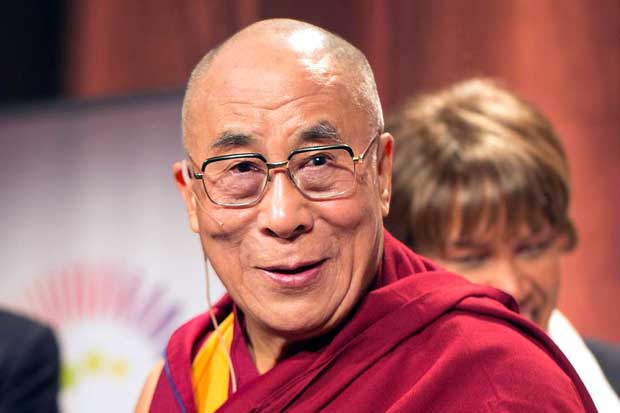

A month shy of his 80th birthday, this week the Dalai Lama is returning to Australia for a much-anticipated series of public talks and Buddhist teachings.

But while the revered spiritual leader of Tibet remains as popular as ever in Australia and around the world, collectively we have been turning a blind eye to the enduring struggle in the Dalai Lama’s homeland – a mistake that may yet prove very costly not only for Tibetans but for the wider region including Australia.

Take a fresh and broader look at Tibet and we soon see that this unique land lies at the very heart of the great challenges of the Asian century. Mineral rich, the headwater of Asia’s great rivers, and sandwiched between great rising powers, what happens in Tibet affects the security, stability and environmental sustainability of vast swathes of the planet.

More than a half-century after China seized control of the strategic mountainous country, Tibet remains wracked with staggering inequality and worsening environmental challenges. Tibetans in many areas continue to face systematic oppression from aggressive and paranoid authorities.

To understand why Tibetans, continue to courageously resist China’s rule – , even though a majority are too young to remember a free Tibet – we need to understand not only the strength of the Tibetan spirit, but also the heavy-handed and ultimately self-defeating strategies through which Beijing has sought to reshape Tibet.

China’s rapid program of industrialisation and urbanisation may be filling the coffers of a growing immigrant Chinese population but has left many Tibetans significantly worse off. The forced displacement of Tibet’s nomads and farmers has destroyed livelihoods, broken communities and exacerbated Tibet’s worsening environmental challenges.

Instead of addressing the understandable grievances, China has continued to imprison dissidents, ramp up surveillance, implement martial law, and, perhaps most insidiously of all, sow mistrust and division among Tibetans.

Maintaining control of Tibet has become a costly exercise for Beijing, both financially and for its international standing. To understand why China clings so hard to Tibet, we need to understand a little more about the region itself. Control of Tibet means control of much of Asia’s water and access to trillions of dollars of mineral resources to fuel China’s burgeoning economy, from copper to lithium.

Control of Tibet also means controlling the border with India, Asia’s other waking giant.

Yet for all its undeniable environmental, cultural and strategic importance, in Australia Tibet suffers from a false perception of a niche and faraway issue, too easily swept aside by the seemingly more pressing challenges of the day. Coupled with fear of diplomatic repercussions and weariness at lack of progress, it has been some years since Tibet rose high on the foreign policy agenda.

This may soon change as China puts the pedal to the floor on a massive program of dam building, and as climate change brings the environmental significance of Tibet into sharper focus. As Asia’s great rivers are parched by the melting of Tibet’s glaciers, and as more Chinese dams and diversion projects impact on flows in downstream countries, water politics across south and east Asia might be about to get a whole lot more heated.

Thankfully, solutions exist. For decades the Dalai Lama, just as he has travelled the world to talk about compassion and environmental responsibility, has reached out to China with a compromise solution based on a meaningful autonomy for Tibetans within the People’s Republic of China. Whether it is through independence or this “middle way”, a long overdue resolution of the Tibetan situation would not only restore basic cultural and religious freedoms and dignity to Tibetans but, just as importantly, ensure the knowledge and experience of Tibetans be brought properly to bear on the future development of Tibet.

The Tibetan people, who for millennia lived sustainably on the roof of the world, have a vast store of knowledge and experience in managing Tibet’s environment. Traditional nomadic pastoralism ensured the health of Tibet’s grasslands, an important carbon sink. Allowing Tibetans control over their own future is not only a matter of rights and justice, and closing the gap between Chinese and Tibetans. It is part of solution that ensures the more sustainable and responsible management of this critically important region, a region on which so much of the world depends.

Over the next weeks as the Dalai Lama turns 80, thousands of Australians will rightly be extolling his profound teachings on kindness, his contributions to interfaith understanding, championing of non-violence, bringing together of Buddhist scholars with western scientists, and innumerable other contributions to today’s world.

But if we really want to give the Dalai Lama a birthday present, let’s start speaking up about Tibet.

* Dr Simon Bradshaw is a Director of the Australia Tibet Council and a campaigner on climate change and human rights issues. Simon has spent several years researching environment protection and development in Tibet, including the role of indigenous knowledge and the traditional rural economy.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.