It could so easily have come to nothing.

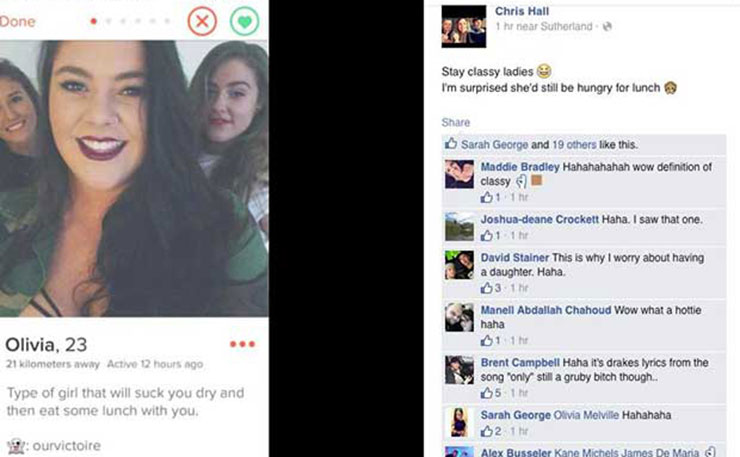

A man sees the profile of a young woman on Tinder, the ubiquitous dating app and theatre of digital matchmaking.

In the section of the woman’s profile left for biographical information, under a picture of her with two friends, is a quote.

“Type of girl that will suck you dry and then eat some lunch with you.”

Within a matter of hours these words had sparked a viral saga that spun off into a heated argument about sexism and threats of violence, drawing an ever-growing range of players eventually including the NSW police and a member of the Australian Senate.

The Tinder profile in question belonged to 23-year old Sydneysider Olivia Melville, but the words that set the fury in motion were not hers.

In one of the many ironies of what would follow, the quote was borrowed from Canadian child star turned international hip-hop goliath Drake, a reference to a line in his verse on ‘Only’, a global hit that notched 133 million views on YouTube.

When Drake delivers the line he’s describing what he likes in a lover, in terms of their sexual (and regular) appetite.

But with the words appropriated by a woman on a dating app, another Tinder user, a man named Chris Hall, thought he’d stumbled across something funny.

Hall took a screenshot of the profile and shared it from his personal Facebook page with a derogatory caption, targeting Olivia for what was perceived as a direct and open expression of sexual desire.

“Stay classy ladies. I’m surprised she’d still be hungry for lunch.”

Through a mutual friend, word got back to Olivia, and she soon saw the comments Chris’ friends had left, including the ones describing her as “a grubby bitch”.

Angered and upset, unable to comment on the thread, Olivia contacted Chris and retaliated by sharing his post from her own page so that her friends could see it.

“[Shout out] to boys posting your tinder profile on Facebook, I wasn’t aware I had to put my CV in my Tinder Bio apparently Drake lyrics aren’t ok,” she wrote.

“Shame on you Chris Hall for your ignorance of Drake & good taste.”

As Chris and Olivia messaged, Olivia’s friends started to react, infuriated their friend had been publicly shamed for using a line which, let’s not forget, was brought into the world by a man who performed it to millions of people around the globe without being publicly shamed.

In their interactions, Chris Hall started out polite, almost friendly in tone, perhaps a little nervous he had kicked off something he hadn’t meant to. He didn’t apologise. Instead he told Olivia that if she didn’t want to be judged she should change her Tinder bio or accept the criticism that it made her look like a “slut”.

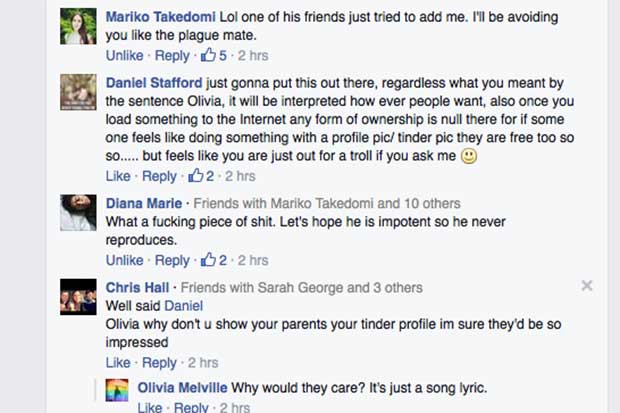

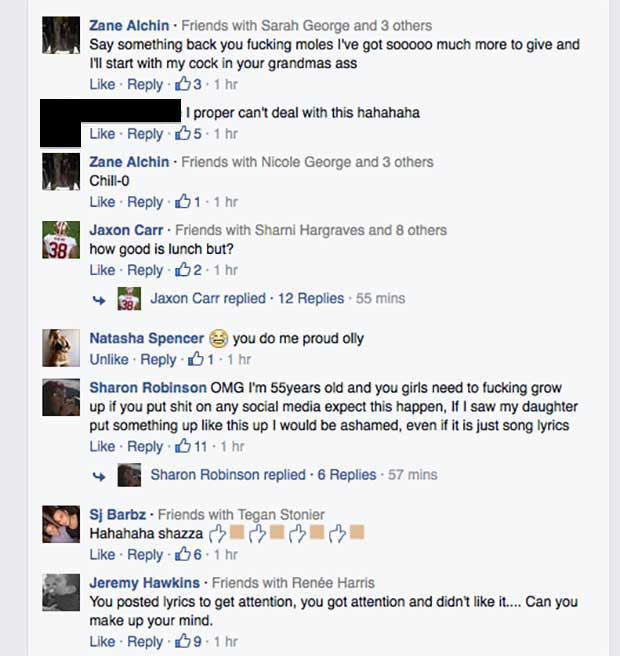

Fights started to break out under Olivia’s post as friends of Chris’ joined in.

It was clear this was about something bigger than social media courtesies and etiquette.

“You imply to be a slut, then you get upset once you’re called one. Haha,” wrote Jack Jesm, real name Jack Sweeney.

The people attacking Olivia – men and women – expressed dismay that a woman might publicly show interest in sex on a platform built largely to facilitate sexual encounters.

Regardless of whether that had been Olivia’s intention – or whether, in fact, as the Drake-themed background and Drake-themed screensaver on her phone suggest, she just really likes the Canadian rapper – her friends were infuriated by the sentiment. If she was being unironic in her deployment of the lyric what the hell was the problem anyway?

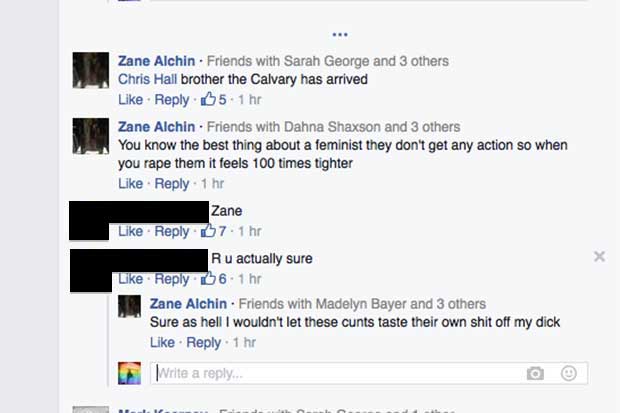

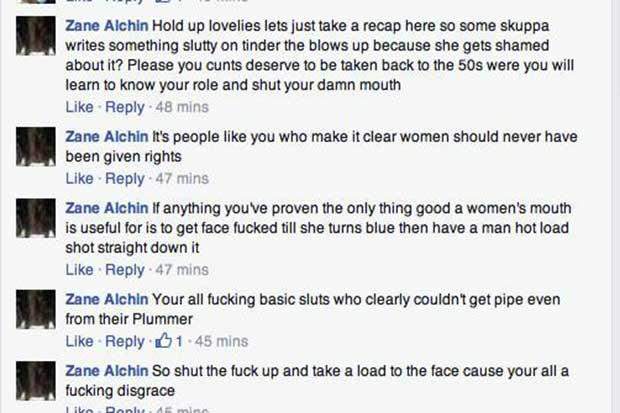

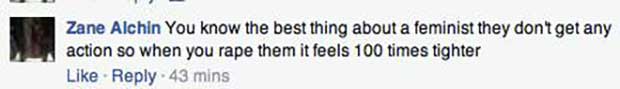

As they made their point, forcefully at times, the threats of sexual violence started.

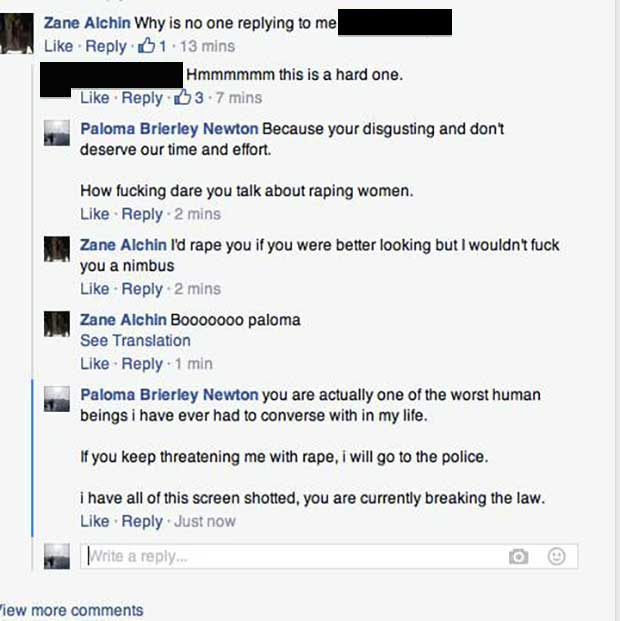

These ones came from one source in particular – Zale Alchin – but were specific and repeated, and they caused the next escalation.

One of Olivia’s friends, Paloma Brierley Newton, shared her own post with screenshots of the abuse. The post started to go around. It was eventually shared 522 times.

I want to take a moment to talk about sexual violence and harassment. Today a friend of mine became aware that someone…

Posted by Paloma Brierley Newton on Monday, 24 August 2015

It wasn’t cute cat video viral, but a petty and sexist joke at the expense of a woman not personally known to her ridiculer now was getting some pretty wide exposure.

It should be noted that Chris Hall did not endorse the extreme rape-related comments others had made and was now taking on personal attacks himself. As the blowback grew he deleted the original offending post on his own wall and eventually offered a private apology to Olivia.

It was too little as far as Olivia was concerned – she wanted a public apology – and it was definitely too late, as far as the rest of the internet cared. Digital wheels were in motion.

Feminist writer and Fairfax columnist Clementine Ford shared Paloma’s post, taking the shocking images of Zane Alchin’s violent threats to her audience of over 50,000 Facebook followers.

“This is what rape culture looks like,” Ford wrote. “This is what cyber sexual violence looks like. This is what a fucking creep who needs to be reported to the police looks like.”

This is also what happens to women who challenge sexism online. More sexism and, very likely, the rhetoric of sexual violence.

It’s reminiscent of the treatment of Muslim women’s and multicultural activist Mariam Veiszadeh, who gets sexism with a side order of pigs heads.

Ford’s followers knew the context.

Dr Emma Jane, a senior lecturer at the University of New South Wales, knows it too.

Dr Jane is in the middle of a three-year study assessing women’s experiences of harassment online and she’s seen the scenario many times before.

“I’ve been tracking this kind of discourse online since the late 90s,” she says.

“I didn’t realise that I was tracking it at the time, I was just collecting material that I was receiving via the internet while I was a journalist. Then as time passed, I noticed more and more women speaking out about receiving this kind of sexualised vitriol and realised I wasn’t the only one receiving it.”

Dr Jane says the messages were often so profane and disturbing that people were hesitant to share them publicly.

“Then there was a point in about 2011 when a large number of female commentators from all around the world started speaking out, sharing and republishing some of the private material they were receiving.

“One of the many striking things about these communications was all these messages looked really similar. They read like it was the same one guy abusing the same one woman. This is one of the reasons that I feel confident in saying that this is a gendered phenomenon.”

This is the context the young friends of Olivia Melville grew up with. They’re ‘digital natives’, and they came of age in an environment that has proved particularly hostile for women to explore.

Though he clearly had no idea of the past history, Chris Hall had become a focal point for their previous experiences, the most recent incarnation of that one same guy.

Zane Alchin, you suspect somewhat more knowingly, cast himself as the more insidious personification of that character.

And that’s part of the reason Paloma Brierley Newton did, in the end, take his threats to the police.

Paloma tells me later that it was the comments about her family that finally drove her to action.

“Raping our friends, raping our families, raping our mothers, our grandmothers, some pretty awful comments [went]around,” she says. “We decided to step back from that. We decided to stop replying and we decided to go to the police.”

With the decision made Paloma headed to Newtown Local Area Command with Sophy Jones, another friend of Olivia’s. It was a seven-minute drive to the station and their hands were shaking. They paused before entering the cop shop, a mix of nerves and adrenaline.

Clearly rattled, Paloma had hit out in the comment thread.

“If anyone fucks with my friends I will find you,” she wrote at one point.

Both women arrived at the station to report what they now believed had evolved into an actual crime perpetrated against them. They also wanted to make a point.

“I don’t think anybody is going to learn until you do start handing out punishments because until that point, people are just getting away with it, getting off scot-free, and it’s not good,” Sophy says days later.

As from the start, their outrage was drawn from somewhere deeper than the immediate, spiralling events. Not every online threat results in actual violence but some do, and those that don’t leave their own mark.

Talking to Olivia’s friends you get the impression the battle for them is as much about dignity as security.

“This is something I have seen every single one of my friends go through and I’ve personally gone through it more times than I can count,” says Sophy, referring to the threat of online harassment more generally. “Basically, since I was 13 and the internet happened, it’s been happening.”

After a short wait the two young women are seen by a female officer who they greet with a USB stick full of heinous screenshots.

Under Australian law there are a number of options when attempting to prosecute online harassment, the most direct of which are found in Federal laws relating to the use of a “carriage service”. They make it illegal to “menace, harass or cause offence”, a bar surely cleared by the rape and death threats Paloma had endured.

Yet both young women would leave the police station with a sense of disappointment.

“I feel like the interaction could have gone a little bit further,” says Sophy.

“It didn’t seem like [the officer]didn’t want to help, but it did seem like there wasn’t anything specifically in place at that point to say ‘this is what you can do’.

“She kind of just took our details and gave us a reference number and said ‘I’ll be in contact in the next few days’. It would have been nice, I guess, to have some kind of confirmation of our options.”

They waited for further instruction from the police. By the end of the week – and at the time of writing – it still hadn’t come.

It was only when others started to intervene that Paloma and Sophy realised there were real avenues of legal recourse open to them.

Dr Emma Jane says of the women she has interviewed during her research only a small number took their problems to police. Most of them were “fobbed off”.

“It’s widely acknowledged that the police are not doing enough to support the female targets of this abuse. The platform managers [i.e. Facebook, Tinder, etc] themselves are not doing enough to tackle this abuse.

“The standard response women receive when they go to police is ‘take a break from the internet’. That is not possible anymore. Most people rely on the internet to do their work. Then there are all the social and personal dimensions to being online.”

According to Dr Jane there are parallels between the responses to women facing domestic violence and rape in the 1970s and women facing “cyber-hate” in the present – both are told they are part of the problem.

“My interviewees have said that the police say things like ‘take a break from the internet’, ‘change your profile picture, it’s too good looking’, ‘don’t be so provocative online’. It’s victim blaming.”

Their interaction with the police only pushed Olivia, Paloma, Sophy, and the group of young women who coalesced around the incident to ask further questions, spurred further by contact from a senior legal figure who encouraged them not to let it go.

All of a sudden they had started a campaign. It struck a chord, quickly drawing support.

Pushing on they tried to take the matter higher.

And that’s how their story, of hip-hop lyrics recycled and social media abuse, came to the attention of Greens Senator Larissa Waters.

The Queensland MP and member of the Federal Parliament is concerned the tale is not unique. She’s started to investigate, writing to the Queensland Police Commissioner to ask what kind of training police are getting, and whether it needs to be bolstered.

“We’ve spoken to a few of the rape crisis centres around Brisbane, where I’m from, and just gotten a bit of anecdotal evidence about what they think about the situation. They tend to agree that the laws are there but their experience is that police don’t take online threats as seriously as threats in real life,” she says.

Gregor Urbas, an expert in cybercrime at the University of Canberra, agrees and says a number of states and territories have updated their legislation to ensure offences like stalking remain practical in the digital age.

“It’s fair to say there is a sufficient legislative basis to find some kind of charge to prosecute most situations,” he says.

Here we have to take a brief timeout to quickly reflect on perhaps the most bizarre coincidence of this story, which brings us back to our old friend and latter day poet Aubrey Drake Graham (aka Drake).

In the late 90s a man named Brian Andrew Sutcliffe was charged with stalking Canadian television star Sara Ballingall, allegedly sending her threatening messages via email. The case forced the Victorian Parliament to pass new legislation ensuring the state had the power to prosecute such interactions, and Urbas points to it as a ‘leading case’ in the area.

Sara Ballingall was famous thanks to her role in the popular school-aged soap Degrassi High, a later incarnation of which would eventually launch the career of none other than a young Aubrey Drake Graham.

Urbas, who hasn’t heard of Drake, suggests that mirroring existing Federal laws at the state level, as has happened with hacking offences, could help clarify confusion about jurisdiction. He also suggests making sure police are “alive” to the movement of harassment and stalking in the digital world.

In a statement to New Matilda a spokesperson for the Australian Federal Police acknowledged that cyber bullying and online threats could be devastating for victims, and said the appropriate place to report matters was local police.

“Where inappropriate or illegal content is posted on social media sites, individuals can request operators of those web or social media sites to have the content removed/deleted. Cybercrime can also be reported via ACORN (Australian Cybercrime Online Reporting Network).” www.acorn.gov.au.

Meanwhile, Senator Waters is getting serious.

The Greens MP says she is planning on asking party leader Richard Di Natale to raise these matters with Prime Minister Tony Abbott at their next meeting, and may write to the PM asking him to bring it up with state leaders at COAG.

Back in Sydney, it’s a Thursday night, and a group of eight young women are sitting on the verandah of an inner city pub, MacBooks on the table, schooners and glasses of red in between. They’re talking about what comes next, and sorting out the wording of a petition about police responses to online harassment.

“We do live in a digital world and that’s what we’re focusing on, changing it for the future,” Paloma says.

Every now and again, as they trade tactics and jokes, an older man will veer onto the precipice of their conversation, bemused by the presence of the young women together, keen to interact. They’re met with polite but terse conversation, and inevitably keel off elsewhere in the bar.

Paloma says the threats of violence didn’t leave her afraid, except for one moment while travelling to work.

“The other night I was going to work, I work in a suburb which is quite obvious on my Facebook page and anyone can find that out. I started late at night and as I was walking up the street, it was the first time I started to look around and worry ‘who has seen my face’? Who had seen me on the Internet? Is this person around?

“They had photos of me, I’m completely by myself walking up Oxford Street at nine o’clock at night and it just sort of hit me, that was the only time I got very scared for my safety.”

On the pub verandah there’s music playing, mostly of an indie variety. At no point in the night does Aubrey Drake Graham get a look in.

Sophy, who had shamed Chris Hall from her own Facebook page before deleting the post, admits she feels some sympathy for him.

“In the end I don’t know who he is as a person and what he’s done previously, but this is one big mistake that we did catch onto, and we did take offence to, but from what his friends have said apparently he’s quite a nice guy.

“But at the same time I just feel like you should be kind of willing to deal with any repercussions that come from that.”

On the other side of the young women’s laptops the social media accounts of Chris Hall and Zane Alchin have gone dark. For now, it appears, they’ve been deleted, shrinking both men back from one corner of the digital world.

New Matilda contacted NSW Police for comment but it was not available at the time of publication.

* ED’S NOTE: New Matilda is attempting to locate Zane Alchin. Anyone who can assist can email Max Chalmers here.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.