ANALYSIS: In the wake of a visit by Iran’s Foreign Minister, relations between the nations are improving. In truth, the two countries have always been closer than they appeared, writes Michael Brull.

So, why have relations with Iran improved?

Foreign Minister Bishop noted a few areas she had discussed with Iran’s Foreign Minister

in their press conference during his visit.

She pointed to three key areas: “our enthusiasm for enhancing our trade and investment ties, as a result of the conclusion of the P5+1 Agreement…. the fight against terrorism that is occurring in Syria and Iraq, where we both have interests in defeating ISIL or Daesh, and we had a detailed discussion about that… defeating the people smuggling trade and issues of illegal immigration into our country.”

According to the ABC, Australia is hoping to send over 8000 asylum seekers back to Iran. It is no secret that Australia is determined to stop the flow of asylum seekers, so this is naturally a point of interest. Yet Australia is not interested enough in this area to negotiate with Daesh or Syria, so it is unlikely that this is a major factor in our improved relations with Iran.

Working with Iran to fight Daesh makes a lot more sense, given that we have gone to war with Daesh in Iraq and Syria. In Iraq, Shi’ite militias often depend heavily on Iranian support. In Syria, the Bashar al-Assad government is one of the leading forces fighting Daesh, along with Lebanese political party and militia Hezbollah. Both are supported by Iran. Given that Australia is a minor player in the war, it makes sense to work together with those fighting the same enemies. Given the political difficulties of the US coordinating its strategy with Iran, it is possible that Australia is acting as an intermediary for the US in some way.

Working with Iran to fight Daesh makes a lot more sense, given that we have gone to war with Daesh in Iraq and Syria. In Iraq, Shi’ite militias often depend heavily on Iranian support. In Syria, the Bashar al-Assad government is one of the leading forces fighting Daesh, along with Lebanese political party and militia Hezbollah. Both are supported by Iran. Given that Australia is a minor player in the war, it makes sense to work together with those fighting the same enemies. Given the political difficulties of the US coordinating its strategy with Iran, it is possible that Australia is acting as an intermediary for the US in some way.

For her part, Bishop has repeatedly indicated that she regards Iran as an important element of the fight against Daesh. For example, in April 2015, she said that she was keen to visit Teheran, as “Iran is deeply involved in building the capacity and defeating ISIL, so it’s an opportunity to discuss our collective interest in countering this form of particularly violent and brutal terrorism”. In a speech to the Sydney Institute later that month, she repeatedly identified the role of Iran in the fight against Daesh. For example, Bishop said:

- “I met with the leaders of Iran to discuss our common interest in building the capacity of the Iraqi Government to drive Da’esh from its lands and re-establish governance over its territory.”

- “As it was put to me last week, Da’esh is an equal opportunity murderer. Tehran warns that Da’esh must be prevented from capturing the cities of Damascus and Baghdad – for these were the capitals of the ancient caliphates of centuries ago.”

- “Over the past 18 months in my discussions with numerous senior leaders and officials in the Middle East and Europe, many have expressed the fear that we are facing a generational struggle against Da’esh and likeminded extremists and the ideology that drives them.

Iran’s President Rouhani described Da’esh as a cancer that could metastasise across northern and central Africa, Middle East, Afghanistan, Pakistan and into South East Asia.”

Trade with Iran is also an important issue, as we will see.

The US, Geopolitics, And Tanya Plibersek

Traditionally, politics and trade have been treated as separate issues in our relationship with Iran. I suspect the major impetus for improved political relations with Iran, and restraint in political rhetoric about Iran is the rise of Daesh. After joining the quagmires in Afghanistan and Iraq, Australia is not keen to get bogged down in another war in the Middle East, and neither is the US. If we are going to go to war in Syria and Iraq, coordinating the war effort with Iran, one of the major players in both conflicts, is somewhat sensible. This coordination indicates that our wars have limited aims. Rather than waging a war to overthrow Assad, our involvement is relatively narrowly conceived, and apparently targeted solely at Daesh.

Coming from the political right, Bishop’s pragmatic approach to Iran has shifted political discussion to the left, away from warmongers and confrontation with Iran. For example, conservative ALP apparatchik Tanya Plibersek, the shadow foreign affairs spokesperson, criticised Bishop in August last year for dealing with Iran. On ABC radio, Fran Kelly said to Plibersek “That’s smart, isn’t it, for Australia to be keeping Iran in on the loop on this given the support Iranian forces are giving to the Iraqi government, in terms of training and support for the Shiite militia and the fight against ISIS.” Plibersek replied: “Well, I think it’s for the Foreign Minister to explain why she’s singled out Iran for consultation. Iran is one of several countries in the region that are supporting different sides of this conflict. Iran obviously is the country that has backed Assad, the brutal dictator of Syria, and I think it’s really up to the Foreign Minister to explain why she’s singled out Iran for consultation.”

Now, the centre of political gravity has shifted. This week, Plibersek announced that “Labor has always said that we should engage with Iran… We’ve always said that Iran will have to be part of the solution in Syria… In fact, we’re not at war with Eurasia, we’ve never been at war with Eurasia, we’ve always been at war with Eastasia”. Okay, maybe she didn’t say that last sentence, but it’s still an accurate reflection of the traditional honesty of her foreign policy rhetoric.

Plibersek’s seems determined to discuss Iran with an eye to appeasing the Israeli government, the Washington government, whilst offering vaguely progressive signals. So on 11 March – four days before Plibersek claimed the ALP had “always said that we should engage with Iran” – Plibersek was asked “Are you comfortable with the Government’s diplomatic engagement with Iran?” She began by saying “Well I certainly think we need to have diplomatic engagement with countries right across the world, whether we agree with all of the things that their governments do or not.” So she was seemingly for engagement. And yet, she still criticised the Coalition for engaging with Iran:

“What amazes me is that the Foreign Minister has been so quick to welcome engagement with Iran, we suspect because she hopes that 9000 Iranian asylum seekers will be returned involuntarily to Iran if the relationship goes well. And so prepared to turn a blind eye to the anti-American rhetoric of the Iranian Government, the anti-Israeli rhetoric of the Iranian Government, to the human rights abuses, where people are locked up for their sexuality, for following a religion that’s not approved of by the regime, and most particularly, for political organisation against an oppressive Government. So yes, we understand that Iran is an important country in the region. We will need to work with Iran on issues like political settlement in Syria, but that does not give us the ability to turn a blind eye to those human rights abuses and to the continued sponsorship of the Iranian Government of conflicts in the region where they are funding and arming groups that are engaged in serious conflict in Yemen, in Syria, and in other countries across the region.”

In a way, this is more or less standard for a politician. Yet it displays an audacious cynicism. She is in favour of engagement with Iran, but complains about the Coalition engaging Iran. She says it is possible to engage with countries without agreeing with “all of the things that their governments do”. And then she slammed Bishop for engaging, because this seems to “turn a blind eye” to the evils of Iran. And those evils include “anti-Israeli rhetoric” and “anti-American rhetoric” – the kind of thing she used to traffic in, and perhaps even believe, not so long ago.

In a sense, this kind of language is obligatory. Both sides of politics show their concern for Israel, their devotion to the US, and pretend to care about human rights in oppressive countries that aren’t Western puppets. It is enough to note that though Plibersek commented on Iran supporting groups in Yemen, she has never commented on Saudi Arabia’s role in the destruction of Yemen, and seems unwilling to comment directly on the human rights record of the Saudi government (that interview is the closest I could come to the subject from her website).

Yet though both major parties offer rhetoric to show that they do not approve of Iranian foreign policy, Bishop has made engagement with Iran bipartisan wisdom. This is a positive development. It may be temporary. Given the cynicism of both parties, I suspect a policy of political engagement will depend on international relations, particularly the American relationship with Iran. Yet improved relations can create their own dynamic, especially considering the considerable economic interests vested in maintaining and expanding trade with Iran, explored below.

Iran may have a lousy and reactionary regime, which will one day hopefully vanish from the page of time. Yet there is no reason to believe that Western threats or attempts to interfere in Iranian politics will produce any positive outcomes. In April 2015, Iranian dissident Akbar Ganji observed that Iranians can’t “create a peaceful democracy in the shadow and threat of war.” Ganji explained that “When a nation such as Iran is threatened by the US and Israel for over two decades, and suffers from the most crippling economic sanctions in history, democracy becomes an impossible dream for its people, who live instead in terror and fear of war.” Ganji concluded that “If western nations are truly interested in the development of democracy in Iran, they should set aside military threats and economic sanctions.”

Yes, we should.

The Question Of Trade

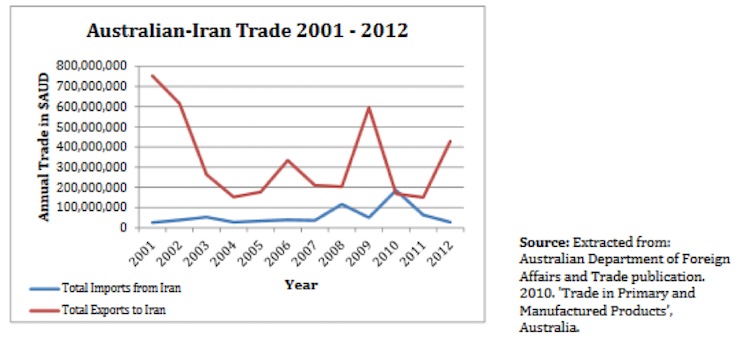

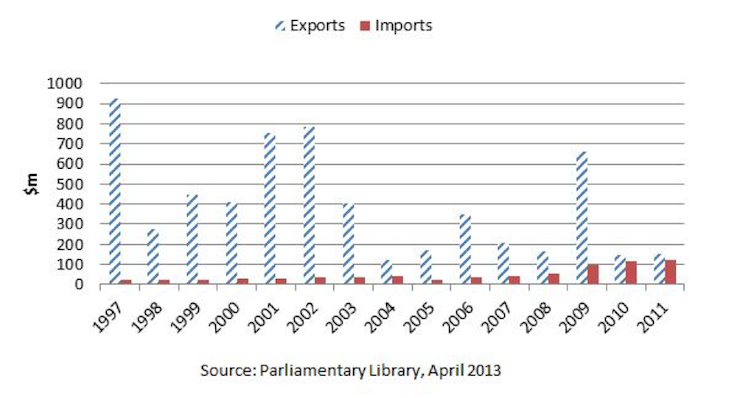

Traditionally, Australia has had good relations with Iran, and this is because we have had substantial economic interests invested in the relationship. Julie Bishop expressed strong interest in trading with Iran, explaining last year that “Prior to the sanctions our exports to Iran peaked at around $1 billion, now exports are currently valued at $360 million, so there’s clearly room to increase our trade with Iran, should sanctions be lifted.” Australia now plans to reopen a trade office in Iran, which it closed in 2010. The Trade Minister’s spokesman said Australia will “establish a permanent presence within the Australian Embassy in Tehran from the second half of 2016”.

The Trade Minister said that the removed sanctions has “created opportunities for Australian business in areas we excel: mining equipment, technology and services sectors and the supply of our agricultural commodities such as barley and wheat… Austrade has also identified opportunities for commercial co-operation in the health and medical and education and skills training sectors.” That is, there are lots of commercial reasons to get detach ourselves from political grievances between Iran, Israel and the US

Traditionally, this is what Australia has done. Professor Shahram Akbarzadeh, an expert in Middle Eastern politics, reviewed Australian-Iranian relations in a paper in 2013. He explained that “Historically, Australia maintained a bipartisan consensus on keeping trade with Iran separate from other political considerations. Bilateral trade suffered a temporary slump in 1980-81 as a result of the hostage taking crisis when 52 US embassy staff in Tehran were held hostage for 444 days. However, with the release of the hostages, Australia resumed full trade relations with Iran. In the course of 1980s, Iran grew to become Australia’s number one export destination in the Middle East.” Our “main items of export were wheat, meat and coal.” These were unaffected by the Iran-Iraq war, or the fatwa issued by Ayatollah Khomeini calling for the murder of Salman Rushdie and those associated with Satanic Verses.

This bipartisan wisdom was repeatedly expressed by politicians from both major parties. ALP Foreign Minister Gareth Evans claimed Australia had more leverage over Iran because of our trade with it. Coalition Deputy Prime Minister Tim Fischer said Australia keeps trade separate from geopolitics. Ian MacFarlane, most recently Minister for Industry under Abbott, and formerly President of the Queensland GrainGrowers Association, said “Iran is a market worth up to 500 million dollars (400 million US) a year to us, and it’s one which we don’t want endangered by politicking and by trade sanctions.”

This changed after Kevin Rudd was elected Prime Minister in 2007. Professor Akbarzadeh argued that it was in pursuit of a seat on the UN Security Council that Australia imposed sanctions on Iran in 2008. These were imposed on “on 20 Iranian individuals and 18 companies, suspected of contributing to Iran’s nuclear program in breach of its international obligations. The list included two major Iranian banks”. The sanctions were expanded every year from 2010 to 2013. The sanctions regime didn’t include wheat and meat, our “key items” of export. Other factors contributed to the fluctuations in our trade with Iran, including the “drought experienced in Australia in the first have of the 2000s”, and the “weakness of Australian industries to grow sufficient volume for export”, and the rise of Australian currency “in relation to the US dollar and the European Euro”.

A parliamentary library paper from 2013 observed that

“Over the past year, the Australian Government opted to widen the scope of Australia’s domestic sanctions against Iran whilst seeking to reduce Australia’s reliance on Iranian oil and gas resources. As the graph below indicates, while imports from Iran declined from $121 million in 2011 to $64 million in 2012, exports to Iran in the same period rose from $157 million to $205 million…. In 2010, Australia was Iran’s 28th principal export destination, and Iran was Australia’s 39th principal import source.”

Ultimately, our government has eagerly traded with Iran, above all seeking to export Australian goods to Iranian markets. Considering the hundreds of millions of dollars involved, these industries undoubtedly exert substantial pressure on the Australian government to limit political fallout between the two countries.

Julie Bishop has claimed that “in accordance with the UN Security Council resolution 2231, a number of sanctions have been lifted from Iran, and Australia has also lifted sanctions in accordance with the UN obligations, and this opens the way for there to be greater trade and investment between Australia and Iran”. It is possible that this will happen, but as we have seen, Australia never really cut off trade with Iran. As the graph above shows, exports to Iran spiked in 2009 and 2012, after sanctions were imposed, and then tightened.

So is trade with Iran going to shoot up? Perhaps, but if so, it would probably have done so regardless of Australia’s sanctions. It seems more likely that Australia cooled relations with Iran under pressure from the US, in exchange for American backing on the Security Council. Sanctions were more about signalling our alignment with the US than about ending trade relations with Iran. Yet the fact that so much money is at stake in our relationship with Iran is hopeful. However, hawks on Iran dominate corporate media discussion of the subject, our extensive trade with Iran produced enough material interest for Australia’s relationship to mostly withstand fluctuations in international affairs since 1979.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.