It’s International Women’s Day, but Australia is slipping on key measures of gender equality, with the pay gap blowing out in recent years. Max Chalmers reports.

Inequalities in pay and conditions from childhood to retirement – including a pay gap in pocket money rates – have seen a worsening in the gender pay gap in Australia, according to data highlighted by a new report from the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU).

The report, released to coincide with International Women’s Day, draws on previous research on gender inequality in the workplace and data compiled by the Australian Bureau of Statistics to paint a bleak picture, finding women now constitute 42 per cent of the workforce but currently earn 17.2 per cent less than men.

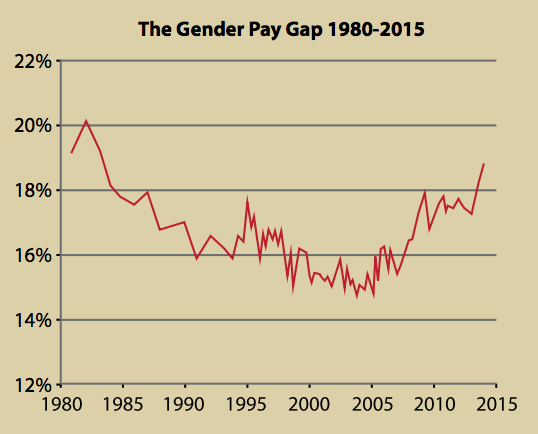

Despite this gap closing since the 1980s Australia has gone backwards in recent years, with the difference dropping below 15 per cent in 2004 before rising back to 18.8 per cent in 2015 then easing to the current rate in 2016.

“As a result women are earning less on average compared to men than they were 20 years ago,” the ACTU report notes.

These results have contributed to Australia plummeting in World Economic Forum’s annual Global Gender Gap Index, falling from a rank of 15 in 2006 to come in at 36 last year, behind countries including the United States, the UK, the Philippines, Namibia, and Mozambique.

The ACTU report highlights the levels of disparity still experienced by women in Australia across their lives, pointing to a survey that found girls receive 11 per cent less pocket money than boys, and evidence that more than one third of single women will retire into poverty. A 25-year-old man with a bachelor’s degree can expect to earn 1.7 times the amount a woman with the equivalent qualification will across his life, a difference of over $1.5 million.

In the time in-between things are no better, with women spending twice as much time performing unpaid labour including childcare, and the total pay gap for 35-44 year olds – including bonuses, overtime, and part-time income – sitting at an astounding 40 per cent.

This is despite an ongoing increase in workforce participation and education qualifications among women. Since 1987, women have graduated universities in higher numbers than men and a higher percentage of women now hold an undergraduate degree.

ACTU President Ged Kearney told New Matilda it was difficult to isolate the reason for the pay gap blowout, but that overt discrimination had clearly been replaced by indirect or covert discrimination.

“This is much harder to tackle. Organisations tend to assume that if they’re not consciously discriminating against women just because their conditions have worsened,” Kearney said. “Research shows that gender pay gaps is a problem in virtually every organisation due to the impact of unconscious bias on recruitment, training and promotion of women.”

That conclusion is bolstered by evidence that, while disruptions to work are a factor, men and woman in comparable situations continue to earn at different rates.

“The gender earnings gap cannot be simply equated to women choosing to have children,” Meg Smith, Director of Academic Programs at the University of Western Sydney, noted last year. “Relevant here is the evidence of a persistent gender pay gap among graduates in their 20s, a period that predates career interruptions due to child care.”

2009 NATSEM research found the biggest cause of the pay gap was “simply being a woman”.

“Consistent with results from other Australian studies it highlights the considerable impact that discrimination and other differences between men and women, including differing motivations and preferences, can have on reducing the earnings of women relative to men, irrespective of similar labour force and work-related characteristics,” the report said.

The ACTU is calling for a number of policy changes to address the issues highlighted in its report, including an increase in paid parental leave from 18 to 26 weeks and 15 hours of free childcare per child per week.

Kearney said the pay gap was leaving women less financially secure, forcing them to work longer hours for the same standard of living.

“Women continue to experience sexual harassment, bullying and discrimination at work,” Kearney said. “They face difficult choices when it comes to juggling work and family and in many cases are forced to compromise on one or the other.”

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.