The recent claims from former Queensland Labor MP Gary Johns that “a lot of poor women in this country, a large proportion of whom are Aboriginal, are used as cash cows” who are “kept pregnant and producing children for the cash” are somewhat alarming, but not surprising.

Female anthropologist Phyllis Kayberry noted back in the 1930s that Aboriginal women were viewed by white, male anthropologists as “no more than ‘domesticated cows’” (2004, 9).

The similarities here are by no means coincidental.

Aboriginal people have long been depicted as animalistic, not quite human, and accordingly were counted among the flora and fauna up until the 1960s. The depiction of Aboriginal women as cows more specifically suggests that we are not just animals, but that we are the most docile creature lacking agency over our own lives.

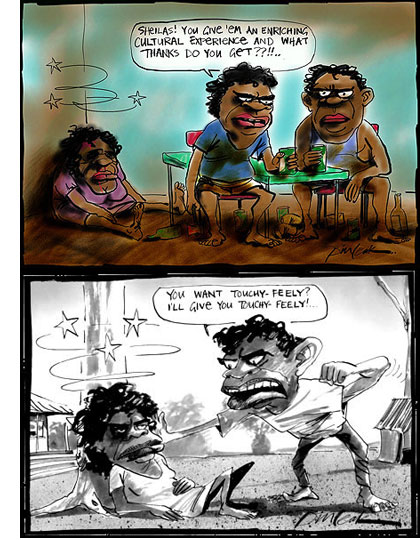

This docility is evidenced in a series of caricatures published in The Australian by cartoonist Bill Leaks a few years ago. The fact that an issue as serious as domestic violence can readily and repeatedly be made light of when the victims are Aboriginal women is further evidence of the ongoing dehumanization of Aboriginal women.

Prime Minster Abbott’s suggestion at the 2013 Garma Festival that Aboriginal women “were cowering in their houses or huts” again reveals to us the construction of Aboriginal women as both primitive and powerless.

These contemporary narrative possibilities are reproductions of colonial constructions of Aboriginal women which served to enable the ongoing exploitation of Aboriginal women for labour and sex by white men. They enabled the forced removal of children from their Aboriginal mothers and they enable the ongoing regulations imposed upon the lives of Aboriginal women in this country today, most notably evidenced through the Northern Territory Emergency Intervention, as well as Income and Alcohol Management Plans.

I agree that the abuse of Aboriginal women is real and it must stop. However it must be recognized that the deployment of Aboriginal women as passive, docile and incapable objects to justify the ongoing regulation and control over Aboriginal lives and lands also constitutes a form of abuse that, too, must stop.

I am an Aboriginal mother of five children, but I am not a cash cow. I live in one of the most socioeconomically disadvantaged communities in Brisbane, but my decision to have a large family is not a product of my “lack of education and lack of employment”. It is not indicative of my lack of control over my reproductive organs.

I am not a recipient of government support to provide for my children (i.e. Family Tax Benefit, Child Care Rebate etc) and I certainly don’t begrudge those who are. While my reality may contest the narrative truths of Aboriginal women as articulated by Johns, it does not prohibit me from experiencing the social stigma resulting from such representations.

I know that everyday there are presumptions made about my capabilities simply because I’m an Aboriginal woman, regardless of my professional achievements, my community involvement, my parenting practice and socioeconomic status.

Throughout much of my life, non-Indigenous observers have suggested to me that my achievements place me as an ‘example for’, or ‘exception to my people’.

Strangely enough, my life choices have not been made in spite of ‘my people’, but in fact have been inspired precisely by the agency, activism and achievements of ‘my people’ and more specifically Aboriginal women; women from within my family and community, women who have nurtured my development, women who are leading the way in their own professions, women who are driving community organizations and women who are driving change in their own families and communities.

And I guess this is what alarms me most about the narratives produced by white men about Aboriginal women… they simply don’t tell the story that I know as an Aboriginal woman about Aboriginal women.

Goenpul scholar Professor Moreton-Robinson (2001, 1) points out:

White Australia has come to "know" the "Indigenous woman" from the gaze of many, including the diaries of explorers, the photographs of philanthropists, the testimony of white state officials, the sexual bravado of white men and the ethnographies of anthropologists. In this textual landscape Indigenous women are the objects who lack agency. The landscape is disrupted by the emergence of the life writings of Indigenous women whose subjectivities and experiences of colonial processes are evident in their texts.

Sadly, in Australian public discourse, Aboriginal women remain subjugated by white men in this textual landscape.

If Johns is really concerned about the emancipation of Aboriginal women, then he must also recognize his complicity in undermining this task.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.