction or the other.”

But this barely begins to address the influence of Facebook on the modern political landscape. The social network is the dominant force in the increasingly digitalised and machine-sorted opinionscape that has come to be known simply as the “filter bubble.” We live in the age of the media algorithm.

By its very design, the Facebook algorithm sorts our online lives into bubbles of like-minded opinion and thought. As Mostafa El-Bermawy puts it, “the social bubbles that Facebook and Google have designed for us are shaping the reality of your America. We only see and hear what we like.” Facebook’s own research confirms the theory. The company has already carried out experiments on the news feeds of its users, and presumably tinkers with the algorithm in small and unannounced ways continually. The point of all this is to sell online ads, from which Facebook makes billions of dollars.

In a widely-read essay earlier this year, the Guardian’s managing editor Katharine Viner wrote a scathing critique of the bubble’s influence on the contemporary media. “Asking technology companies to ‘do something’ about the filter bubble presumes that this is a problem that can be easily fixed,” she wrote, “rather than one baked into the very idea of social networks that are designed to give you what you and your friends want to see.”

Viner’s warnings are all the more convincing because the Guardian is an enthusiastic Facebook publisher, adopting the platform early and pushing its content on the social network assiduously. Despite this, the Guardian and its governing trust are losing money. The newspaper has just announced it is shedding more staff.

In commercial terms, Facebook is eating the news media alive, rapidly monopolising the means of distribution of online news. The platform has become so dominant that in 2015 a group of nine major online news publishers signed publishing deals with Facebook. The deal pushed their content directly onto the Facebook front end. The deal included such bastions of the traditional news business as NBC, the New York Times, the Atlantic, the Guardian, the BBC and Spiegel Online. Facebook is the single largest source of traffic to news sites.

The rise of social media asks urgent questions of citizens and governments, if we are to safeguard the future of our democracies. Where the environment for public discourse is being gamed and corrupted, serious thought must be given to regulating what has become a dangerous media monopoly. In its pomp, old media was immensely powerful in the conduct and outcome of elections. But old media companies were also governed by a set of black letter laws and unwritten conventions that imposed some residual restraints on their political agency. New fetters must now be fashioned for the increasingly powerful new media.

JUST as the election result can’t just be put down to racism, it can’t solely be attributed to the corruption of Facebook.

The Trump ascendency is overtly political, and can only be understood by careful social, economic and political analysis. It is foolish to deny that the Trump victory has been fuelled by long-term and deep-seated social trends that are affecting the composition of western post-industrial democracies.

The key term is ‘post-industrial’, as the Trump whitelash is surely as economic as it is racist. The states that flipped to Trump were most tellingly the rust belt mid-west, where jobs have departed with the flight of heavy industry and manufacturing, and where industrial blight has been followed rapidly by social breakdown.

The litany of problems of deindustrialised America is all too familiar: family breakdown, crime, an epidemic of addiction, widespread depression and rising mortality. Diagnoses of the plight of the poor white class have become something of a cottage industry, with breakout success for authors like J.D. Vance for his memoir Hillbilly Elegy and Nancy Isenberg for her class history, White Trash.

It’s telling that many Trump voters were not amongst the poorest Americans: these still voted for Clinton, where they did vote. Trump’s support base appears to subsist a little higher up: in the lower rungs of the shrinking American middle class. The United States, with its threadbare social safety net, imposes economic insecurities on the middling strata of its society far in excess of most other rich nations. Insecurity abets fear. Many Americans are just one redundancy or major illness away from bankruptcy. It’s not surprising that such insecurity goes hand in hand with a more general feeling of national decline.

But for all the economic explanations, there is no doubt that the rise of the populist right in the United States, Britain and Europe is a symptom of a much wider cultural anxiety. Yes, that anxiety is racial, and gendered. But it is also moral, as whole communities of voters reject the social liberalism of gay rights, feminism, gender equality and hedonistic atheism.

There are surely psychological reasons underpinning the strength of the populist right in recent times. Moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s research reminds us that politics has always been emotional as well as rational, and that fear, anger and disgust can prove powerful motivators for citizens registering their disaffection.

The laments of journalists and progressives about fake news and self-selecting filter bubbles are really just a microcosm of a much bigger problem. Liberalism itself has run aground. More and more voters in western democracies are rejecting liberal ideas.

As soon as you start throwing words like “liberalism” around, it’s easy to get bogged down in terminology. So let’s talk specifics. Clinton’s platform was a perfect encapsulation of the late modern project of liberalism.

Clinton is socially liberal: embracing the tolerant position on social issues like feminism, abortion, gay rights and racial equality. She championed diversity, education and human rights. But she is also economically liberal (or, in the fashionable word we use today, neoliberal), pushing free trade, open borders, high-tech industries, and an open and unfettered knowledge-based economy.

It’s not surprising that many saw Clinton as an avatar of the establishment. She is, after all, a paid-up member of the establishment. As a key member of the Obama and Clinton administrations, a Senator from New York and a Secretary of State, she is, by definition, a member of the ruling elite.

Clinton was also very pro-Wall Street. For reasons of fundraising and through the Clinton Foundation, Clinton was in fact very close to the US banking establishment. Her campaign pledges might have been notably more suspicious of Wall Street than were Bill Clinton’s, whose administration had deregulated the banking sector and appointed cabinet secretaries from merchant banks, but she clearly shares with her husband a commitment to an open, laissez-faire economy and the free movement of capital across borders. In this respect, the emails revealing her speeches to Wall Street banks weren’t even surprising. Whatever the policy particulars, any middle-class voter must have marvelled at the $225,000 speaker’s fee for her chat with Goldman Sachs.

Clinton’s establishment politics played out in more than one way. Perhaps the most dangerous aspect of her long immersion at the top of US policy-making was her tendency to speak in technocratic language. Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibbi (who has spent much of his career reporting on Vladimir Putin) writes that Trump voters told journalists that they simply couldn’t understand what Clinton was saying. Her complex, modulated and often highly technical language sounded great to coastal progressives, but flew right over the head of less educated voters.

Many reporters, myself included … heard voters saying they were literally incapable of understanding the words coming out of Hillary Clinton’s mouth.

‘When [Trump] talks, I actually understand what he’s saying,’ a young Pennsylvanian named Trent Gower told me at a Trump event a month ago. ‘But, like, when fricking Hillary Clinton talks, it just sounds like a bunch of bullshit.’

A disconnect of this size is about more than just fake news shared on Facebook. It speaks to a very real blind spot shared by many members of the liberal knowledge classes who voted for Clinton.

You know this demographic well, of course: if you’re reading this on New Matilda, you’re probably a member of it.

Highly-educated (often to postgraduate level), workers in the knowledge-cultural class are generally socially liberal, cosmopolitan, and outward-looking. They might sometimes have low incomes, but many are earning above-median wages. They are often rich in cultural capital and more likely to live in urban centres. They share values of tolerance and social liberalism, and are strong supporters of racial and gender equality, same-sex marriage and legal abortion. It’s easy to stereotype, but they tend to live in the sort of places where you can buy nice espresso coffee, and where the local drinking establishment is a funky small bar.

Many conservative voters do not live in this world. Indeed, they have begun to dislike this vision of the world. They harbour strong cultural antagonisms to the social position of typical members of the progressive classes, like Hollywood film stars, tech billionaires, university professors and mainstream news journalists.

The contrast between the gleaming campuses of the knowledge disrupters and the industrial decay of the rust belt is not just economic, but social and cultural. The relative prosperity of these sections of the economy, and their geographical concentration in certain cities and regions, further exacerbates this tendency.

LIBERALISM’S most damaging social construct is the one it finds hardest to acknowledge any problems with: the meritocracy. This is a project that claims to give the best jobs and the brightest prospects to the smartest and best-educated. Barack Obama is of course the shining example: a man who grew up at the margins of American society, but who took advantage of the opportunities of education to become a professor of constitutional law, and ultimately president. Hillary Clinton, too, was held up as a highly-accomplished and qualified candidate.

But is success in a meritocracy really about merit? In reality, as many working class voters suspect, the meritocracy is increasingly a sham. Social mobility in most advanced economies is declining, not increasing. In a privatised education system like the US, the spoils of the job market are reserved for those wealthy enough to purchase a qualification in a top university. Social connections and family ties still matter; indeed, the evidence suggests they matter more than ever. In the year 2016, US elites do not contain many Barack Obamas. They contain plenty of Mark Zuckerbergs: individuals who are certainly very talented, but who also happened to grow up in wealthy enclaves and enjoy top-quality private educations. The meritocracy is mostly made up of the children of rich parents, locking out talented outsiders unlucky enough to be born into poverty.

It’s no coincidence many voters on both the left and the right are increasingly hostile to experts. Hostility to experts is also a trope of illiberalism. The very basis of our liberal system depends on reason and expertise in the rule of law, the assertion of equality, the gaining of higher degrees, and the structure of an increasingly unequal meritocracy.

The growing sense that the experts at the top of the meritocracy are corrupt is fuelling the current climate of anti-rationalism. The left has become mistrustful of neoliberal think-tankers and economists, the right of humanities academics and climate scientists. Everyone hates journalists and politicians. Politicians at least get that they are unpopular. Journalists, with typical narcissism, have found the hostility difficult to comprehend.

If you oppose the current system, it’s not surprising you would also oppose the experts who champion it, and who seem to gain most from it. In the figure of the management consultant, the venture capitalist or the computer programmer, the expert is now someone who disrupts industries, shutters factories, and outsources jobs.

And, in truth, do the experts really deserve to be venerated? The quants and hedge fund traders in the merchant banks like Lehman Brothers and Goldman Sachs were meant to be experts: the best and the brightest. Look how their risk models turned out. As British philosopher John Gray wrote before the election, “when rattled liberals talk of the triumph of emotion over reason, what they mean is that voters are ignoring the intellectual detritus that has guided their leaders and are responding instead to facts and their own experiences.”

Trump offered voters the opposite of the liberal agenda of free markets and open borders. Instead of Clinton’s free trade, free advice and free love, he pushed social illiberalism, with overt displays of racism and xenophobia. But he combined that with promises of economic illiberalism, in the form of sanctions against offshoring, higher tariffs and Keynseian infrastructure and defence spending.

As the Brexit prototype suggested it would be, this combination of racial nativism and big government mercantilism proved wildly attractive with a certain segment of the electorate.

The flashpoint of the new populism is immigration. It was Trump’s anti-immigration and closed border policies that catapulted him rapidly into contention. The nativism and xenophobia struck an immediate chord with many American voters.

Voters oppose immigration for many reasons. It’s not just that they see immigrants as likely competitors for scarce jobs. It’s also that rapid immigration is destabilising. For those who grew up in relatively homogenous and monoglot communities, rapid demographic change is unsettling. This is one explanation for the superficial mystery of why white rural communities, which get the least immigration, are often the most hostile to it. Racist, anti-immigrant xenophobia is the core of the far-right in Europe, and the alt-right online.

But the social incomprehension cuts both ways. Liberal enclaves often look down upon their redneck cousins, with ill-disguised prejudice and disdain. As Jonathan Haidt wrote in July, progressives (who he calls ‘globalists’):

… often support high levels of immigration and reductions in national sovereignty; they tend to see transnational entities such as the European Union as being morally superior to nation-states; and they vilify the nationalists and their patriotism as ‘racism pure and simple.’

The smug cultural arrogance of progressivism has done no end of damage. If you’re worried about immigration, if you feel economically insecure, and if you’re sick of being told by jumped-up elites that believing that makes you stupid and a racist, the rhetoric of a Le Pen, a Hanson or a Trump can prove deeply attractive.

HISTORICAL epochs are often visible only after they’ve begun to fade into the past. We may be living at the juncture between two different social and economic systems.

The appeal of authoritarianism to a swathe of diverse electorates across the western world should alert us to the fact that something very big is happening in our body politics. The end of the post-war liberal consensus may be approaching.

It should be clear that the liberal project in Western democracies has now run into serious trouble. To pretend otherwise, as many are in the Democratic National Committee, is folly.

In the rear-view mirror, we can already see the neoliberal moment of globalisation and free trade receding. That moment gave us the “end of history” and the spread of a wide-ranging cosmopolitanism, symbolised perhaps most acutely by the global epidemic of urban hipsters. It also gave us radically transformed economies, with widespread de-industrialisation and anomie.

We are still making out the contours of the new landscape that is emerging. It is already frighteningly violent, intolerant and authoritarian.

What’s certain is that as we approach the end of 2016, something is changing quickly in western democracies. It’s something that Paul Ryan, the conservative Speaker of the House of Representatives from Wisconsin, seems to have recognised.

Even more than Trump, Ryan is the real winner from last week’s election. As Speaker, he will be the titular head of the House Republicans, at a time where they will control all three branches of the US government. Ryan will be the one to husband through the repeal of Obamacare, and multi-trillion dollar tax cuts for the 1 per cent. Long after Trump stumbles into history, Ryan may be seen as the real inheritor of the Republican ascendency.

“I want to congratulate Donald Trump on his incredible victory,” Ryan said straight after the election. “It marks a repudiation of the status quo of failed liberal progressive policies.” He may well be right.

The liberal project of a rational system with which to frame and judge human behaviour has been a tremendously attractive vision. It has spurred scientific knowledge and human flourishing, and emancipated women and slaves. But it is buckling under the strain of its own contradictions.

John Gray has been perhaps the most prescient predictor of the end of liberalism. He wrote in early November that “most liberals nowadays are secular in outlook, yet they continue to believe that their values are humanly universal.”

But, Gray observed, “it has never been clear why this should be so.” Progress is not inevitable. Reason does not always triumph. That has been shown many times throughout history. It may well be true in our own time.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.