The United Nations top climate change bureaucrat has conceded the Paris climate talks will not keep global warming below two degrees, but agreed a price on carbon is the best way to not quite get there. Thom Mitchell reports.

The French Foreign Minister Laurant Fabius has emphasised the importance of pricing carbon at a press conference in Paris overnight after he officially ‘handed over the keys’ to a sprawling conference centre on the outskirts of the French capital to the United Nations’ top bureaucrat on climate change, Christiana Figueres.

World leaders are jetting in to Paris ahead of a planned ‘leaders event’ slated for Monday, where Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull will join with 150 other heads of state or government in delivering a speech to kick off the two weeks of negotiations geared at securing a legally binding treaty to limit global warming to less than two degrees celsius.

Fabius will also become the President of the conference, known as COP21, on Monday, and at a press conference in the suburb of Le Bourget, he was asked if he expected a price on carbon to form part of the new agreement on climate change.

Expecting a single price on carbon would be “perhaps be a bit utopic,” he said, but the former French Prime Minister argued that attaching a price signal to carbon emissions is crucial to cutting them.

“If we wish to move towards a low or de-carbonised world where we can have sustainable development, you’ve got to have… a price for the carbon, where it has a cost, and you also have to make sure that renewable energies are cheaper,” he told media.

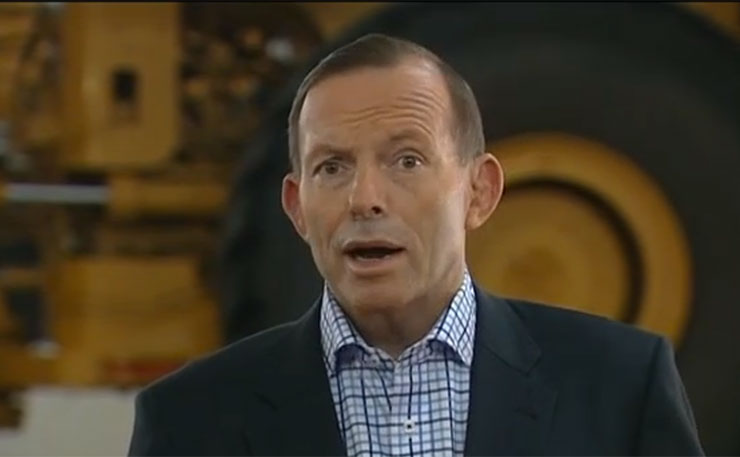

The comment may prove uncomfortable for Australia’s negotiating team, which will need to explain to the international community why, under former Prime Minister Tony Abbott, a tax on carbon was repealed and the national Renewable Energy Target slashed.

After executing a leadership coup in September, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has maintained the Abbott-era policies, despite the fact he called what is now Australia’s cornerstone emissions reductions policy “bullshit” after his support for an emissions trading scheme lost him the Liberal leadership in 2009.

The policy does not send an economy-wide price signal; instead the government has been inviting companies to bid for a share in the billions of taxpayers dollars it plans to pay out to firms which agree to mitigate their carbon emissions in the years to 2020 and beyond.

While Fabius and Figueres stressed the importance of allowing individual nations to develop their own means of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the French Foreign Minister made it clear that to his mind, some mechanism to price carbon is “obviously the right way to go”.

“There will be very strong initial statements [at the conference]to stress how important it is to move towards carbon pricing in as many countries as possible, and these initiatives will be carried by governments but also by businesses and companies,” Fabius said.

“I think it would perhaps be a bit utopic to think that in the agreement which I hope we are going to reach, that we will be able to fix a single carbon price. [But] I hope this price will be mentioned or the idea of a carbon price will be mentioned,” he said.

Australia is also in conflict with the World Bank, which has recommended carbon pricing as the most effective means of reducing emissions, and we remain the only nation on earth to actually repeal a price on carbon.

With negotiations almost underway in Paris, 183 countries have now put forward their commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and in most cases the policies they intend to use, and Fabius said they cover 95 per cent of the global total.

It’s an important departure from the process followed in previous talks in Copenhagen, in 2009, where countries’ commitments were thrashed out during the conference in extremely heated political circumstances.

Figueres said the change in process represents a strengthened foundation for achieving a deal, which Copenhagen was widely seen as having failed to do, and that the pre-conference commitments were “the first very concrete success of COP21”.

But she cautioned that the Paris pact will not be enough keep the rise in average global temperatures to less than two degrees above pre-industrial levels, which is the benchmark set out in the Copenhagen accord.

“With the full implementation of the national climate change plans on the table, we would be at a temperature increase that is anywhere between 2.7 and 3.5 degrees depending on what you’re counting and what your methodology and assumptions are,” she said

While it’s a vast improvement on the 4 to 6 degree catastrophe the world was headed for without international cooperative action on climate change, Figueres conceded it’s “not enough”.

“We know we have to actually be in the bandwidth of 1.5 to below 2 degrees…[and]that is why the Paris agreement needs to do the second very important task and chart the path of a continual decrease in emissions until we get the task done,” she said.

“We will not be hitting the two degree outcome at this conference for a very simple reason: The reference year that is used for temperature increase is not 2015, it is 2100. So what is very important here is to make sure that we affirm and increase the turning point that we have already seen occur.”

Fabius nominated funding for developing world adaptation to climate impacts already locked in, the split between developed and developing world responsibility for tackling global warming, and revision mechanisms which would aim to ratchet up the level of ambition periodically as key sticking points to be worked through by negotiators.

There is a sense of excitement and hope at the conference centre in Le Bourget, though, which Figueres and Fabius were keen to amplify in their first press conference as part of the talks.

“Before [it]was thought that addressing climate change was going to be only a burden,” Figueres said. “Now, over time, and particularly in the past year, it has been shown that we do not need to choose between economic development, between security, and between addressing climate change, but that these things go hand in hand.

“We are actually setting a much firmer foundation.”

* New Matilda environment writer Thom Mitchell is covering the COP21 talks in Paris, courtesy of the generosity of our readers and supporters who backed a crowdsource campaign to get him there. We have another crowdsourcing campaign running which is seeking to employ an Aboriginal cadet in our newsroom from March 2016. Click here for details – we really need reader support.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.