The popular poster campaign has started a useful conversation, but one that needs a little more context, writes Zushan Hashmi.

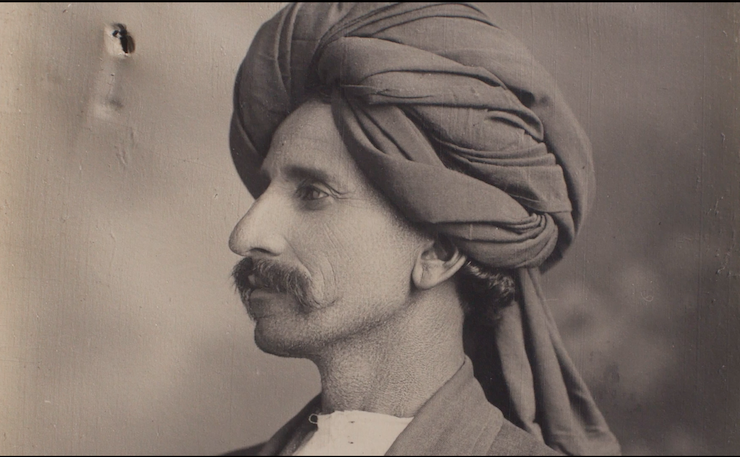

Earlier this year, numerous posters with photos of immigrants and the word ‘AUSSIE’ began appearing on walls around Australia’s towns and cities. In particular, the picture of a man wearing a turban and sporting a type of moustache frequently seen across South Asia, garnered a lot of media attention.

It turned out that Peter Drew, famous for his ‘Real Australians say Welcome’ posters, was behind the campaign, which aimed to “embrace our neglected histories and expand Australia’s identity”. However, the man seen in the most popular of these posters, Monga Khan, brings an important question to light – who exactly were the ‘Afghan’ Cameleers?

Unfortunately, Peter Drew himself, along with others who have blogged and written on the topic, seems to have only further distorted the answer to this question. Most of these writers and bloggers referred to Monga Khan as an Afghan, with some even calling him an “Afghani”, which happens to be the currency of Afghanistan, and is not the appropriate word to be used when referring to a person from Afghanistan.

Moreover, initial news reports regarding the posters called him a cameleer. However, as Drew has noted on his website, according to letters dating back to 1916 held by the National Archives of Australia, Monga Khan was in fact an Indian man, from the village of Batrohan, located in the state of modern-day Haryana. Additionally, he was a “licensed hawker”, and according to different reports he sold Indian goods such as spices.

Yet I do not believe that Peter Drew or any other bloggers or writers should be criticised for this misinformation, or rather, for presenting Monga Khan inaccurately. The issue behind this distortion of Monga as a cameleer and an Afghan is very much rooted in our broader understanding of the history of the cameleers.

As mentioned, the word Afghan is used in a contemporary sense to refer to someone from Afghanistan. However, this has not always been the case.

For hundreds of years, Afghan as a term was primarily used by Persian speakers to describe another ethnic community, known as the Pashtuns (also called the Pakhtuns and Pathans). In the twenty-first century, the Pashtuns made up the largest ethnic group in Afghanistan, yet more Pashtuns live in Pakistan, particularly in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, the North Western province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Karachi.

The reason I provide this background is because the Pashtuns along with the Baloch (another ethnic group found in South Asia and Iran), probably played the most significant role in non-Aboriginal explorations of the Australian outback in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as cameleers. For example, the most famous cameleer, Bejah Dervish, was a Baloch.

To further understand why the Afghan cameleers came to be known as Afghan in the first place, some additional digging into South Asia’s geopolitical landscape between the 1860s and the early 1900s is required.

At the time of the cameleers, the British Raj was in control of India, which encompassed modern-day Pakistan and Bangladesh, as a single colony. It was not until 1893 that the formal border that we have today dividing Afghanistan and Pakistan, known as the Durand Line (it is still largely unrecognised in Afghanistan), was established, hence separating the regions of FATA and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (as named today) from Afghanistan, and also further dividing Balochistan between Afghanistan, and pre-partitioned India. Forwarding 54 years to 1947, the partition of India took place, and Pakistan was formed, with the areas south of the Durand Line becoming a part of Pakistan.

Interestingly enough, a large number of cameleers came from the southern regions of the Pashtun lands (often referred to as Pashtunistan), Balochistan, Punjab, and Sindh, which are all territories of Pakistan today, according to the book Australia’s Muslim Cameleers: Pioneers of the Inland, 1860s-1930s by Philip Jones and Anna Kenny. The book also notes that some of the earliest cameleers were in fact Pashtuns from south of the Durand Line, while furthering the view that the ‘cameleers’ became an umbrella term to describe most people who travelled to Australia from the South Asian region at the time, even if they were, much like Monga Khan, hawkers, merchants, or traders.

Unfortunately, another misconception that exists is that the cameleers were solely from areas in modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan. Several cameleers happened to come from Turkey, parts of Northern India, including Rajasthan, Gujarat, Punjab, and even Egypt, which the British had occupied in 1882. Moreover, just as the majority of cameleers came from areas that make up modern-day Pakistan and India, they were also mostly Muslims, however, contrary to popular belief, a sizeable number of cameleers also followed different faiths, such as Hinduism and Sikhism.

There are a couple of reasons why this topic needs to be studied and discussed by Australians.

Firstly, a lot of the cameleers did return to their homelands, and may very well have passed on stories to their children and friends, and possibly even written books about the years they spent here in their local languages, which have not been looked into extensively. These stories and accounts could provide us with some fascinating insights into the people who helped build the foundations of contemporary Australia.

Secondly, without undermining the important role of the cameleers from Kandahar and Kabul, it should be remembered that the ‘cameleers’ were not just Afghan, or simply cameleers, but rather a very diverse set of people themselves, who came from different cultures, held different beliefs, carried out different tasks and jobs, and even spoke different languages.

It may well be that the more we study and try to understand this, the better we can appreciate the great diversity of Australia’s population today, which Peter Drew has worked hard to promote and make available through his poster campaigns.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.