Australia is entering a new era of political instability, and it has a lot to do with a feeling among many of being ‘left behind’ in the race for prosperity. Ian McAuley explains.

An opinion poll published last week reveals a political division cutting across traditional party loyalties and pointing to a possible populist rejection of economic openness.

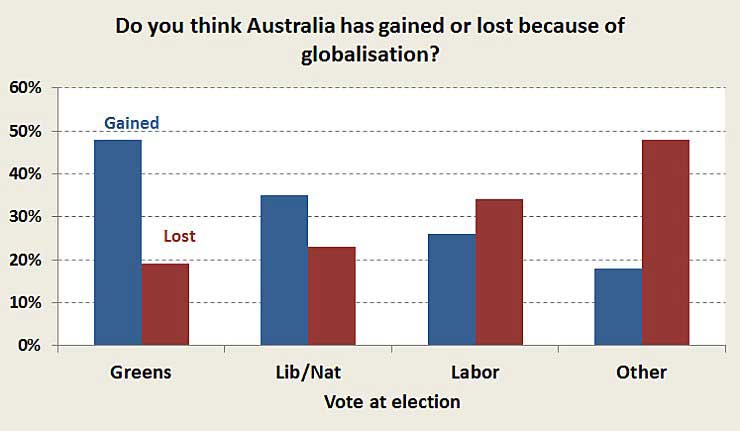

Essential media asked whether Australians had gained or lost because of globalisation – which they describe as “the increase of trade, communication, travel and other things among countries around the world”. The results are shown in the chart below.

Three points stand out.

One is a polar difference between Green and “other” voters. Those 23 per cent who voted other than Labor or Coalition are far from a homogeneous movement. That has clear implications for the government’s dealings with the Senate, where there will be no united bloc of ‘crossbenchers’.

Another is that the notion of a ‘left-right’ spectrum, in which the Greens and Labor are close to each other, does not hold. Green and Labor supporters are a long way apart on this important issue.

And the third, perhaps the most obvious, is that those who voted “other” are most likely to reject globalisation. This group includes everyone from Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party through to Nick Xenophon’s Team, and although they vary tremendously on issues of tolerance, social liberalism and understanding of science, they are generally protectionist in outlook.

Unsurprisingly the poll found that younger people and those with a higher education were more supportive of globalisation than older and less educated people. That explains some of the Greens’ response.

Another Essential poll on the benefits (or otherwise) of trade with other countries revealed similar results. A majority of “other” voters believed trade caused a loss of jobs, while Green and Coalition voters were more likely to believe trade helps create jobs.

There is no single ‘correct’ answer to these questions. In general, countries that are open to the rest of the world through trade and immigration are more prosperous than those that are comparatively closed. But only in certain conditions does economic openness result in the benefits of openness being shared. To understand the relationship it’s useful to look at the economic history of the last 72 years.

The post-1945 economic order – from openness to crony capitalism

It’s easy to assume the post-1945 economic system, which saw full employment, rapidly-rising living standards and a convergence of incomes, to have been a fortuitous outcome, but in reality it was the result of deliberate planning.

In 1944, delegates from the soon-to-be-victorious Allied nations came together in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to hammer out a postwar international economic order. Their objective was to avoid a re-emergence of the economic isolationism that had contributed to the 1930s Depression, the rise of Fascism and Nazism and the 1937-1945 Asian and European wars.

On the domestic front governments were concerned that with millions of demobilised soldiers entering the workforce there may be a repeat of the post-1918 political unrest, and even a slide back into depression.

Governments were mindful that in such conditions, communism posed a very attractive alternative – communism by its very presence as an alternative to keep capitalism on its best behaviour.

It was fortuitous that in the postwar period, the USA and Britain had Democratic and Labour Governments, committed to Keynesian economics. Similarly in Australia the Chifley Labor Government laid out a platform of shared prosperity in the White Paper on Full Employment.

The prevailing philosophy of the time was that economic openness was a means to an end. Australia, while being slow to remove tariff protection, benefited from the multilateral trade and investment institutions that emerged from the Bretton Woods settlement – the IMF and the GATT (the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, later to become the WTO).

Although sustaining full employment was to become an elusive goal, the philosophy of economic openness as a means to shared prosperity was a guiding principle as the Hawke Government removed tariff protection, opened up sectors of the economy to competition, and reduced regulation of financial and labour markets. Almost all Australians benefited from these reforms.

But from around the mid-1980s (about the same time as those who remembered the dismal history of the 1914-1945 period were passing from public life, and as Soviet-style communism was clearly exposed as a failed system) economic liberalism started to take on a life of its own, and expanded to include the package we now recognise as “neoliberalism”.

The new expanded package included policies of privatisation of government enterprises, even if those enterprises were operating efficiently; deregulation, regardless of endemic distortions in unregulated markets; ‘small government’, in disregard for the need for public goods; weakening of labour unions; and a scaling back of safety and environmental protection.

HELP SUPPORT NEW MATILDA’S WRITERS. FUND OUR LATEST POZIBLE CAMPAIGN HERE.

Economic growth, particularly in the private sector, became the overriding objective. Any resulting rise in unemployment and inequality was seen as merely a transitory problem. In any event, inequality wasn’t seen to matter much, because “a rising tide would lift all boats”.

In recent times, even neoliberalism has tended to give way to a system best described as creeping cronyism, manifest in the power of special interest groups such as mining firms, banks and health insurers to secure economic privilege.

As corporate executives appropriate eight-digit salaries for themselves, as the wealthy come to consider paying taxes a mug’s game, and as rent-seekers and real-estate speculators prosper, inequality grows and any notion that there is some connection between contribution and reward is lost, to be replaced by cynicism and deep mistrust of “policy elites” – politicians in the established parties and public servants in Canberra’s corridors of power.

The backlash – from openness to defensive populism

Britain’s Brexit took many by surprise, but there were plenty of warning signs. Even the IMF (a Bretton Woods Institution) was warning about the political and economic consequences of inequality, and of public perceptions that economic systems were unfair.

Globalisation and economic openness, although of benefit to all in their postwar manifestation, now suffer the curse of guilt by association – association with the destructive forces of neoliberalism and crony capitalism.

The association is unfair, but it’s strong, having been claimed so often by the “right” in justifying the unjustifiable – claiming for example that the Trans-Pacific Partnership, with investor-state dispute settlement arrangements, carries the same benefits as were gained from participation in GATT and WTO trade liberalisation, or claiming that “there is no alternative” to selling public assets, as if there is some self-evident logical link between economic openness and privatisation.

The Essential poll reveals that many Australians hold the same beliefs that have led to Brexit in the UK, to the rise of Trump in the USA, and the rise of far-right parties in mainland European countries.

It is notable that in Queensland and Western Australia, the states most strongly affected by the end of the mining boom, One Nation has done well in the recent election.

In view of the evidence of growing discontent from those who feel left behind, it’s therefore puzzling that the Coalition’s main economic ministers, Scott Morrison and Mathias Cormann, remain dogmatically committed to “small government”, neoliberalism and accommodation of rent-seekers.

Turnbull and others, unless they are utterly politically inept, must be aware of the risk of backlash, but perhaps they are hoping to stave off the rise of far-right populism by having the Coalition occupy some of the same ground that One Nation claims.

It’s a strategy born of necessity or even desperation, but giving some say to the extremists in the Liberal and National Party may just hold the Coalition together until the next election.

Labor must be revelling in seeing the Coalition so divided and pursuing such a high-risk strategy, but it has its own tensions. Labor’s economic spokespeople such as Chris Bowen and Andrew Leigh may be committed to economic openness, but as the Essential poll reveals its supporters don’t seem to be so enthusiastic.

Labor therefore has the hard job of restoring the community’s faith in globalisation and economic openness, and disassociating the best parts of globalisation from neoliberalism and crony capitalism. It has to reach beyond “progressives”, who need no convincing, to gain and hold the trust of those who feel left behind, and who may be tempted to follow false economic prophets offering isolationism, protectionism and racial and ethnic exclusion as a path to economic security.

As John Menadue puts it, “those at the centre of public life have a responsibility to ensure that the benefits of globalisation are shared and that the vulnerable are protected”.

Otherwise, our future will follow the path of those South American countries that flourished when times were easy, and in taking the tempting path of populism have found themselves in an economic stagnation of entrenched poverty and entrenched privilege.

HELP SUPPORT NEW MATILDA’S WRITERS. FUND OUR LATEST POZIBLE CAMPAIGN HERE.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.