Labor’s efforts to attack Malcolm Turnbull’s wealth and Cayman investments may have been received poorly by the media, but they’re right to pursue him for it, argues Ben Eltham.

Should the personal finances of the leader of Australia’s elected government be a proper matter for political debate? What about the Prime Minister’s tax arrangements? Is it fair game to pursue a political leader for the disclosure of his or her tax records?

The Labor Party clearly thinks so. Late last week, Labor launched a full-frontal assault on Malcolm Turnbull’s tax arrangements.

In the Senate, Sam Dastyari gave an incendiary speech about Turnbull’s tax arrangements.

“There is one reason people invest in the Cayman Islands – so they don’t have to play by the same rules as the rest of us,” Senator Dastyari declaimed.

“Every time the Liberal Party votes against tax transparency, remember there is [a]house in the Cayman Islands — a house where Malcolm’s money resides.” Labor followed up with questions in the House.

Turnbull batted them away with ease, contemptuously taunting Labor about its tactics. The Fairfax papers weighed in, slamming Labor for its craven “class war” and ridiculing the Opposition for the “lame” tactic. Much of the commentariat nodded in agreement.

By the weekend, the whole thing has bombed so badly that Labor’s Tony Burke was wheeled out to defend the legitimacy of the attack. It all looked contrived, even desperate.

That’s a shame, because we need to talk about Malcolm Turnbull’s wealth.

Does it matter that the Prime Minister of Australia is a multi-millionaire, with a household wealth in excess of $100 million?

Yes, it does. It matters very greatly. The personal finances of the Prime Minister are, by any normal standard of democratic discourse, a legitimate topic of debate.

Malcolm Turnbull is not just one of the “1 per cent”, an admittedly partisan term. He is a proud member of the “0.1 per cent”. Perhaps a better phrase would be the old Edwardian term, “the upper 10,000.” Australia’s 29th Prime Minister is, quite simply, filthy rich. He lives in a mansion on Sydney Harbour. He need not work another day in his life.

The reluctance to question Turnbull’s finances is strange. Just three years ago, the media was enthusiastic in its support of the Coalition’s assault on Julia Gillard’s character, and her personal conduct as a solicitor two decades before taking office. Similar interest has been shown in Bill Shorten’s years as a trade union boss.

Nothing like that sort of interest has been shown in Malcolm Turnbull’s checkered past as a businessman and politician. Not to put too fine a point on things, it’s been a bit of a love-in.

Now, apparently, it’s out of bounds to question Turnbull on his personal finances. That’s rather inconsistent with the media’s typical views on the need to ask questions of elected officials. It may not be good politics to attack Turnbull because of his wealth. But that is an entirely different proposition to the argument that Turnbull’s wealth shouldn’t be a topic of debate.

The underlying squeamishness here is class.

Class is the great unmentionable in Australian political debate. In the prevailing atmosphere of “have a go” aspirationalism, we’re meant to applaud Malcolm Turnbull for his material success, and his desire to serve his country when he could be doing whatever he likes.

All governments push an ideological agenda, both subtle and overt. It’s not surprising we’re starting hear a lot about the value of “agile” entrepreneurs and tech wizards – businesspeople whose vision for society is often brutal and Darwinian. Malcolm Turnbull made most of his money with an early play in the Australian tech sector.

But is that the sort of economy we want for Australia? Economic growth of this kind tends to concentrate wealth at the top, as the many billionaires in Silicon Valley can attest. It doesn’t necessarily create jobs – as taxi drivers and newspaper journalists suffering from economic “disruption” both know.

Malcolm Turnbull runs a representative government, but he is not very representative of the voters he rules. Only a tiny proportion of Liberal voters are anywhere near as wealthy as Malcolm Turnbull, let alone the broader electorate. Turnbull also has fantastic reserves of social and cultural capital.

Wealth does matter. We live in a capitalist democracy in which the possession of great wealth enables the wealthy to live lives of almost unparalleled luxury and ease.

The very rich are not like you and I. They have more money. Much more money. This wealth allows them live in a very different world. They don’t need good schools and health care provided by the government – they can buy their own at the highest price. Consequently, they have much less personal interest in supporting a functioning social democracy. None of this exactly rocket science, let’s admit.

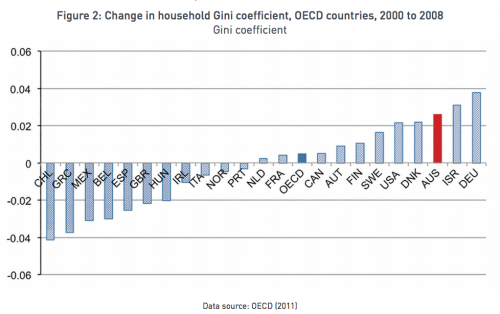

But not everyone enjoys such material comforts. Australia’s income inequality is above the OECD average, and it’s getting worse. The top ten per cent is pulling away from the rest of society, but the top 1 and 0.1 per cents are pulling away even faster. In this respect Australia is a case study of the income inequality observations made famous by Thomas Piketty.

Social mobility in Australia is stubbornly stagnant. Economic opportunity is not available to all. At the bottom, many people are doing it tough. Australia is a land in which poverty still stalks. An estimated one hundred thousand Australians are homeless, and perhaps a million of our fellow citizens don’t get enough to eat. A 2012 Anglicare survey found that seven per cent of the children surveyed told Anglicare that they went without food for a whole day, one day of the week.

How did the wealthy get so rich? The answer, increasingly, is that they started rich and got richer. The rich enjoy the advantages of talented accountants and tax lawyers, who can structure their financial affairs. One of the key strategies is the use of complex international money transfers to pay less, or even no tax. The erosion of national tax bases by the transfer of wealth out of a home jurisdiction is the core principle of tax havens like the Cayman Islands.

The argument that investing in tax havens is perfectly normal – it’s actually been made – illustrates why we need to have this debate.

It might be true that Australian super funds use international tax arbitrage as a matter of course. If it is true, this just underlines the scope of the problem confronting national tax regulators.

International tax havens like the Cayman Island are robbing ordinary taxpayers in two ways. Firstly, by allowing the richest to opt out of paying domestic taxes, they are forcing the burden of the nation-state onto those least able to pay it – ordinary wage earners. Second, tax shelters are a key mechanism for the wealthy to invest and grow their wealth while avoiding taxes, thus worsening economic inequality. This robs taxpayers by slowing the growth of real wages.

The idea that everyone should invest in a tax haven is the purest kind of neoliberalism. You cannot build roads, schools or hospitals if capital gains are spirited away to island jurisdictions.

None of this is to say that Malcolm Turnbull is undeserving of his wealth, or of his imperious social position atop Sydney’s upper crust. Nor am I saying Malcolm Turnbull will do the bidding of the elite to which he unquestionably belongs.

But it does matter that a man like this is Prime Minister. How could it not? To deny this is not to refrain from class war, but in fact to engage in it.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.