Since the United Nations was set up in 1945, 750 million people in 80 new countries have become free to rule themselves. Neither Aborigines nor Torres Strait Islanders count among them.

Scotland was given the right to decide in 2014 and Catalonians in Spain immediately sought the same right. The Spanish Constitutional Court immediately declared the proposed referendum illegal. In the meantime, not a squeak of a call from Aboriginals has been heard. All we want, it seems, is to be ‘recognised’.

From the early days of the National Aboriginal Consultative Committee (NACC) in 1974 through the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) in the 1990’s to the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples today, Aboriginal people have never had real power. Decisions are still made by white politicians and public servants.

We need to look ahead, beyond the next financial year. We need 20 to 30 year campaigns that we can all rally around. Different Aboriginal leaders call for different strategies. Some for constitutional recognition, some for more jobs and better education, while others for a $5 billion fund for Aboriginal investment. Others call for more land, representation, and protection of culture. Many have called for sovereignty, a treaty and self-determination.

Despite these differences, all leaders have one thing in common: they want a better deal for Aboriginal people. What models then might capture these various goals so that nearly all those suggestions are satisfied?

One model worth looking at is the 7th State: A defined territory in Australia made up of Aboriginal-owned or native title lands; an elected Assembly with powers of State governments; having its own constitution; all Aboriginal people having a right to participate (by voting or standing for elections to the Assembly) regardless of where they live, plus any non-Aboriginal residents within the territory; and established by Commonwealth legislation. That summarises a new 7th State of Australia.

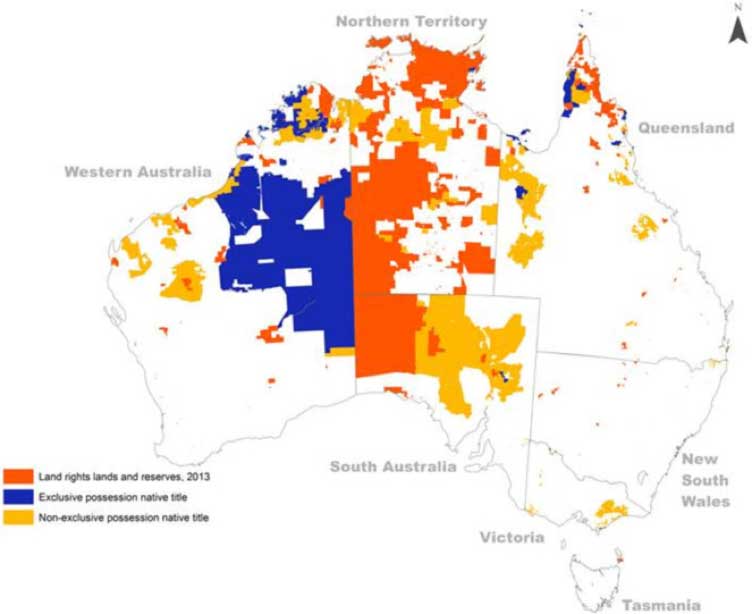

The map below shows the current Aboriginal legal interests in land.

What would an Aboriginal State be responsible for?

States have responsibility for their parliaments/Assembly, elections; for law and order (including customary law) police and prisons; for religion, education, health, housing, main roads, public transport, electricity generation and supply, agriculture, vacant lands, local government, state taxation, environment, and land use and planning.

The Aboriginal State would have these powers and be free to send delegations to various international forums (so long as it did not try to represent Australia, which it would not), have its own flag and anthem, and could even negotiate for full recognition of Aboriginal passports and an Aboriginal Olympic team.

Treaty

Another option is a treaty. The importance of indigenous sovereignty, as Larissa Behrendt suggests, is that it forms the foundation for a people’s rights and entitlements. Supremacy of authority over indigenous peoples and their lands resides with the peoples themselves.

A treaty is de facto acknowledgement of Aboriginal sovereignty, even if sovereignty is not mentioned in the treaty. It follows that if the purpose of a treaty is to provide a remedy for historic grievances and aspirations of Aboriginal people, and because what is written into a treaty delivers on Aboriginal expectations, the thorny issue of sovereignty should not destroy the possibility of a treaty.

Treaty enforcement

Suppose Pat Dodson, acting on behalf of Aboriginal people, and the Prime Minister on behalf of Australia, signed a treaty. The document itself would not create any rights nor impose any obligations. ‘Aboriginal people’ as such, have no legal personality and cannot sue as a people.

Until the treaty was legislated, the document would not be enforceable.

A politician’s promise does not create rights. The New Zealand Treaty of Waitangi has no independent legal status other than where statute law refers to and applies its provisions.

Legislation is needed to make a treaty legal and enforceable. Federal Parliament could legislate a treaty without the cost and complications of a referendum. The down side is that a legislated treaty could later be repealed by an unfavourable parliament. A treaty not cemented in the constitution or protected by international scrutiny is insecure.

Advantages of 7th State over a Treaty

• Both need to be legislated at the Commonwealth level to come to life. Neither requires constitutional referendum.

• A legislated treaty can be unlegislated. A 7th State cannot. The constitutional provision (s.121) that allows the Commonwealth the power to establish a new State, does not allow the Commonwealth to undo it – the Commonwealth Parliament only gets one shot at it. Thereafter, the State is protected by the constitution itself. But with a treaty, any Parliament that legislates a treaty can legislate to undo it.

• The entitlements under a 7th State – territory, legislative Assembly, economy raising powers – are probably the very features a treaty might seek anyway. A 7th State is a treaty in practice. It short-circuits the process by delivering, not promising.

If having responsibility over a third of the lands of Australia under a 7th State, run by an Aboriginal Assembly elected by Aboriginal people, with an Assembly protected from Federal interference by the constitution is not the right model, then what is?

* Michael Mansell is a Palawa man, a lifetime Aboriginal activist, and a lawyer.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.