This week the Federal Environment Minister took threatened species recovery a step in the right direction, unveiling a national strategy to turn back the extinction rate.

There are some really positive things in Greg Hunt’s plan, and the non-government sector is keen to engage with it productively.

It follows on from another initiative, the establishment of a Threatened Species Commissioner, which was welcomed by green groups last year.

But there is also a feeling that much of the plans’ benefits will be overshadowed by a far less laudable trajectory the environmental policy space has embarked on under the Abbott government.

The plan sets a range of ambitious goals – notably to get 40 species, 10 birds and 10 mammals, off the endangered list within 20 years – but it appears there’s little new funding to do it with.

Much of the plan is devoted to plugging the government’s existing policies, and the feeling amongst stakeholders is that the Commonwealth is largely shifting money around through its pet channels, like the Green Army, 20 Million Trees initiative, and National Landcare Programmes.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with that, and the environmental lobby have welcomed government promises for more targeted use of conservation dollars, but a recent Australian Conservation Fund report highlighted the scope of the problem when it found an annual $200 million injection was needed to boost recovery efforts.

Announcing the plan, Hunt said: “We can't win the war on extinction by doing more of the same, so the Threatened Species Strategy provides us with an ambitious plan to turn species’ trajectories around.”

Environmentalists agree, but argue that if Hunt wants to wage a ‘war on extinction’ there simply needs to be more funds. Hunt’s media release said the government had committed “$6.6 million to threatened species projects to kick-start the plan”.

It’s a far-cry from $200 million.

And Hunt’s plan is, as he said, “ambitious”: “By 2020, I am setting hard targets for real improvements to 20 mammals and 20 birds on our national threatened species list as well as for 30 priority plant species,” he said.

But Glen Klatovsky, Director of Places You Love, an alliance of 40 of Australia’s most active environmental groups still has concerns.

“The Plan fails to provide adequate money for the ambitious goals and it is not clear whether this is new money,” Klatovsky said.

The plan is loaded with platitudes about partnering with state governments, NGOs, Indigenous Rangers, and community groups, but it also carries high expectations of their financial contributions.

“It does call a lot on, and ask a lot of, state and territory governments, environmental groups, philanthropists, and other partners and I don’t necessarily have a problem with that because not one agency or group can solve this problem,” said Darren Grover, World Wildlife Australia’s Threatened Species expert.

“If there was a huge big bucket of money that goes with it, it’d be perfect,” he said.

“There’s not the resources there to support it, though. All these other issues seem to be business as usual or even business in hyperdrive, while we still try and save these species.

“We want to be a key contributor to the implementation of this plan but the Commonwealth still has to do the heavy lifting in terms of providing the funds.

“We just don’t have the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars to make this plan come to fruition.”

Ironically, the government’s move to engage environmental groups as funding partners in the battle against species extinction comes at the same time the government is pursuing an inquiry into their tax break on donations, which threatens large proportions of their funding.

Last week, committee member and government MP George Christensen pre-empted the outcome of the government inquiry when he warned NGOs it is “time to get the donations in” before the committee reported.

“I think everyone got caught up in the euphoria of a big bold plan and excited about the idea of moving forward on these issues,” Grover said.

“But lurking in the background were things like the fact there’s still [a]devolution of environmental powers back to the states and the approvals of coal mines and other large scale developments that are taking away hundreds, if not thousands, of hectares of habitat.”

The Wilderness Society agrees, and said “if minister Hunt is serious about saving forest-dependent threatened species, he must act now to stop logging in their forest habitat”.

The organisation’s Victorian Campaigns Manager, Amelia Young, said iconic Australian species like the Leadbeater's Possum and the Swift Parrot, found nowhere else on Earth, are at risk of extinction because of ongoing logging.

The Leadbeater Possum was listed by Hunt for “emergency intervention”, but the Wilderness Society said the best intervention he could mount was to use his powers to stop the logging of its Mountain Ash habitat, which is also critically endangered.

Klatovsky agreed that habitat clearing remained a problem, and reiterated the concerns of Places You Love and environmental law experts over a government plan to devolve the Commonwealth minister’s powers back to the states and territories.

“I think one key point is that we commissioned advice from the Australian Network of Environmental Defenders Offices about the adequacy of the state and territory governments’ laws to ensure that the environmental protections required under the [Federal omnibus law] are delivered, and that advice demonstrated that all state and territories failed to meet the standard,” he said.

The CEO of World Wildlife Fund Australia noted that “currently the federal government only has a role where projects impact our most important places and wildlife” and said this should continue because “these impacts transcend borders and cannot be handballed to the states and territories”.

This broader context is why, in the wake of the Melbourne Summit on Threatened Species, there was a distinct feeling amongst conservationists that while the government had addressed some important issues, it has not resiled from its pro-developer tendencies.

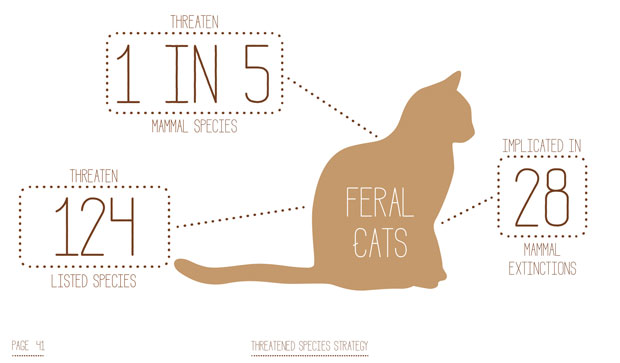

By way of example, Hunt said that by 2020 he wants to see two million feral cats, which are undoubtedly a major threat to Australian wildlife, culled. He also aims to secure “five new islands and 10 new mainland ‘safe havens' free of feral cats, and control measures applied across 10 million hectares”.

While he welcomed the move, Klatovsky said the “good things the government is investing in [come]at the expense of really dealing with some of the fundamental causes and with a belief that by diminishing environmental regulation and implementing cat eradication programs you’re going to end up with a better environment”.

Environmental lawyers warn the devolution of powers to the states will take conservation law back 30 years and make it easier for developers to get their projects approved – something that won’t be helped by culling cats.

It’s a cognitive dissonance which is somewhat emblemised by the near exclusion from the plan of action on climate change, the most overarching threat to a biodiverse future.

It’s true the fund is focused mostly on a five-year term, but Blair Palese, the CEO of climate advocacy group 350.org, said research to identify at risk species and plan for a climate-changed future needs to kick in at some point.

"With no plan for how to address climate change and blanket support for the dying fossil fuel industry, the Australian Government is actually encouraging more coal mines and gas projects that are one of the biggest threats to habitat destruction nationally,” she said.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.