Activists and environmentalists take note. In this special essay, Dr Lissa Johnson explains how to make people give a damn.

The Federal Court decision to set aside environmental approval for Adani’s Charmichael mega-mine has been hailed as ‘a great example of democracy in action’. Which it is.Our Government, however, is not happy about active democracy in this case.

Attorney-General George Brandis is “appalled” by a law that allows “anyone” (citizens), to bring an action against “massive developments” (squillionaires), on environmental grounds. Tony Abbott and Greg Hunt, apparently, are similarly unimpressed.

So affronted is Brandis that he hopes to “get rid of” the provisions in the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Act that enabled the action against Adani in the first place.

If only the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) deal were here. Adani might have been able to sue Australia through Investor State Dispute Settlement channels, potentially at taxpayers’ expense.

While the Federal Court decision is heartening, one can’t help but wonder about the fate of similar decisions under the TPP, currently being negotiated by our leaders. Details of exactly how far sovereignty, rule of law, and environmental and consumer protections stand to be corrupted by the agreement is, of course, secret.

As the window for finalisng the TPP narrows, thousands turned out across New Zealand over the weekend in protest. The US Government warned its citizens not to attend the demonstrations.

Even without specific details of the TPP, at a time when the world is setting critical emissions reduction targets ahead of the Paris climate talks later this year, placing transnational corporations above local law, potentially environmental law, makes no sense.

Watching these developments unfold, among other erosions of rights and protections, is like watching the cracked varnish of cosmetic democracy come peeling off, flake by flake.

In Australia we have had the unabashed election lies of 2013. Then the attacks on freedom of expression, liberty and privacy in the name of national security and borders. Then the cowing of the ABC so brazen that it prompted managing director Mark Scott to remind everyone that the ABC is a public broadcaster not a state broadcaster, in Australia not North Korea.

These devolutions, of course, have not come out of the blue. Since the 1980s academics and commentators have been warning of the democratic dangers posed by concentrated media ownership, John Pilger among them.

Going back a little further in democracy’s history, in 1787 the ‘father of the US Constitution’ James Madison proposed that the Constitution should “protect the minority of the opulent against the majority”. This, according to Noam Chomsky, was because “The determination was made that America could not allow functioning democracy, since people would use their political power to attack the wealth of the minority of the opulent.”

Perhaps Adani and the Government are feeling thusly attacked.

We needn’t take Chomsky’s word on the matter, however. Whether or not the US is a ‘functioning democracy’ was recently posed as an empirical question and put to empirical test.

In a 2014 paper, professors of politics and political science at Princeton and Northwestern Universities, Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page, tested the dominant competing claims about the nature of the US political system against each other.

They grouped literatures on the subject into four theoretical traditions, based on who in society is posited to most crucially influence government policy. Those four traditions are Majoritarian Electoral Democracy (democracy as we know it – by and for the people), Economic-Elite Domination (by and for affluent elites), Majoritarian Pluralism (by and for mass-based interest groups) and Biased Pluralism (by and for business interest groups).

To analyse the impact of each of these groups, Gilens and Page examined a national survey of public preferences regarding 1,779 proposed policy changes between 1981 and 2002. They also mined public records for actual policy outcomes on each of the 1,779 issues, along with preferences of interest groups for each issue.

As data-gathering efforts go, theirs was herculean. The authors note that there was “nothing easy” about it, requiring a “small army of research assistants”. It was also the first undertaking of its kind.

To test the theories against each other, Gillens and Page compared preference-outcome correspondence across the four theoretical traditions.

They found that “economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on US government policy, while mass-based interest groups and average citizens have little or no independent influence”.

Little or no independent influence. That’s not much.

In fact, Gilens and Page described the influence of average citizens’ preferences as “minuscule, near zero”.

They concluded that “pure theories of Majoritarian Electoral Democracy can be decisively rejected”. What the US seem to have, they propose, is “democracy by coincidence” in which “ordinary citizens get what they want from government only when they happen to agree with elites or interest groups that are really calling the shots”.

It seems founding father Madison got his wish.

And no wonder our ministers would like to dismantle the act that enabled a win for average citizens against government and an economic elite. That’s not how things are supposed to work.

Despite the seminal nature of the Gilens and Page study and its implications for Australia, Googling “Gilens and Page” in Australia yields only one news result, a piece in the Monthly in June last year. Plus a couple of articles on other topics, with a mention of Gilens and Page in readers’ comments.

But even if the study had been reported more widely, would most Australians have even cared? A Lowy Institute poll released around the same time, found that only 60% of Australians, and less than half of those aged 18-29, considered democracy preferable to other forms of government.

Such apathy towards democracy is just as well for the Abbott Government. Spruiking coal on behalf of mining interests in the face of an urgent climate crisis, and against economic reason, would be trickier if everyone took “by and for the people” seriously.

As would turning a blind eye to the money trail between big coal and government policy, such as industry funding of climate denial and policy-shaping advertising blitzes, the revolving doors between government and industry or the large political donations to the Coalition from mining and energy interests.

While there is no evidence that political donors “buy” politicians, recent US research has demonstrated a link between campaign funding from business interests and greater political responsivity to wealthy constituents at the expense of majoritarian policies.

Granted, the Australian system does represent the interests of the majority better than the US, particularly with respect to health and education. If the Abbott Government had its way, however, this would soon be a thing of the past. Christopher Pyne, for instance, has higher education in his sights again.

What majoritarian foothold the ‘average citizen’ has in Australia is currently on the rocks. If ever there was a time for Australians to worry about majoritarian erosion it is now, particularly given our Government’s majoritarian nihilism with respect to climate change.

Even the demonstrably Elite-Dominationist US has committed to emission reduction targets aimed at keeping global warming below catastrophic levels ahead of the Paris climate talks. The Australian Government’s targets, in contrast, keep us on track towards climate catastrophe.

The UK Government’s climate advisor has called Australia’s targets “pathetic” and Richard Denniss of the Australia Institute warns that if Australia succeeds in its coal export ambitions, “the world will fail in its efforts to tackle global warming”.

Of all majoritarian concerns, protecting the human habitat is surely the most fundamental. Of all minoritarian projects, destroying it on behalf of mining elites is surely among the most sinister.

SO WHAT kind of system is this? And who even cares? Although Gillens and Page have been cited as dubbing the US a Plutocratic Oligarchy, the authors never drew that conclusion. They left the issue open, beyond saying that “America’s claims to being a democratic society are seriously threatened”.

As it turns out, defining the political and economic nature of US society has created room for some unusual ideological bedfellows.

Economics professor and former economic advisor to Jeb Bush, Randall G Holcombe, has advanced a hypothesis on the subject, writing in the journal of the libertarian think-tank The Cato Institute earlier this year.

The Cato Institute has promoted climate science denial and was originally called the Charles Koch foundation, after its founder Charles Koch of Koch Industries, the second largest privately owned company in the US, with coal, oil and gas interests, among others.

Koch industries was named in a Stanford University Study as a major financier of climate change denial and other climate change countermovement efforts.

In his Cato Journal article Holcombe makes the case that the US, typically considered a democratic capitalist system, is actually a ‘political capitalist’ system. This, he explains, is “a system in which the political and economic elite design the rules so that they can use the political system to maintain their elite positions” and “in which business controls government more than government controls business.”

The TPP comes to mind. As does Brandis’ wish to ‘get rid of’ inconvenient provisions in environmental protection acts in the interests of companies like Adani.

Holcombe notes, “This system of private ownership but government management of the economy falls under the heading of fascism…. Political capitalism is closer to fascism than to either capitalism or socialism”.

On this point Holcombe and John Pilger might agree. Pilger has also written on the rise of fascism in the West.

Noam Chomsky, one of the most cited individuals in the world, makes similar arguments, calling Western business elites “huge private tyrannies… which are about as totalitarian in character as any institutions that humans have so far concocted”.

‘Fascism’ says Pilger. ‘Totalitarianism’ says Chomsky. ‘Agreed’ says Randall G. Holcombe, former Republican advisor. To Jeb Bush no less.

Terminology aside, the ‘average citizen’s’ complacency over whatever-this-system-is is all the more striking given how badly our Undemocratic/Political Capitalist/Elite Dominationist/Biased Pluralist/Crony Capitalist/Protofascist/ Outright Fascist/Bankster/Rentier/Oligarchic/Plutocratic/Kleptocratic/Murdochratic system is performing.

Global wealth and income are ever more unequal and polarised, entire European countries are in economic free-fall, the Middle East is in tatters thanks to policies that serve the Western military industrial complex, millions of innocent civilians are dead or displaced, and humanity is marching towards climatic disaster with the possibility of human extinction.

Quite a scorecard.

And still, 48 per cent of Australians would re-elect the elitist coal-fuelled Coalition on a two party preferred basis, given the chance. Not a majority, but nevertheless quite a lot. Millions in fact.

This despite the latest Lowy Poll results showing that 63 per cent of Australians would like the Government to set a good example by adopting significant emission reduction targets ahead of the Paris climate talks. The Government even gets a failing grade for it’s handling of climate change (4/10).

Economic optimism is also 23 per cent lower than it was at the nadir of the GFC, the largest fall since 2005.

Even so, 48 per cent of people would still vote the Government back in.

Granted, a sizable proportion of that 48 per cent probably consumes Murdoch media, but that is a two-way street. Those people seek Murdoch publications out.

And even a Murdoch audience knows about climate change.

Al Gore started singing it from the mountain tops in 2006. His film won two Academy Awards and was the 10th highest grossing US documentary at the time.

The Pope is shouting about it. The UN is shouting about it. Everyone knows about it.

Most Australians even realise that our Government is backing the wrong horse, with only 17 per cent believing that coal should be Australia’s primary power source in 10 years, and 69 per cent nominating renewable energy. People aren’t buying the Government’s three cheers for coal.

According to the latest Climate Institute survey 63 per cent also believe that the Abbott Government should take climate change more seriously and 59 per cent are “greatly concerned” that the Government underestimates the seriousness of the matter.

Yet still almost half of the population would have the Government back for more.

With the doomsday clock showing 3 to midnight, having been moved forward early this year on account of climate change and the nuclear arms race, its custodians citing “failures of leadership” that “endanger every person on earth”, you would think that more people would be more careful about who they elect.

The fact that they aren’t suggests powerful psychological forces at work. Powerful enough to withstand the opinion of 97 per cent of the world’s scientists. And the Pope. And the UN And the prospect of global catastrophe.

What could those psychological forces be? And how can they be overcome?

IN 1994 psychologist John Jost of New York University (NYU) and his colleague Mahzarin Banaji of Yale and Harvard proposed a novel concept to explain this kind of conundrum. Why do people support social and political arrangements even in the face of good reasons not to, and even when they themselves stand to suffer as a result?

The answer, they suggested, is a human tendency towards what they called ‘system justification’. Just as individuals are driven to view themselves and their social groups in a favourable light, Jost and Banaji argued that people are also driven to view the wider systems on which they depend in a favourable light.

As it turns out, Jost and Banaji were right. Many years of fruitful research later and a 2011 review article notes, “By now hundreds of studies have supported predictions derived from system justification theory, vividly illustrating the ways in which people uphold the status quo and minimize or overlook its flaws, thereby perceiving it as more legitimate than it actually is.” Specifically, more stable, beneficial, good and just.

Believing in the existing social, economic and political order helps people to feel safe and secure (existential needs), that life holds coherence and meaning (epistemic needs), and connected to others through a sense of shared reality (relational needs).

System justification research has proven most noteworthy for its ability to explain counterintuitive phenomena that existing self- and group-based frameworks could not.

For instance, while members of advantaged, high status social groups support the status quo for obvious, self-enhancing reasons, members of disadvantaged groups often do the same, rationalizing their own disadvantage and showing paradoxical biases against themselves and their own group. Or, as Jost says, becoming “complicit in their own subordination”.

On closer examination, this auto-oppressive impulse is mediated by a person’s experience of powerlessness and dependence.

In one series of studies, powerlessness of various sorts, whether experimentally induced or measured by questionnaire, was associated with greater legitimation of racially unequal incarceration rates, the wealth gap, the gender wage gap, and government authority in general.

In another set of studies, being bamboozled by complex terminology on sociopolitical issues (the environment, energy and the economy) led to increased feelings of dependence on government. This dependence in turn fostered trust in the government, avoidance of information on the issues in question, and greater faith that the government knew what it was doing, including trusting government officials over scientists to solve energy-related problems.

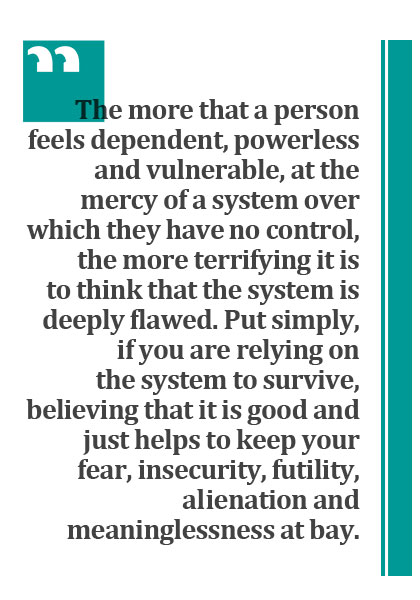

With psychological needs in mind, a system’s greatest victims being its greatest supporters makes sense. The more that a person feels dependent, powerless and vulnerable, at the mercy of a system over which they have no control, the more terrifying it is to think that the system is deeply flawed.

Put simply, if you are relying on the system to survive, believing that it is good and just helps to keep your fear, insecurity, futility, alienation and meaninglessness at bay.

Another counterintuitive implication of system justification is that the more flawed a system, the more motivated people become to support and defend it. Cracks in the system (system threat) jeopardise the psychological sense of safety, meaning and connection.

One of the most common sources of system threat is criticism. In countless studies, when people read passages or articles highlighting flaws in their political, economic or social arrangements (eg. “Many citizens feel that the country has reached a low point”), they respond defensively, with greater rationalisation of, faith and trust in, and support for the system in question.

Given that it functions to protect people from harsh realities, John Jost has described system justification as a “fundamental delusion” and a variety of “self-deception”, a common feature of human psychology.

Like other self-deceptions, the system justification impulse is considered “profound”, serving a “deep psychologically palliative function” by meeting existential, epistemic and relational needs.

Of course not everyone manages their existential, epistemic and relational needs in the same way. Accordingly, people differ in their tendencies to system-justify.

System justification correlates with political conservatism or right leaning political ideology and other inequality-justifying beliefs. It also correlates with self-deceptive tendencies in general (as does political conservatism).

People low on these qualities, such as the majority reading this article no doubt, are thought to be better able to manage their feelings of fear, uncertainty, meaninglessness and estrangement in society.

They are not driven to escape into self-deception. They can face the reality of their system’s flaws.

But what of those who can’t?

What does their psychological resistance to reality mean for those trying to communicate the urgency of pressing social issues such as climate change?

Communicators are in a bind. Presenting the reality of a serious social problem, a necessary and vital task, creates system threat. For those so inclined, system justification then kicks in, with all the resistance to reality and social change that that entails. The problem drags on, the alarm is sounded louder, system justification intensifies and so-on, in a mutually reinforcing, socially immobilising, loop.

Perhaps this is why the percentage of Australians who consider global warming to be a “serious and pressing problem” has fallen to 50 per cent in 2015, down from 68 per cent in 2006.

It might also explain why so many Australians are willing to participate in their own subordination by polluting elites, at the expense of every person on earth.

As if system-justifiers needed another reason to put their heads in the sand, an additional factor driving system justification is an issue’s urgency.

It is probably no surprise, then, that climate change packs a system-justifying punch.

IN A doctoral thesis and journal article on the subject, Irina Feygina of NYU found that system-justifying beliefs predicted denial of environmental realities and resistance to pro-environmental action across a range of methods and measures.

Previous research has also linked various system justifying ideologies and attitudes to climate change denial and environmental inaction.

Feygina says, “This evidence may well constitute the most dramatic demonstration to date of the social costs associated with system justification, insofar as people seem willing to sacrifice not only their own long-term self-interest, but also the well-being of others and perhaps even the planet as a whole”.

As she points out, climate change carries powerful system threats on many levels, “not only because of the scope and unpredictability of the projected disasters” but also because it requires re-thinking “ideas on which much of modern Western civilization is predicated”, such as consumerism, materialism, the free market and the primacy of industry, as well as “highlighting the failures of political leaders”.

Throw in confusion, powerlessness, dependence and urgency, and system defences go right up.

In Australia we have the added element of our Prime Minister’s incessant ode to coal, rubbing our noses in the grimy reality of our domination by economic elites, and the fact that we are an international embarrassment.

Little wonder more Australians would rather focus their fear and concern on ISIS/Daesh (69 per cent) than climate change (37 per cent). No need to stomach ugly home truths there.

What does this mean for humanity’s ability to turn things around in time to keep global warming within 2 degrees Celsius? Or less?

Fortunately, research has begun investigating ways to overcome system-justifying barriers to change. Findings are in their early days, but they are illuminating, and given the urgency of climate change it seems prudent to make use of what we’ve got.

In the second half of her thesis, Feygina examined whether certain kinds of climate messages might channel system justification in a pro-environmental direction.

She found that framing environmental action as “system sanctioned”, by deeming it patriotic and American, did just that. After reading a passage describing the seriousness and urgency of climate change, participants also read the statement, “Being pro-environmental allows us to protect and preserve the American way of life. It is patriotic to conserve the country’s natural resources.”

These two sentences eliminated the anti-environmental effect of system justification.

To reach a system-justifying audience, Feygina recommended “creating the perception that caring about one’s country (and its socioeconomic institutions) is compatible with a concern for the natural world” rather than pitting the environment and the socioeconomic order against each other, which she described as “deeply flawed”, psychologically speaking.

She proposed that, “Under such circumstances it is conceivable that many more citizens (including more of those who are presently sceptical) will embrace and begin to justify a new, more environmentally sound regime”.

Among her other recommendations were emphasising themes of competence, possibility and capability, given that a sense of efficacy is required to overcome the immobilising effects of fear.

Referencing wider systems that are inclusive and global, rather than national, may hold additional promise, particularly in Australia where the global status quo is more pro-environmental than it is at home. This might also avoid unwelcome side-effects, given that appealing to national identification, particularly in a context of fear, can stir destructive intergroup processes such as prejudice and intergroup violence.

Messages to system justifying Australians, then, at an evidence-based guess, might frame climate mitigation as part of familiar capitalist endeavours, and as compatible with ‘tradition’ ‘social institutions’ ‘custom’ or ‘established practice’.

Such capitalist traditions might, for example, include being competitive, forward-looking, a peer in the global economy, technologically and industrially relevant, commercially innovative and adaptable, economically secure (vs vulnerable to global coal demand), committed to jobs, employment and emerging markets, equipped to continue consuming and producing with green energy (vs inhibited by dirty energy), and so-on.

In short, channelling existing socio-economic norms in a pro-environmental direction.

Or, to borrow from ‘Carbon Nation: a climate change solutions movie that doesn’t even care if you believe in climate change’, “if you don’t give a damn about the environment, do it because you’re a greedy bastard and you just want cheap power”.

While frank communication has proved effective for a substantial proportion of the population, and remains imperative, in order for climate mitigation to succeed a larger majority must also be reached.

Given that majoritarianism only works when ‘the people’ are accurately informed, communicating creatively around, over, under and through system-justifying blind spots is likely to prove crucial in combating anti-majoritarian climate destruction and advancing climate change adaptation.

Irina Feygina notes, “Given what we have learned, it seems unlikely that direct and widespread confrontation of environmental problems will occur unless psychological attachments to the status quo are addressed, and their detrimental impacts alleviated”.

Those who struggle to face stark social realities need the comforter of a trusted and familiar system to help them cope. Cloaking climate mitigation in that very comforter may help those people to open their eyes. And be more careful about who they elect.

Fingers crossed.

* Dr Lissa Johnson is a columnist for New Matilda and a clinical psychologist. You can find out more about her work here.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.