There’s no emptier word in contemporary politics than “reform”. The word is used so often and so loosely that it scarcely means anything at all.

There isn’t a problem in the Commonwealth that can’t be fixed with a bit of judicious reform. If the problem is serious enough, you can call it a “brave” reform. For the very courageous, there are even “ambitious” reforms.

Greg Jericho has the canonical take-down of the “reform” chimera. “Reform,” he argued last year, is simply a policy someone agrees with. Want lower taxes? The answer is tax reform. Want to pay workers less on Sundays? Industrial relations reform! The economy is sluggish? That can be addressed by – you guessed it – economic reform.

And so everyone could agree on the value of this week’s National Reform Summit. According to the breathless spiel of its spruikers, “the National Reform Summit – sponsored by The Australian, The Australian Financial Review and KPMG — sought to build a consensus for reform and break the political deadlock that has increasingly frustrated policy change”.

Who are the people organising and attending the National Reform Summit? They are, quite specifically, Australia’s political class. Politicians, big media companies, industry lobby groups, think tanks, welfare bodies, trade unions and even the occasional academic all have a particular barrow to push. Written on the side of their handcarts is that wonderful word, “reform”.

Reforms are much loved by business groups and those representing special interests. Funnily enough, the reforms they tend to suggest seem rather similar to the policies that would best advantage their particular lobby.

When it suits, the left likes to jump on the reform bandwagon too. The National Disability Insurance Scheme, for instance, was championed as a visionary reform. Giving gay couples the right to marry is sometimes called “marriage reform”. The genius of reform is that, depending on the reform we’re talking about, everyone can be behind some version of it.

For instance, the Business Council of Australia attended the summit. What did the BCA recommend we should adopt as reform? More economic growth, basically. “The task at hand essentially comes down to growth,” the BCA’s Jennifer Westacott said at the close of the summit. “We commit to working with others to design and publicly explain a tax package,” she added. “We will model it so people are clear about the trade-offs.”

You can bet what that tax package will recommend: lower taxes for businesses and corporations, offset by higher taxes on consumption.

Peak welfare group ACOSS also had an agenda going into the Reform Summit. It was a lot less self-serving than the business lobby. The Social Services Council’s Cassandra Goldie argued that “policy solutions should be more creative.”

Tax loopholes should be closed, stamp duty should be replaced with land tax, and governments should get more efficient in the way they deliver services. More investment is required for disability services, for the unemployed, and for preventative and mental health. These moderate, centrist views are about as radical or revolutionary as the reform push gets.

Speaking loftily from the highest pulpit were the arch-bishops of the reform church, the economists. These special keepers of the reform flame know that only through constant and ongoing reform will Australia’s economy stay rich, prosperous, and productive. Productivity is their lodestar, and “productivity reform” their catch-call injunction.

And so we had former Treasury Secretary Martin Parkinson warning that standards of living will fall over the next decade if we don’t get our act together. “We’re sleepwalking into a real mess,” Parkinson proclaimed. Parkinson offered at least one concrete measure that he claimed would boost growth: removing the absurdly generous tax concessions for superannuation.

In its florid form, the reform cult takes its cue from the supposedly halcyon days of the Hawke-Keating governments, when the Labor Party embarked on an ambitious program of macro- and micro-economic reform. There were indeed significant changes: the dollar was floated, banking was deregulated, industrial relations laws were loosened, tariffs were torn down.

Plenty of policies we generally blame on that watchword “neoliberalism” were ushered in under the aegis of “reform”.

Keating and Costello freed up the Australian economy, giving it more flexibility and openness. Privatisation and deregulation continued; the Reserve Bank was made independent. They raised taxes on consumption and lowered taxes on capital. Under both Labor and the Coalition, union power declined, while corporate power increased. In a bipartisan fashion, the Hawke-Keating-Howard era also introduced policies like mandatory detention for refugees, mutual obligation for jobseekers, tuition fees for university study and a raft of onerous new anti-terror laws.

These reforms, we are told, set Australia up for the golden run of economic prosperity it has enjoyed ever since. Australia in 1980 was a rich but inward and inflexible economy; it is vastly more dynamic and open now. The reform era of the 1980s and 90s undoubtedly contributed to the growth and prosperity of the 2000s.

But the reform era also left many of the vulnerable in our society behind.

For many ordinary voters, the Hawke-Keating years were pretty tough. Lower tariff barriers saw wholesale deindustrialisation in sectors like manufacturing and textiles, clothing and footwear. The go-go years of the 80s gave way to sky-high interest rates, followed by a bitter recession in the early 1990s. The economy was only slowly recovering by the time Keating lost government.

When John Howard campaigned for office in 1995, one of his most effective lines was that Australia had enjoyed only “five minutes of economic sunshine.”

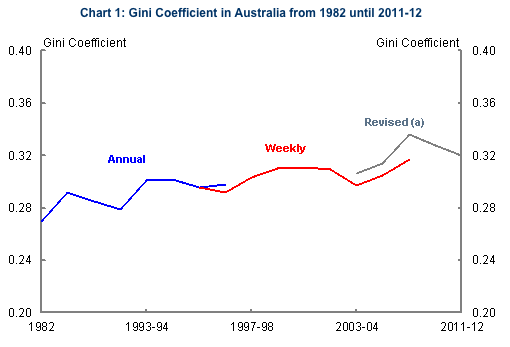

Inequality has steadily increased since 1982, as the chart above shows.

In real estate, in particular, and in capital accumulation in general, those at the top have streaked ahead of the middle classes. At the bottom 100,000 Australians are homeless on any given night, and perhaps a million of us are living in what one recent study called “chronic or persistent poverty or deprivation”.

Australia’s record on Indigenous disadvantage, on gender discrimination and on a dignified life with those with disabilities also leaves an indelible stain on our supposedly rosy achievements.

There seems to have been little effort at the Reform Summit to address endemic issues like poverty, inequality and disability. The idea that growth, or productivity growth, or innovation, will somehow solve all our problems still seemed to be the main solution to all our ills.

In truth, the fixation on growth shows the poverty of elite thinking. As heterodox economist John Quiggin argued in a lecture in May, the real reason that the political classes are so worried about “reform fatigue” is that the neoliberal reform program of the 1980s is now exhausted.

And, sure enough, we didn’t hear many new ideas at the Reform Summit.

Improving productivity growth is certainly a good idea. But it’s not a new one. And it’s a difficult one to pull off. A real attempt at productivity growth will require a sustained and long-term effort at raising educational standards, fostering innovation, and investing in research and development.

This won’t come cheap. It will require significant commitments to higher public spending in universities, in science and technology, in vocational education, in secondary schooling, and in support for start-ups and venture capitalists. Needless to say, Australia under Abbott is going backwards in all these metrics.

Much of Australia’s disappointing performance in business innovation rests with failures in management, particularly among the upper crust of old, white and male business leaders we pretend are somehow champions of reform. It’s an irony noted by more than a few observes that the Reform Summit was sponsored by two old media companies, News and Fairfax, that have proved manifestly incapable of innovating their way around the business challenges of the internet.

And then there’s the elephant in the room, climate change. There surely could be no greater reform challenge for coming decades than the decarbonisation of Australia’s filthy economy. And yet many of those at the Reform Summit were the same people who campaigned so strenuously against the Rudd-Gillard governments’ efforts to introduce a carbon price and cap on carbon pollution.

If the business community and News Corporation had lobbied strongly for a carbon price, instead of fear-mongering against it, there is little doubt Australia would still have one.

Tellingly, climate change was completely left off the Reform Summit’s agenda.

A good place to start “reform” might be to put a lock on that door from the outside

— Possum (@Pollytics) August 26, 2015

In other words, you could argue that the real problem with reform is the people advocating it. As commentator and poll blogger Scott Steel tweeted yesterday, “half that room is filled with people that got nearly every single thing about politics and economics, globally and domestic(ally), wrong for a decade.” The best prospect for reform, he pointed out, might just be “to put a lock on that door from the outside”.

I have a proposal. Let’s hear no more of this empty word, reform. Let’s try for some new words in our national conversation, like happiness, or equality, or justice.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.