Some the world’s most powerful and wealthiest corporations have their backs to the wall right now, and Australian corporations are no exception. The volatility of commodity prices and the contraction of the Chinese economy (and the global economy generally) has left many corporations in states of acute uncertainty.

But there are other equally pressing concerns that expose the inner workings of some of Australia’s leading companies:

- 7-Eleven having to fork out up to $100m for underpaying its already low paid workers

- the Australian Securities and Investments Commission prosecuting Westpac over interbank lending rate manipulation

- banks facing the prospect of a Royal Commission because of a variety of misdemeanours

- Unaoil caught out making corrupt contract payments to secure contracts for their clients

- twenty-seven of the top 100 ASX companies caught paying “facilitation payments” to foreign public officials in order to facilitate business deals

- BHP forced to cough up millions for an environmental disaster in Brazil

- revelations of massive tax avoidance in the Panama papers

The latter is nothing new: corporations have long been siphoning trillions of dollars into offshore “shell” companies, effectively sucking money out of public accounts, and by extension, schools, hospitals, welfare and infrastructure. (Thomas Piketty estimates that unregistered financial assets held in tax havens is around approximately $6.4 trillion, eight per cent of the annual global GDP).

Despite the occasional sabre rattling, most liberal democratic governments have either turned a blind eye to dodgy offshore investments or simply gone the other way by granting further corporate subsidies and tax cuts. Interestingly, such generosity has not extended to the nation’s less well off. The former Abbott and now Turnbull Coalition governments have sought to address the so-called “debt and deficit disaster” not by taxing cashed-up corporations and private individuals, but rather by making significant cuts to health, education and welfare, impacting most directly on some of the nation’s most disadvantaged communities.

Again, we shouldn’t be too surprised by this, since it’s what successive governments have done in order to shore up the interests of the rich and powerful. Lobbyists, conservative think-tanks and media apologists have aided and abetted this situation, thereby ensuring that it’s business as usual. But is it?

Corporations are of course part of the great mosaic of global inequality. Despite the endless stream of books and articles chronicling the harmful effects of socio-economic inequality, wealth and income disparities have deepened over recent decades. Economists Thomas Piketty, Robert Reiner, Joseph Stiglitz, Paul Krugman, Andrew Leigh, John Quiggin and many others have alluded to this very fact, pointing out that if political leaders were serious about seeking to increase the circulation of money in the capitalist economy they would hand it to the poor rather than the rich. Put simply, those in the lower rungs are far more likely to spend their income rather squirrel it away in savings – they have little choice.

Corporations are of course part of the great mosaic of global inequality. Despite the endless stream of books and articles chronicling the harmful effects of socio-economic inequality, wealth and income disparities have deepened over recent decades. Economists Thomas Piketty, Robert Reiner, Joseph Stiglitz, Paul Krugman, Andrew Leigh, John Quiggin and many others have alluded to this very fact, pointing out that if political leaders were serious about seeking to increase the circulation of money in the capitalist economy they would hand it to the poor rather than the rich. Put simply, those in the lower rungs are far more likely to spend their income rather squirrel it away in savings – they have little choice.

Some of the world’s richest people like George Soros have come to the same realisation – namely, that giving money to the already wealthy is foolhardy and counter-productive when it comes to achieving the dubious aspiration of economic growth. Such simple logic, however, has seemingly failed to persuade many of Australia’s political and business leaders about the merits of wealth and income equality, insisting instead on advantaging the rich over the less well off.

Thomas Piketty shocked many observers when he noted in the bestselling Capital in the 21st century that most western nations are as economically divided as they were 100 years ago and that levels of wealth concentration (in the form of “patrimonial capitalism”) are now even more pronounced. While the rich enjoy the benefits of increased wealth, most workers in capitalist economies have over the past 40 years experienced sustained wage stagnation and a decline in real incomes. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis exacerbated this trend, with up to 50 million people around the world losing their jobs, and wage rises further stalled. This occurred at the same time as many leading banks – some of the very institutions responsible for the financial crisis – were being bailed out by governments while hundreds of thousands of people lost their incomes and homes. Many cities in the US were laid to waste by the ravages of the GFC, a situation that endures to this day.

Despite public outrage over the reckless risk-taking of leading financial institutions and the excessively generous salaries granted to CEOs, little has been done since 2008 to stem the huge payouts awarded to these already wealthy individuals.

On the other side of the ledger, we’ve witnessed a steady decline in the power of organised labour, with only 10 per cent or so of the OECD workforce paid-up union members, and around 15 per cent in Australia. This seems counter-intuitive at a time of such huge wealth and income differentials, but the spectre of casualisation, lack of employment opportunities, and low waged and de-unionised workforces in other countries have increased the power of employers and instilled fear and trepidation among workers. Add to this myriad free trade agreements (placing further downward pressure on wages), the increased power of corporations over governments thanks to the Trans-Pacific Partnership, along with political and legislative attacks on the union movement – as in the case of the Abbott government’s creation of the Royal Commission into Trade Union Governance and Corruption – and we have all the ingredients for diminished union power. The result is a circular process: the weaker the labour movement the more likely that wealth and income differentials will deepen.

The consequence of all this is a fragmented picture of global and regional inequality. Although the overall total of global wealth has increased over recent years, the data indicates clearly that wealth and income divides within nation states remain deeply entrenched. This enduring culture of structural inequality around the world is glaringly evident.

The Washington-based multi issue Institute for Policy Studies in 2015 has distilled enormous amounts of information on wealth inequality, drawing from various credible sources around the world (including from some of the leading financial corporations). Despite the growth in the quantum of global wealth, and some signs of diminished levels of overall inequality (mainly because of the rise of a middle class in China and India), the gulf between the global rich and poor remains acute, as it does within nation states.

Among other things, the IPS data shows that “nearly three-quarters of the world’s adults own under $10,000 in wealth. This 71 per cent of the world holds only 3 per cent of global wealth”. Equally striking, the world’s richest people with over $100,000 in assets, make up less than 10 per cent of the world’s population but account for nearly 85 per cent of global wealth. The greatest concentrations of individual wealth (including three quarters of the world’s millionaires) are found in Western and European countries. “Ultra-high net worth individuals’ — those earning in excess of $30 million, “own 12.8 per cent of total global wealth, yet represent only a tiny fraction of the world population”. The very rich – 10 of the world’s leading billionaires – “own $505 billion in combined wealth, a sum greater than the total goods and services most nations produce on an annual basis”. The report further notes that in March 2016 there were, worldwide, 1,810 billionaires, nearly double the number in 2009. “These 1,810 billionaires together hold $6.5 trillion in wealth”, says the Institute.

On the other hand, 3.4 billion of the world’s adults with accumulated wealth of less than $10,000 possessed $7.4 trillion in net worth. The richest one per cent, those with wealth over half a million dollars, “owned 39.9 per cent of the world’s household wealth, a total greater than the wealth of the world’s poorest 95 per cent, those adults worth under $150,145”.

According to Thomas Piketty, the biggest concentrations of income have occurred in the Anglosphere countries, with the one percenters in the US, Canada, the UK, and Canada and Australia increasing their share of income by between 10 and 18 per cent. A similar pattern obtains with the top 10 per cent in these countries, a phenomenon that Piketty describes as “the rise of the super manager: an Anglo-Saxon phenomenon”.

Despite all the talk of a “fair go” and the “lucky country”, wealth and income inequality is rife in Australia. According to an Australian Council of Social Services report, Inequality in Australia: A Nation Divided, Australian income inequality is higher than the OECD average, with top earners accruing five times more than the lowest paid workers. While overall wages have risen, the picture is patchy, with unequal wage increases serving to increase income inequity. Those atop the income ladder have experienced a much faster rate of income growth than the bottom 20 per cent (a group made up largely of sole parents, people over 65 years of age, and those reliant on welfare and/or from non-English speaking backgrounds and regional areas). Additionally, top earners have benefited from the doubling of investment income between 2004 and 2010, the key driver of income inequity.

When it comes to wealth distribution, the divisions are more acute: “A person in the top 20 per cent has around 70 times more wealth than a person in the bottom 20 per cent”, says ACOSS, adding that the top 10 per cent of households own a little under half of all wealth (derived mainly from property investments, shares and superannuation), while the bottom 40 per cent of households own less than 5 per cent. Importantly: “the average wealth of a person in the top 20 per cent increased by 28 percent over the past eight years, while for the bottom 2o per cent it increased by only three per cent”.

These figures demonstrate the enduring nature of socio-economic inequality. More importantly, they reflect the consequences of an ideology that privileges market forces above all else and which views the concentration of private and corporate wealth as the natural order of things. They also reflect the ability of the wealthy in the current era to profit personally at the expense of the poor and marginalised and the greater social good. The vacuity of the ‘trickle down’ effect means that the sum of nation’s material wealth remains disproportionately in the hands of a few and thereby, in effect, often denying others access to some of life’s most basic necessities. It’s been estimated that money secreted away in private accounts of individuals is in the order of $35 trillion, the tax revenue from which is certainly enough to make a significant dent in global poverty. It could also prevent what Professor Gideon Polya refers to as “global avoidable mortality” which results largely from deprivation and deprivation-exacerbated diseases in the developing world (minus China) – currently stands at 17 million deaths per year. Wealth redistribution could further improve education, welfare, housing and a variety of other unmet needs of some of the most deprived populations around the world.

But rather addressing such inequities, corporate self-interest has over recent years reached new, extraordinary heights. The most brazen and life threatening development of all has been linked to the ambitions of the world’s leading mining companies who, in spite of all the available evidence, continue to emit record levels of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere which already exceeds 400 parts per million. Governments around the world, partly because of pressure from corporate lobbyists, continue to grant mining leases even in the face of the most alarming climate science.

Take the granting of a mining lease to the Indian company, Adani Mining Australia, by the Queensland state government. It’s anticipated that over the course of its existence the $21 billion Carmichael mine in Queensland’s Galilee Basin is likely to spew over four billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere – in addition to wrecking the local environment. We’re told by leading Coalition politicians that the exporting of coal to India is an act of kindness, ensuring that millions of poor Indian people are no longer reliant on dung fuel.

Former Prime minister Tony Abbott and current Minister for Resources, Energy and Northern Australia, Josh Frydenberg, have suggested, respectively, that this coal is “good for humanity” and is based on a “good moral case”. Both seem oblivious to the blindingly obvious irony: namely, that the burning of coal on such a scale will contribute to the deaths of millions of people around the globe and populations movements on a scale as yet unseen. (Interestingly, the World Health Organisation estimates that pollutants from burning carbon fuels kill seven million people each year. See here.)

Yet far from curtailing the powers of corporations, governments, in cahoots with other powerful interests, have granted greater impetus to these entities. How? First, through the provision of international trade agreements such as the TPP which, in effect, gives increased legal powers to corporations in their pursuit of profits, meaning they can prosecute sovereign governments if their actions impinge on commercial activity. As numerous commentators have pointed out, this is one of the greatest threats to democracy in recent times.

Second, governments across the globe have introduced legislation to protect the interests of corporations by preventing activists from protesting mining projects and reducing penalties for mining companies breaking environmental laws, as has recently occurred in New South Wales, Tasmania and Western Australia, with the result that protestors now face hefty fines and lengthy jail terms for challenging mining projects.

Third, governments have de-funded key environmental organisations, limited legal access of groups seeking to challenge mining operations, and limited funding to NGOs by cutting charitable funding status.

Fourth, governments in some nations, like Australia, have linked domestic policies ever closer to the requirements of business, with university research in Australian, for instance, tagged to “commercial outcomes”. The result is the commercialisation and privatisation of areas of knowledge previously in the public domain.

Fifth, corporations direct significant sums of money in the form of donations to conservative think tanks, universities and political parties to advance their commercial interests.

Sixth, through various technologies and data gathering operations, corporations are increasingly accessing information on various populations, again to promote business interests.

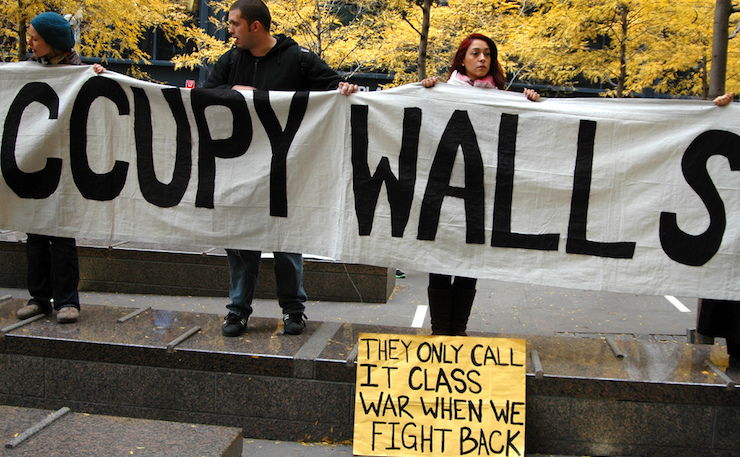

Many of the above are rear-guard actions by what in effect is a pro-fossil fuel alliance of governments and corporations hell-bent on ensuring business as usual. No one doubts the ability of this alliance to achieve its goals, at least in the short-term. That said, the forces ranged against neoliberal orthodoxy in the form of the global environmental justice movement, and anti-neoliberal movements like Occupy in the US, Indignados in Spain and more recently, Nuit Debout in France – not to mention the growing zeitgeist for systemic change – is likely to radically transform the current global system as we know it. Whether this can be achieved before the onset of runaway climate change, thanks in part to corporate greed, is another question.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.