The Hodgman Government has appealed against a court decision banning it from allowing the activity, despite a Judge finding it would have a significant impact on a coastal area boasting a range of cultural treasures. Thom Mitchell reports.

The Tasmanian Government is going in to bat for four-wheel driving enthusiasts who want to motor over Aboriginal heritage sites, announcing yesterday that it will appeal a Federal Court decision which upheld a ban on the controversial pastime.

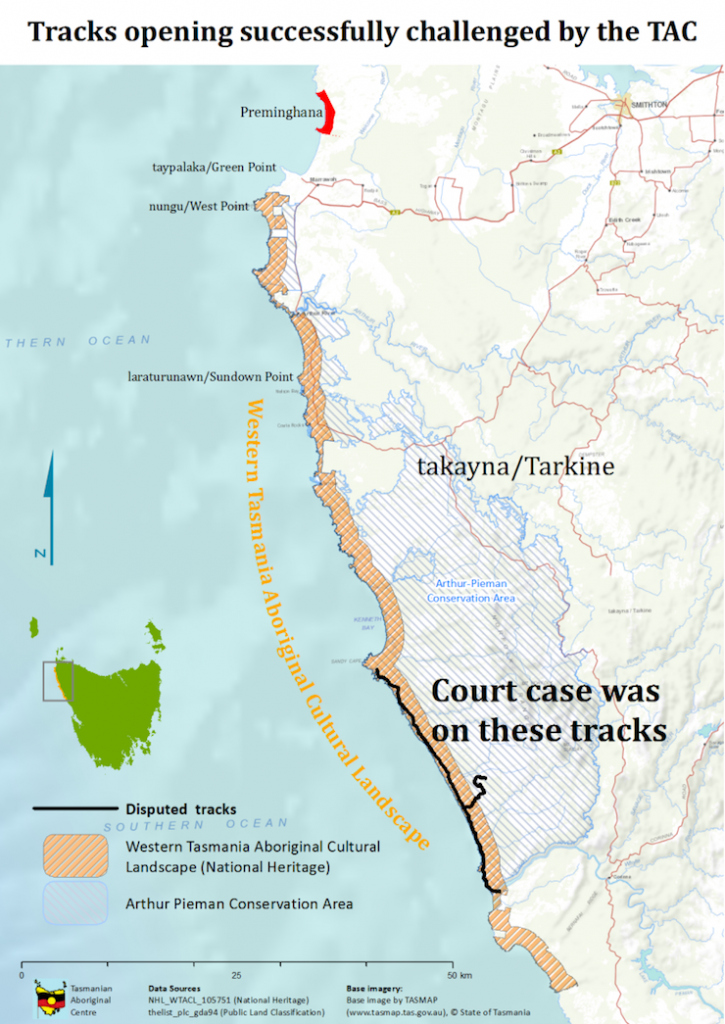

A two kilometre stretch inland of the state’s west coast, between Sandy Cape and the Pieman River, has been off limits to four-wheel drivers since three tracks were closed by the Labor-Greens government in 2012.

The area is of great cultural importance to Aboriginal Tasmanians, and is spread thick with middens, hut depressions, rock art, petroglyphs, and other sites of cultural importance. But four-wheel drivers in the state’s west are angry that they’ve been blocked from quite literally driving over the top of these Aboriginal sites.

Earlier this month a Federal Court recognised the area’s importance, and ruled it should be kept off limits to four-wheel driving, which Justice Debra Mortimer ruled would have a significant impact on Aboriginal culture.

Yesterday, Will Hodgman’s Liberal Government announced it would appeal that judgement.

Heather Sculthorpe, the Chief Executive Officer of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre, told New Matilda the decision to appeal the decision was ridiculous.

“We think it’s dismal and depressing and dismaying that they’re doing this,” she said. “It seems absolutely absurd to us, because they’re reacting to a handful of people who are pressuring them for political reasons, who seem to think it’s a popularity contest rather than a matter of law and evidence.”

“Justice Mortimer took a couple of months to form her opinion…and the most we can get from those who are objecting is ‘some people in the area don’t agree’, which is absolutely ridiculous.”

Sculthorpe said the government’s appeal is “irresponsible, and a bad use of money”.

“They got costs awarded against them in the Federal Court, now they’re trying to price us out of the market. If we lose we’re stuffed, they can potentially close our organisation,” she noted.

The area in question is known as the Western Tasmania Aboriginal Cultural Landscape, and Justice Mortimer found reopening the four-wheel drive tracks would be likely to have a “significant impact” on Aboriginal culture and heritage in the strip.

“There has already been a significant impact [from past four-wheel driving]and that’ll just continue,” said Caleb Pedder, an Aboriginal Heritage Officer of 26 years who has worked for state and Federal governments, as well as the Tasmania Aboriginal Centre.

“It’s one of the most densely populated areas for Aboriginal heritage in Tasmania,” Pedder said.

“You could get around some of the sites but you’d probably have hundreds you’d have to go over,” he said. “All up if you measure the linear length of it and measure them all together there’s about six and a half kilometres of sites together.”

Pedder has been involved in a number of surveys of the tracks, but he said “looking at just tracks is not sufficient” because there’s no practical way to prevent four-wheel drivers veering off track, and onto other sites.

He said the extent of the impact varies depending on which part of the coast you’re on, but “its basically open slather” on large portions of the coast because it’s actually a sand dune system.

“There’s a lot of Aboriginal Heritage in the dune system,” Pedder said. “Basically there’s no constraints on where the vehicles go down there, so they just drive over the whole area. If they hit a soft patch they’ll just head for a hard patch, which is the middens.”

On another stretch of coastline, “There’s sections where you have to manoeuvre through rock outcrops and stuff and at one of those outcrops you have to go past, there’s actually a rock art site metres from where the vehicles have to go”.

The Hodgman government had promised to invest $300,000 to protect sites which could be avoided, but Sculthorpe said that “is a sniff to what’s required,” and it’s not good enough that other areas would simply be sacrificed.

On some of the middens which can’t be avoided, the government has proposed to lay down matting to mitigate damage. “The judge spent a long time hearing evidence about that and she agreed with our evidence and our experts that it was not possible,” said Sculthorpe.

“It just indicates: One, they haven’t read the judgement; two, they have no idea what they’re talking about; and three, they have no heed for aboriginal heritage and protection of cultural sites,” she said. Pedder agreed laying down matting is “basically a waste of time”.

In fact, a key tenet of the judgement was that the whole cultural landscape must be protected.

“The value of the Western Tasmania Aboriginal Cultural Landscape is not to be found only in what can be seen at specific sites that have been identified through an incomplete survey,” Justice Mortimer ruled.

“The area has been recognised as having the value it does as an entire landscape: the whole of the area being identified as an area in which Aboriginal people lived, hunted, fished, traded and cared for their land in a way which was significantly more sedentary than the way of life adopted by Aboriginal people in other areas.

“[M]uch of the evidence concentrated on the likely physical impact of the driving of recreational vehicles over the three tracks, and on such matters as drivers deviating from the tracks and creating braiding. Such physical impact is not to be discounted or disregarded…

“But just as the desecration of a holy temple by the drawing of graffiti on one wall of the temple has a physical impact, so the impact on the significance of that temple to those who believe it to be sacred is not necessarily measured by the extent of the graffiti: it is measured by, at least in part, the effect of the act of desecration itself.

For its part the Tasmanian Government maintains it is “absolutely committed to providing access in a sensitive and appropriate manner”. In a statement released yesterday, Liberal MP Adam Brooks said “the delay in providing access as a result of the court action is very frustrating to the government, and to the broader community”.

“We will not give up, and the people of the Coast can be assured that we are in their corner,” he said.

“It is the Government’s view that in its judgement, the court erred in a number of areas relating both specifically to this case, and more broadly.”

According to the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre legal representative Jess Feehely, the Principle Lawyer at the Environmental Defenders Office Tasmania, the Hodgman government is “essentially seeking to re-agitate all of the key issues” of the initial legal bid.

The case centres on the interpretation of national environmental law, the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act, because the area of coastline in question was added to the National Heritage List by the former Federal Labor government in 2013.

Former Greens leader Bob Brown also weighed in on the growing conflict to suggest Will Hodgman “has shed his veneer of respectability as guardian of Tasmania’s heritage”.

“This appeal is more to red-neckery than to the Federal Court,” he said.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.