EXCLUSIVE: A top Australian University is feeling the heat after it apparently ignored a report urging it to prove the merits of its ethical investment policy. Climate activists in particular have seized on the review. Thom Mitchell reports.

The University of New South Wales has failed to articulate a strategy to implement, monitor, and report on its ‘responsible investment’ policy, a leaked internal document reveals.

In an ‘Ethical Investment Review’ conducted by consulting group Mercer, the University is given a rating of just 4 out of 50 for responsible investment.

Delivered to UNSW in May last year, the report praises the University for making a responsible investment statement, but urges the institution to take “a more strategic approach”, indicating the policy it puts forward to the public has not been underpinned by a meaningful process.

The University’s ethical investment policy states it “will not knowingly and directly invest in an organisation that operates at the expense of the environment”. Yet in its report, Mercer noted UNSW “does not articulate a strategy for implementing, monitoring and reporting on the policy statement to its stakeholders”.

“In our opinion,” the consultants write, “this leaves [UNSW] exposed to significant reputational risk”.

Despite pressure mounting on the University of New South Wales to come clean on investments in polluting industries, and a number of recent climate protests, the advice in the document appears to have been ignored.

Former Liberal Party Leader Dr John Hewson told New Matilda it wasn’t good enough for the university not to clearly articulate its implementation of the policy.

“Just saying ‘we have this policy, and don’t you worry about that, just trust me, we’ll do it – I think people want to see evidence that it’s actually being adhered to,” he said.

Dr Hewson now chairs the Asset Owners Disclosure Project, which profiles the exposure of large funds to fossil fuel companies. The former opposition leader said he was “very concerned that the financial community as a whole is running a very significant risk of a climate induced financial crisis”.

Two weeks after students staged a sit-in at the Vice-Chancellor’s building – the sort of escalation Mercer warned was likely to occur if UNSW didn’t act – Dr Hewson said the University’s continued refusal to be transparent and disclose its exposure to fossil fuels represents an “attempt to defend the indefensible”.

“You would only resist that if you had something to hide – if you didn’t think that you were meeting sensible environmental and social governance criteria, for example, or that you were living up to your declared investment objectives,” he said.

“If you are doing it, you’d be proud of that fact. You’d be keen to tell people, rather than ducking it. If you duck it – if you don’t want to disclose, if you don’t want to be transparent – it suggests you’ve got something to hide.”

New Matilda is an independent Australian media outlet which depends on subscriptions for its survival. You can support our work here – subs start from just $6 per month.

Trevor Thomas, the Managing Director of EthInvest, which specialises in developing socially and environmentally responsible portfolios, said that after 12 months you would expect there to be some evidence that the University has begun to implement the report’s recommendations.

“I think that as the consultant proposed a way forward for the University to start thinking about these issues, and to move towards implementing policies that made it clear that their lofty statements of principle were actually carried through into action and made accountable,” he said.

“The report itself argues persuasively that the University should move on this issue, that it risks its reputation, that it risks being tarnished if it doesn’t do anything, and that at the moment it’s inherently compromised because it’s got lofty ideals and very little evidence that suggests that the University’s living up to those ideals.”

Mercer canvassed a range of options on how to develop a more structured approach, and recommended UNSW begin a process to establish what its position on responsible investment issues is, and how that will actually be borne out. A spokesperson for the University would not comment on the detail of the report or what, if anything, is being done to respond to it.

Instead, a general assertion that “the University regularly reviews its investments to ensure that they align with our objectives and strategy” was offered.

“All of UNSW’s share investments are handled through managed funds, in which professional fund managers make investment decisions on behalf of large groups of investors,” the spokesperson said.

“All of UNSW’s investment managers, except one, are signatories to the UN Principles of Responsible Investment; the one exception is controlled by a company that is a signatory.

“In accordance with our Investment Policy, UNSW ‘will not knowingly and directly invest in an organisation that operates at the expense of the environment, human rights, the public safety, the communities in which the organisation conducts its operations or the dignity of its employees’. This policy has been adhered to.”

But that policy statement is nothing more than a fig-leaf, according to Breana Macpherson-Rice, a student spokesperson for Fossil Free UNSW. Macpherson-Rice said the statement was “defunct” as it only promised to not invest directly in ways that harm the environment, which is meaningless when you consider all of the University’s investments are effectively indirect.

Documents from a 2014 freedom of information request reveal that, at that time, the University had a $50 million exposure to fossil fuel equities. The managed funds UNSW was invested in at May last year list companies like Exxon Mobil, Woodside Petroleum, BHP and Rio Tinto among their top stocks.

The University did not respond to questions around whether its money was being indirectly invested in those firms. Macpherson-Rice said stakeholders are sick of being left guessing.

She said a survey carried out last year found that 78 per cent of students support divestment, and pointed to an open letter co-signed by more than 150 prominent academics and alumni calling for divestment.

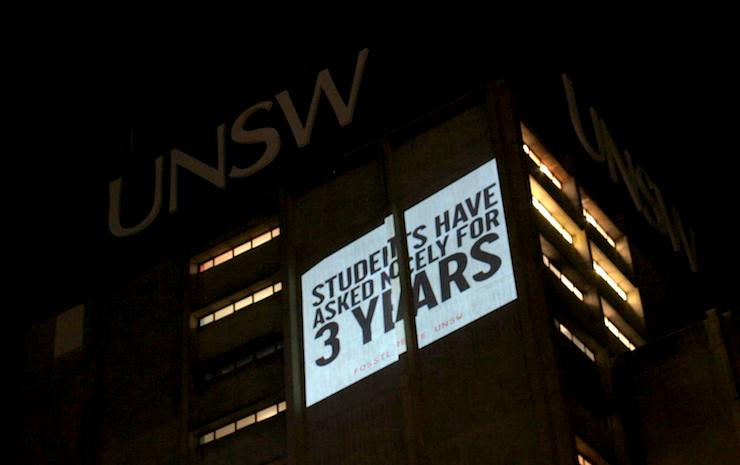

“Students and staff began asking for divestment from fossil fuels in 2013, but we have not yet had so much as a meeting to present our case,” Macpherson-Rice said. “We have been incredibly frustrated with the lack of any engagement or transparency on our University’s fossil fuel investments”.

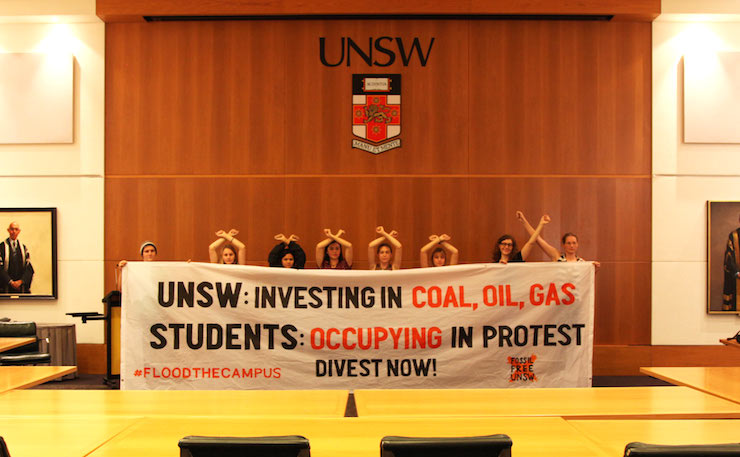

Earlier this month she participated in an occupation of the Vice-Chancellor’s building, which lasted 36 hours but failed to shift VC Ian Jacob’s position on the issue. The escalation in campaigning came as part of a national wave of actions staged across seven Australian Universities.

It forms part of the global divestment movement, which has seen funds representing more than $3.4 trillion in assets pull their money from coal, oil or gas. Over the past two weeks, students in the United States have been ramping up their own campaigns, in an escalation which has led to at least 62 arrests.

62 students across the U.S. arrested in the past 2 weeks, taking bold action for divestment. Photo @azds #leadwithus pic.twitter.com/Nqvrbes7Uo

— 350 dot org (@350) April 30, 2016

From Dr Hewson’s perspective, the moral pressure being applied by divestment activists may end up being a financial boon. “You don’t have to be too smart to get out of coal shares, and maybe even oil and gas shares, given their performance over the last couple of years compared to a whole host of other low-carbon alternatives,” he said.

While not specific to fossil fuels, the report from Mercer finds that “over the near to medium term Responsible Investment strategies have performed as well as the University’s current strategies”. Over the long term, ethical options have performed slightly less well, but the report notes that as the responsible investment field develops that’s likely to change.

Trevor Thomas said that Universities, “as centres of learning and science-based, forward-thinking institutions”, should be actively managing the ethical impacts of their investments.

“I absolutely think that it’s the right of staff and students to demand that the University have clear policies around investment and is held accountable is reporting against that policy,” he said.

Given Universities are funded by government and, in the case of UNSW a number of partnerships with fossil fuel companies, “one has to ask the question about whether those relationships come to the front of mind when these conversations about divestment or ethical investment strategies come up”.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.