Aboriginal activists, thinkers, and writers walk a fine line. Advocate too strongly and you face exclusion, compromise too often and you’ll still end up with nothing. If Stan Grant goes to Canberra avoiding the latter will be his greatest challenge, writes Amy McQuire.

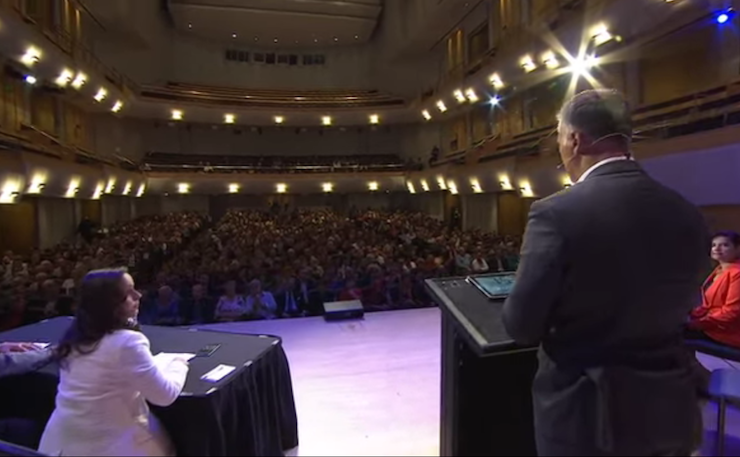

Just before Invasion Day this year, Wiradjuri journalist Stan Grant went viral. A speech he gave in the closing days of 2015, where he outlined how racism has been the foundation of the ‘Australian Dream’ and appealed to the audience that “we are better than that”, was hailed as “explosive” and “powerful”. The Sydney Morning Herald even pondered whether it was “Australia’s Martin Luther King moment” and said it had been “labelled our greatest against racism.”

The speech was delivered eloquently, off the cuff, and from the heart. It rightly tied the heartache felt by every Aboriginal person today to the destruction and dispossession of our peoples in every generation – from colonisation, to assimilation.

But it was nothing new. It was the uncomfortable truth that has been voiced time and time again by many Aboriginal people who have devoted their lives to fighting for justice.

It was a fact that even Grant acknowledged in the Guardian Australia, stating “other Indigenous people have delivered speeches similar to mine, frankly more courageous and enlightening.”

Grant is obviously a powerful advocate for our people, and he is also widely respected and admired across Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

He is an asset to the cause in many ways and it is inspiring to have an Aboriginal journalist, and one working directly in Aboriginal media, celebrated in major newspapers and networks.

The reaction to his speech, the thought that maybe Australians are “better than this”, also gives strength to many blackfellas who are constantly beaten down and belittled, who unlike Grant, are not celebrated by white Australia, but instead demonised for their truth and advocacy.

But the height of the fever-pitch around Grant, the numerous platitudes, the push for Grant to now consider a political career off the back of a couple of speeches, says more about the state of the nation than anything he has uttered so far.

Grant’s speech was great, but it was his eloquence, his position as an award-winning journalist, and his non-threatening diplomacy, that laid the foundation for this overwhelming enthusiasm from white Australia.

The white reaction to Grant says a lot about the messengers Australia chooses to listen to, and the ones it so ardently tries to ignore. I wonder if a speech from people like Pat O’Shane, or Gary Foley, or Tiga Bayles, would ever provoke the same reaction?

The enthusiasm is akin to that which greets anything uttered by Noel Pearson, ironically the last Aboriginal man to be compared to Martin Luther King jnr. They are unthreatening for white Australia. They are diplomatic.

Australia wants a diplomat, and Grant sees himself as one. He said in a recent extract of his book ‘Talking to My Country’, that he is no longer the “angry student of my youth”.

“I suppose I am a diplomat by nature; I seek equilibrium and balance…. More than that there is harsh pragmatism; we are only a fraction of this country’s population and if we can’t speak to the country as a whole than I fear we are doomed,” he wrote.

That diplomacy is seen in some of his commentary, like that on Australia Day; while acknowledging the hurt and pain felt by blackfellas on the ‘day of mourning’, he also sees room for recognition of “what makes (Australians) great and what that greatness demands of us”. None of this is exactly ground-breaking, or even controversial for Australia. It does not unsettle white Australia, in fact it comforts them.

Australia wants to feel comfortable about a celebration on Australia Day by acknowledging the history but not challenging it. In the same way, it wants to feel a little bit better about the racism that is at the foundation of this country, by acknowledging it, but not challenging it. By believing that Australians are “better than this”, when all the facts say we are not.

Eradicating racism is about much more than supporting a bridge walk or an apology, much more than saying you are committed to voting for a fluffy, meaningless preamble in a constitution.

To eradicate racism we must break it down within the structures that act as strongholds for white Australian privilege and prosperity. This is much more controversial because it implies Australia’s complicity in this racism when they really want to believe they are “better than this”.

We all have different tactics in the continuing struggle for Aboriginal rights but this diplomacy often doesn’t work, even for conservative leaders, who like Grant (who is slightly more left-leaning), provoke similar reactions from White Australia.

Just ask Pearson, the most influential Aboriginal man in the country.

You could argue Pearson is not particularly diplomatic in his tactics, but the rivers of government funding he has attracted for his Cape York trials, which has so far failed to produce a solid evidence-base to justify the expenditure, is in some part due to his willingness to tell white Australia what it wants to hear. For telling white government what it wants to hear. For making white Australia feel a little bit comfortable. And even that doesn’t work all the time.

Pearson last year expressed his frustration at his inability to make inroads on his favoured path of constitutional reform and on progress on his ‘Empowered Communities plan’. Pearson said that one of his biggest regrets was that he never pursued a political career.

“I made the wrong turn because I think I’ve hit the limit of how much influence you can have barking from the outside,” he said. If Pearson, a man hailed by white Australia as black Australia’s saviour, can’t make inroads, then what hope is there for Aboriginal people who refuse to toe that line?

Even from the inside, conservatives who are overwhelmingly supported by white Australia find themselves limited by what they can achieve. Just ask Bess Price who, despite winning platitudes from white Australia, still was refused the right to speak Warlpiri, her traditional language, in NT Parliament. In fact, she was reprimanded for it, warned that if she continued she would be ruled ‘disorderly’. Australia is happy to accept and promote Price, as long as she is speaking their language.

This diplomacy also overshadows those who often don’t speak that language – the ‘angry’, ‘unacceptable’ radicals who speak the truth and too often are derided for doing so.

It is not Grant’s fault – his advocacy is welcome and his eloquence is an asset. But his reception at the expense of other ignored black voices says more about the nature of Australian racism than any of speech he has delivered so far.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.