Does Australia have a housing bubble?

The question, long a topic for debate among economists and policy wonks, has spread suddenly into the political mainstream this week, after comments from the Secretary of the Treasury John Fraser in Senate Estimates.

Fraser was asked whether property prices in Australia represented a bubble. “When you look at the housing price bubble evidence, it's unequivocally the case in Sydney,” the Treasury Secretary replied. “Unequivocally.”

They were strong words. Top economic policymakers are generally loathe to utter the B-word, lest it spark fear among investors and pop the very vesicle they are describing.

Notoriously, former US Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke nonchalantly dismissed concerns about the US housing bubble in the years before it popped. Despite the white-hot property market of 2005, the incoming Fed chairman stated at the time that house price growth “largely reflects strong economic fundamentals”.

In the event, falling US property prices destabilised the entire global economy, as subprime mortgage-backed securities linked to dodgy home loans took down US merchant bank Lehman Brothers. The resulting global financial crisis required government bail-outs of much of the world’s banking system; rich economies such as Britain and Spain are still recovering.

So when the senior public servant in Australia’s Treasury warns of a bubble in our largest city, you’d think the government would be concerned.

Not Prime Minister Tony Abbott. Asked about Mr Fraser’s comments in Question Time this week, the Prime Minister claimed that he wanted house prices to rise.

“As someone who, along with the bank, owns a house in Sydney, I do hope that our housing prices are increasing,” Prime Minister Abbott said. “I do want housing to be affordable, but nevertheless, I also want house prices to be modestly increasing.”

It was a perfect example of the blindness of Australia’s political class to the growing risks of a property bust. As the ABC’s Michael Janda – one of the savviest commentators on the slow crisis enveloping Australia’s property market – wrote on Tuesday, it was telling commentary on the failure of Australia’s policymakers to address dangerous imbalances in our economy.

“In that sentence, Mr Abbott summed up everything that's gone wrong with Australian housing policy over the past three decades,” Janda observed.

Australia’s economic policies are absurdly favourable to landlords and property investors. Negative gearing allows a taxpayer to gain a tax advantage for losing money on her investment. Capital gains tax does not apply to the family home. Land taxes are low. Tenants are treated as second-class citizens, with few of the rights accorded to European renters.

Most importantly, money is easy, with interest rates at record lows and banks showing few signs of caution when lending to property investors.

House prices in Australian capital cities have been growing for decades. There was strong price inflation throughout the 2000s, halted only temporarily by the global financial crisis after 2008.

But it has only been in the last 18 months or so, as the weakening economy has spurred the Reserve Bank to repeatedly slash interest rates, that a fully-fledged mania has taken hold, particularly in Sydney.

In the first quarter of 2015, Sydney house prices were growing five times faster than wages.

Stories abound of 3 metre-wide terraces selling for a million dollars, or of house auctions with bidding so strong they sold a million dollars above the expected price.

My favourite tale of Sydney’s housing mania was the recent sale of an unrenovated 30 square metre studio in Sydney’s Centennial Park for $366,000 – $91,000 above its asking price. The flat had no cooking facilities of any kind, and was described by the Sydney Morning Herald as “uninhabitable with its mould-covered bar fridge and rusty bath.”

Needless to say, it can’t go on like this. Housing prices in Sydney and Melbourne are now at irrational levels, and at some point the bubble must burst. Indeed, we may be seeing the beginning of that deflation this month, with the Corelogic index showing that house prices are down 1.4 per cent from their April-May peaks.

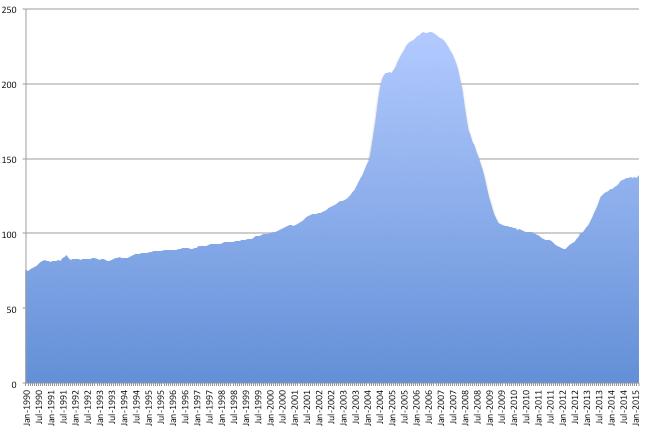

What happens when a housing bubble pops? This graph of house prices in the US city of Las Vegas illustrates the rollercoaster vividly.

Home prices in Las Vegas grew slowly until the mid-2000s, when they suddenly shot into the stratosphere. At the peak of the boom in late 2006, home prices were rising so swiftly that investors could flip properties for a handsome profit after holding them for just a few months.

When the crash came, prices corrected savagely. At the bottom of the trough in 2012, the Case Shiller index for Las Vegas was trading at 1996 levels. A full sixteen years of housing value had been wiped from the market.

It’s easy to see how deflation of this scale can damage an economy. As house prices fall, their owners are often forced to sell at a loss, or hold onto unproductive assets in the vain hope of one day making good on their investments. Confidence craters, and consumers stop spending. Banks and financial institutions leveraged to the inflating bubble also often collapse. A long and painful recession is the normal result.

Property busts can cripple economies for years afterwards. Japanese property prices in central Tokyo have still not returned to their 1980s levels; it took almost a century for Melbourne land prices to return to their levels of 1888.

So the potential risks for Australia are real, and very significant. Yet our Prime Minister remains blissfully unconcerned.

Meanwhile our Treasurer is talking up recent GDP figures as though they are evidence of a renewed boom, when they are nothing of the sort.

Economic growth figures released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics yesterday show that Australia’s economy remains in the doldrums. While quarterly growth was a relatively strong 0.9 per cent, the annual growth figure (from March last year to March this year) was just 2.3 per cent. That’s evidence of an economy stuck in first gear. Growth this low will not produce enough jobs. Unemployment, already at decade-high levels, seems certain to ratchet upwards.

And yet Joe Hockey told Parliament yesterday that these were a “terrific set of numbers” that proved that those “talking about recession and dark clouds on the horizon” are “clowns.”

The truth, unfortunately, is almost the reverse. Australia’s economic outlook remains subdued at best, and recessionary at worst.

Hockey doesn't think there is a bubble either. "If you look at what happens around the world, bubbles burst in real estate where there is too much supply," he said today. "We are a very long way from that in Australia."

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.