In 1989, Michael Jones, a solicitor in the NSW town of Gloucester, wrote a letter to the NSW Commissioner of Police, John Avery.

He was acting on the advice of Sydney senior counsel Greg Woods, now a District Court judge. Woods had become concerned after appearing for Jones’ client Roseanne Beckett (then Catt) in a bail hearing in Sydney.

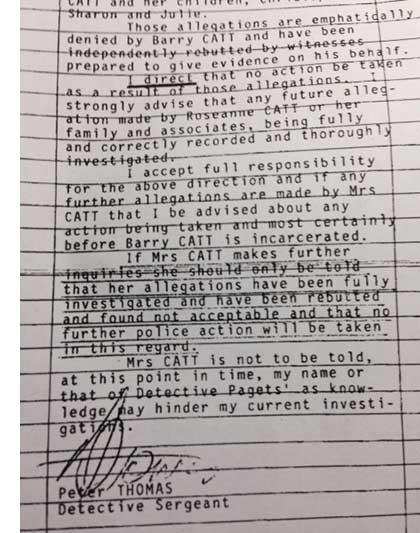

Roseanne had been charged with multiple offences after a police raid on her house led by a Newcastle Police Detective, Peter Thomas.

After the Supreme Court granted her bail, Thomas quietly arranged for her to be locked up again. She was released several days later after lawyers lodged a writ of habeus corpus (unlawful imprisonment).

Jones quoted the bail judge Justice Allen, who had expressed unease about the objectivity of Thomas and the weakness of the case against Roseanne.

Jones wrote, “A fair-minded observer might take the view that not only is the case against Mrs Catt not strong… but that it is a farrago of nonsense inspired by malice.” He asked for a fresh investigation of the case but warned the Commissioner that witnesses would treat fresh approaches from police with ‘fear, suspicion and mistrust’”.

“Detective Thomas… is conducting a vendetta against Mrs Catt,” Jones wrote. He put the Commissioner on notice of malicious prosecution proceedings against the police. He himself was threatened by Thomas and became a witness for the defence.

Jones warned: “This case is already a disgrace. It threatens to become a scandal.”

In fact the case of NSW v Catt (now Beckett) has always been a scandal. The fact that Roseanne served more than 3,500 days in prison and had to wait more than quarter of a century to be awarded $2.3 million damages in her malicious prosecution case against the State of NSW makes it a far bigger scandal.

From the day of her arrest, Roseanne has always maintained her innocence of an avalanche of charges that included perjury, possession of a gun and assault, soliciting to murder and attempting to poison her ex-husband, Barry Catt.

She was convicted of eight charges and sentenced to 12 years in prison in 1991. As a consequence, she and her family, especially her children, have suffered immense loss.

In 1989, Roseanne was an enterprising, hard-working, fun-loving woman of 42, caring for five young people. The charges caused her to lose her freedom, health, ability to earn an income, home and the affections of her step-children.

As Justice Ian Harrison put it in his decision earlier this week, “The enormity of this loss is made still more staggering by the significant period of time for which that loss was suffered.” Her son, Peter Bridge, has spent his entire adult life standing by her. For collateral damage such as this, there is no compensation.

NSW Internal Affairs documents show that even before Roseanne’s release in 2001, senior NSW police officers had reviewed the case and informed the then NSW Police Commissioner Ken Maroney that they had at least 12 serious concerns about the case, and considered that Roseanne might have been framed.

Yet since her release in 2001, Roseanne, her small group of dedicated supporters, and a shifting team of lawyers have undergone a lengthy and tense ordeal in their battle for a modicum of justice.

The NSW Office of Public Prosecutions during Roseanne’s criminal cases, and the Crown Solicitor’s Office, which defended the malicious prosecution case, have expended millions of dollars despite scarce public legal resources, resisting at every possible point.

The failure of NSW authorities to hold Peter Thomas responsible for his actions not only caused great damage to those involved in this case, but many others as well.

While still a NSW detective, Thomas was involved in a number of other frame-ups that had disastrous consequences for his accused, even those acquitted. Throughout his career fellow police, including more senior ones, failed to prevent his criminal and improper behaviour.

As his internal affairs file shows, Thomas had absconded drunk from an accident, assaulted people, improperly handled property and been found to have intimidated witnesses, well before he left the police force in 1991.

He was able to register as an arson investigator in Queensland where, working for insurance companies, he adopted a practice of falsely accusing people of burning down buildings.

ABC Four Corners and the Sydney Morning Herald exposed a number of these cases in 2000. Despite initial hope for a broad inquiry, to this reporter’s knowledge no action was taken in any of the other cases.

In 2002, then Greens MLC Lee Rhiannon argued in NSW Parliament:

“The New South Wales and Queensland governments should hold a joint inquiry into all cases in which Thomas played a role. These cases raise a number of important issues that need to be investigated by the Government so that reforms can be put in place….

“When an officer is found to have fabricated evidence against one accused person, what action is taken by the Crown to find out whether innocent people may be in prison because of corrupt activities by the same officer? How does the Government plan to compensate the victims of police corruption? We believe that these are most important issues.”

Rhiannon raised the case of Jake Sourian who was falsely charged by Thomas with burning down his service station.

Sourian was acquitted, but lost all his assets and was never compensated. To this day he suffers from the consequences of this injustice.

A corrupt bully who intimidated witnesses

Those familiar with the Roseanne Beckett saga were not surprised to learn this week that Roseanne’s barristers, Paul Blacket and Nicholas Broadbent, had succeeded in convincing Justice Harrison that Thomas was driven by malice to improperly use the legal system in his campaign against Roseanne.

Harrison accepted that Thomas was a corrupt bully who “intimidated witnesses with a view to getting them to give evidence or not, as the case may be, or to change their story if it did not suit Detective Thomas’s aims or interests.”

He found there were more than eight witnesses who had a story to tell about his “extraordinary and overbearing methods” and his “arrogant contempt that was intimidating and frightening for them”.

From many interviews with those involved in the case, I know that he instilled fear in many people that lasted until his death last year.

This is the man whose actions and evidence the Crown has spent massive legal resources defending for 26 years.

It’s more than a decade since Acting District Court Justice Tom Davidson conducted an inquiry into the case to establish facts for a fresh appeal. This was a much broader and more open-ended process than the recent malicious prosecution proceedings.

Judge Davidson found that Thomas may have planted a gun on Roseanne. And he found evidence that Barry Catt, Thomas, fellow detective Carl Paget and unemployed mechanic Adrian Newell, who was intimately involved in the case, may have framed Roseanne on a charge that she attempted to poison her husband’s drinks.

Judge Davidson found that while there was some evidence to support six other convictions, it was reasonably possible that the jury’s guilty verdicts were substantially influenced by the unreliable evidence of Thomas, Catt, Newell and Thomas’s police partner Carl Paget.

Despite his specific instructions that witnesses were not to contact each other while in the witness box, evidence was produced that the Crown witnesses stayed in contact through scores of phone calls. Davidson referred the evidence to then Police Commissioner Ken Maroney for consideration for proceedings against some of the Crown witnesses.

Despite police being in possession of evidence that Thomas had a tendency to intimidate witnesses or induce them to give false evidence, no further action was taken.

Davidson also questioned Thomas about false information he had fed to a journalist, and then lied about in court. The judge forwarded this information to the DPP for consideration of perjury, but despite clear-cut evidence, still no action was taken.

The Davidson inquiry report went back to the Court of Criminal Appeal. Astonishingly, Wayne Roser, who represented the Crown at both the Inquiry and the Appeal hearing, simply rejected the inquiry findings and continued to argue that Roseanne was guilty of all charges.

The NSW Court of Criminal Appeal acquitted her of one charge, dismissed five more charges and maintained two convictions.

Ex-MP and solicitor Peter Breen appealed to the then NSW Attorney General, Bob Debus to grant Roseanne an ex-gratia payment and investigate a successful NSW Victims Compensation claim of $89,000, paid to Barry Catt on the basis of false statements.

But rather than offering an ex-gratia payment that would have involved no admission of liability, the Crown forced Roseanne to take the difficult path of malicious prosecution proceedings.

Further time was wasted while she searched for legal assistance.

Eventually, the legal firm Turner Freeman agreed to act, and launched proceedings in 2008.

The Crown’s early tactics were ones of delay caused by lengthy contests aimed at resisting the plaintiff’s search for Police internal affairs files and other evidence held by the NSW government.

Relying on an old High Court ruling, the Crown also argued that because some charges had been dismissed rather than her being acquitted, Roseanne would have to prove her innocence.

The High Court overturned this old ruling in 2008. The proceedings ground slowly forward. It was not easy to find a judge with time to hear the case.

Finally in 2014, the trial took place during eight weeks of hearing days spread over nearly six months. Both sides were represented by senior counsel, two junior barristers, solicitors and assistants.

During the trial, the Crown’s tactic was to exclude as much damaging evidence as possible.

The final result was that Justice Harrison awarded Roseanne damages on two of six counts. It’s important to understand that despite not being a total victory, the verdict is still a huge win.

As Justice Harrison commented, the tort of malicious prosecution is notoriously hard to prove. He described Roseanne’s task as a “difficult one and the significance or relevance of her witnesses is often just as difficult to understand. That notwithstanding, it remains for me to form and to express views about them, and to extract if I can from their evidence the grains of insight that might illuminate the dark and fading past that holds the answer to this litigation.”

The odds aren’t in your favour

To win a malicious prosecution case, a plaintiff must clear two big hurdles. The first is malicious intent. In Roseanne’s case, this was the easy part of the case, as there was ample evidence that Thomas had intimidated Roseanne and at least eight other witnesses.

She also had to prove that in relation to each count, Thomas and his partner detective either did not have an honest belief in the guilt of the accused, or, if they did, there was no reasonable basis for that belief.

The task confronting Roseanne and the judge was made even more difficult by the Crown’s failure to call its three key prosecution witnesses – Thomas, Catt and Newell.

In the light of their evidence before Davidson, it was not hard to understand why they were not presented for cross-examination.

Thomas, who would have been questioned about lies he had previously told in other cases, died in 2014, before the end of the case. Catt died shortly afterwards.

Justice Harrison also criticised the Crown for flouting the earlier High Court judgement by unnecessarily calling one of Barry Catt’s now adult children. He described this decision as demonstrating “a flagrant disregard by the state for judicial authority in defence” of the claim.

Roseanne managed to prove she was maliciously prosecuted on counts of perjury and solicit to murder, both very serious charges.

The perjury charge may be unique in the history of the NSW criminal justice system. At the time of her arrest, Roseanne had charged her husband Barry Catt with assault. The proceedings were part heard. Thomas intimidated one of Catt’s witnesses into changing his story to align with Barry Catt’s version of events. He then cut through the existing proceedings, turning the tables on Roseanne by charging her with assault.

Without further investigation, and without following any proper procedures, Thomas and Paget then took the extraordinary step of charging her with perjury.

Roseanne’s son Peter Bridge (pictured below with Roseanne) broke down in the witness box as he recalled the terror he felt when Thomas held him at Taree police station while he threatened and pressured him to change sides in the assault case. He stood by his mother and was also charged with assault, but was later acquitted.

When Roseanne was released on bail, she was ordered to stay out of Taree. The local court proceedings floated off into a legal vacuum, never to be resumed.

The second charge involved the Aboriginal police liaison officer, James Morris who signed a statement against Roseanne the day after her arrest. The statement stated that Roseanne, who he had never met before, approached him at the local RSL club and asked him to “do a job on [her]husband” for $10,000 and “if you kill him, you’ll get a bonus.”

Morris, who was drunk at the time, was supported at the original trial by his sister, who said she thought it was “a joke.” Morris said that about a week later he bumped into Roseanne who repeated the offer. Morris and his sister made no report to police about these events at the time. Apart from these signed statements, Thomas carried out no other investigation.

Roseanne denied these incidents ever took place. Her case was that in July 1989, Morris was vulnerable to pressure from Thomas because he “was being investigated by FACS for alleged sexual conduct with a number of Aboriginal girls and that he knew Detective Thomas and Mr Catt prior to 28th July 1989.”

NSW Family and Community Services manager, Greg Baggs made a note in September 1989 about rumours concerning Aboriginal girls allegedly involved in sexual intercourse with Morris and other Taree police officers. The local Aboriginal community had allegedly known of these rumours and disclosures, which had been made to a local medical service.

There is no evidence that the allegations were true, or other evidence apart from Baggs’ report that they were ever made. In earlier proceedings, Roseanne’s lawyers attempted to subpoena files about this matter but no documents could be found.

Morris was a witness at the Davidson inquiry but had little memory of the events in 1989. The Crown failed to call him or his sister in the malicious prosecution case. Roseanne’s lawyers were unable to prove that Thomas had used the allegations to improperly pressure Morris into signing the statement.

Justice Harrison did find, however, that on the basis of such inadequate evidence, Thomas, who was an experienced detective, could not have formed and therefore lacked an honest belief in Roseanne’s guilt.

Harrison concluded, “It would surprise me to the point of astonishment if Detective Thomas had ever been presented with a more absurd complaint in the whole of his policing career to that point. It is difficult from my perspective to imagine a less credible or more unlikely set of facts upon which to base an honest belief in the guilt of anyone.”

The two counts on which Roseanne was successful raise two big questions.

The first is that if Harrison’s conclusions are correct, how could an experienced police prosecutor, senior officers from the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, and at least five Crown barristers, have so vigorously pursued her on these charges? Did the trial judge and several Court of Criminal Appeal judges feel comfortable with the guilty verdicts?

In 1991, a well respected Lismore Crown prosecutor, Nick Harrison drew the attention of senior Crown prosecutors to evidence that Thomas and another detective had intimidated a witness in another frame-up, and should be charged with perjury.

Instead of pursuing the matter, the DPP and Crown quietly settled a malicious prosecution case by the two accused and continued to present Thomas as a witness of truth. This reporter submitted questions to the NSW DPP as far back as 2000 that were never answered. It’s time for the DPP and Crown lawyers to account for their decisions.

The second question is what was really going on behind the scenes in Taree in 1989.

In a long report to the NSW Ombudsman in 1989, FACs officer Greg Baggs wrote, “There are many sinister activities associated with the motivation of many people surrounding Barry Catt’s children.” Lurking in the hundreds of court books and thousands of pages of evidence, there are glimpses of a frightening story including a mysterious murder, child abuse for which there was medical evidence, a child abuse worker threatened with rape for doing her job, allegations that police watched children perform sexual acts, sexual abuse of Aboriginal girls, another female victim of Barry Catt who found her animals dead after she gave evidence for Roseanne, and ex-prisoners who say they were offered inducements to assault Roseanne in prison.

While-ever Roseanne was the accused, the hints of “sinister activities” could always be regarded as irrelevancies at the periphery of the case.

Paediatrician Dr Sara Williams persistently raised her concerns about some of these matters with NSW police, senior law officers, the NSW Attorney General, the 1995 NSW Royal Commission into Police, and other bodies until she died several years ago.

She told me that when she visited Taree after Roseanne’s release she was advised by another medical practitioner that it would be dangerous to ask further questions about the possibility of an organised paedophile racket.

Twenty six years later, one hopes that in the light of recent attention on domestic violence and child abuse, those in authority might has asked more questions about Thomas’s vengeful hatred for Roseanne, his interference in the sexual assault charges against Catt, and looked more deeply into Bagg’s concerns.

The notion of Thomas as an ‘out of control’ detective may be true, but it doesn’t provide an explanation for why his actions were defended so vigorously.

Time is the Crown’s friend

Time works in favour of the Crown. A crucial witness for the plaintiff, Peter Caesar, an ex-business partner of Thomas who had fallen out with him, came forward after the Four Corners program Burned was broadcast in 2000.

He made a statement that Thomas had told him he had planted a gun. This became the ‘fresh evidence’ that allowed Roseanne to get a second appeal.

Justice Davidson found that although his credit was open to attack, his evidence was capable of being believed by a jury.

Despite being in extremely poor health, Caesar gave evidence again before Justice Harrison. To anyone who had seen him give evidence before, it was clear that he could no longer recall the chain of events that led him to come forward. No-one who watched his evidence would be surprised that Justice Harrison did not find him credible.

In fact, Caesar was not the only person who told journalists that Thomas had boasted he had framed Roseanne. But he was the only one who was prepared to be identified. Courts can only deal with the evidence before them, but that’s rarely the full story.

Reform needed for miscarriage of justice victims

We can be sure that amongst the thousands of prisoners who go to bed in Australian prisons tonight, there are other victims of a miscarriage of justice. But there is little chance of their cases garnering the attention they deserve unless a wrongly convicted person has strong personal and legal support.

The media also often plays a role in bringing cases to light. In the context of an expanding and under-resourced prison and legal aid system, and an under resourced media, it is extraordinarily difficult for victims of a miscarriage of justice to have their voices heard.

It’s important to understand that not only has this malicious prosecution judgment taken 26 years, but it might never have happened at all. By the time she had lost her first appeal, Roseanne and her family had exhausted their economic resources.

After she was imprisoned, Roseanne was portrayed by the media as the world’s most ‘evil and manipulative’ woman, and a treacherous stepmother. Then, as she battled to cope with her imprisonment, her case remained out of the public eye for about eight years, although many fellow prisoners and staff heard her story.

Hostile staff judged her claims of innocence to be evidence of her ‘evil and manipulative’ nature.

Roseanne would not have reached this point if she had not met several voluntary religious visitors to Mulawa Women’s prison, including Mary Court, an impressive Samoan Australian woman who has supported Roseanne for nearly 20 years.

Ex-primary school principal, Sister Claudette Palmer (pictured below) met Roseanne while she was a chaplain in Mulawa Women’s Prison. She believed Roseanne’s story and has regarded it as her mission to see that Roseanne achieves justice.

She was also fortunate that ABC Four Corners took a brief interest in her case and that the SMH pursued it for many years. Even so, there were times after her release when she found herself without legal help. A young barrister acting pro bono helped her draft her first appeal documents.

Finally, Roseanne got lucky when miscarriage of justice expert Tom Molomby represented her in the final stages of the Davidson Inquiry.

If this case attracts attention to the need to reform in the approach to miscarriages of justice in NSW, something will have been achieved.

In a recent speech, retired High Court judge Michael Kirby drew attention to the need for a body such as the UK Criminal Cases Review Committee, which has resources, time and expertise to re-examine chosen suspect cases.

But in the meantime, the NSW DPP and the Crown have questions to answer about the conduct of this case. It has been challenging to observe the denigration of Roseanne from some lawyers and journalists who knew nothing about the case.

Over the years, I would bump into acquaintances who were barristers and judges who would look uncomfortable when I said I was at court to cover the Roseanne Beckett story. Even last year, a senior counsel who knew almost nothing about her warned me that she was a horrible person.

It’s clearly more comfortable for some people to launch personal attacks on Roseanne, rather than face the injustice of her case.

As he left the court on Monday, I asked Crown Senior Counsel John Maconachie what he felt about the judgement. “It’s no different to any other case,” he said.

Perhaps that attitude is part of the problem. It’s one thing to argue that every litigant deserves to have his or her case argued. It’s another thing altogether to say that massive legal resources should be spent denying compensation to those who have suffered loss at the hands of corrupt, violent agents of the state.

The Crown is reported to be considering an appeal. Justice Harrison reminded them that it was 26 years to the day since Roseanne’s arrest. In a lengthy judgement, Crown lawyers may well find legal points to argue.

The state is supposed to act as a model litigant. This means lawyers acting for the State of NSW should act according to the highest standards of ethics and fairness.

If they become aware that the state has committed wrongs, those representing the state should advise the government to apologise and make at least partial amends.

Of course, this does not mean lawyers shouldn’t resist unreasonable claims or apply their skills to defeat opponents.

There are always lots of tactical options in court cases such as this one. Rather than an appeal, there needs to be an inquiry into how the Crown applies its resources.

Last year, NSW Crown Solicitor Ian Knight, who was the instructing solicitor in this case, admitted to multiple breaches of the model litigant policy during an appearance before the Royal Commission into Institutional child sexual abuse.

Junior Crown Counsel Patrick Saidi was briefly called away from the malicious prosecution trial to be questioned by the Royal Commission into Institutional Child Sexual Abuse about the way he handled a case involving several Aboriginal plaintiffs who sued the state of NSW for abuse suffered in the Bethcar home in Brewarrina in northern NSW.

He defended his approach to litigation, telling the Commissioner that he did not consider he had an obligation to provide opponents with all witness statements in his possession.

Greens Senator Lee Rhiannon (pictured above), who first met Roseanne in 1999 when she was a NSW MP on a parliamentary committee inquiring into women in prison, told Federal Parliament in 2013:

“It is clear that powerful institutions have wronged Roseanne Beckett. Continuing to hide the facts and delay restitution is unacceptable. Roseanne and her supporters for over a decade have been working to clear her name. What happened to Roseanne has not just affected her; it reflects poorly on all of us.

An inquiry is needed into the Crown’s behaviour in dealing with Roseanne. The New South Wales government should be held responsible for the injustice she has been subjected to.

It is time the government took responsibility for ensuring Roseanne is afforded justice and full compensation. A speedy and just resolution to this case is important for Roseanne, for all women and for our wider society.”

NSW needs a Criminal Law Review body that can consider cases like this one. But if one is established, it needs to include a woman with feminist perspectives on law and policing. A longer exploration of the role that gender stereotypes and misunderstandings about domestic violence have played in this case is needed, but it was interesting to note some messages of support from women this week.

A woman who was in prison with Roseanne nearly 20 years ago, and was one of those who came to believe her story, wrote to me this week telling me that Roseanne “had held her head high” and that she and other ex-prisoners wanted her to know that they were quietly having a few “wee ones” for her this week.

Congratulations also came from women on the NSW Mid North Coast area who have direct knowledge of the consequences of Barry Catt’s brutality.

After Roseanne went to prison, he was subject to several more restraining orders, caused serious injuries to at least one other woman, and imposed an extended period of terror on another.

More stories about the Roseanne Beckett case can be found on Wendy Bacon’s blog here.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.