It’s been 18 long years since the Bringing Them Home report was tabled in Parliament. To commemorate this, Aboriginal communities and organisations across the country today hold events and speeches for 'National Sorry Day'. But despite the significance of the day, it fails to make a mark on the consciousness of the nation each year.

Since the apology to the Stolen Generations in 2008, the landmark report has been pushed further from the political agenda, replaced with empty words and political rhetoric about “healing”, which conveniently bypasses the actual need for “justice”.

If you thought “sorry” was the hardest word, you should try mentioning “compensation”. An apology was only ever intended as one part of full reparations, and one of those planks included compensation.

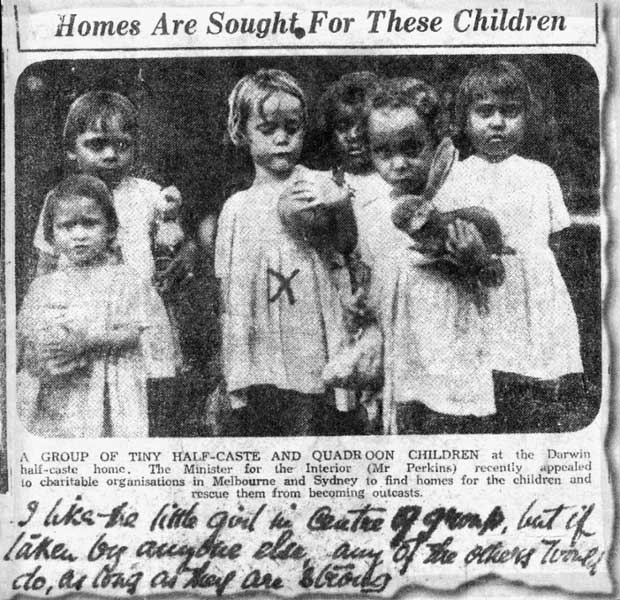

The Bringing Them Home report interviewed more than 500 survivors of the Stolen Generations, and through their testimony told the tragic secret history of the country, where “between one in three and one in 10 Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and communities” between 1910 and 1970.

It told of their pain and their heartache of being separated, and how it would go on to affect them for the rest of their lives.

One of the first pieces of testimony quoted in the report came from Victoria:

“Our life pattern was created by the government policies and are forever with me, as though an invisible anchor around my neck. The moments that should be shared and rejoiced by a family unit, for [my brother]and my mum and I are forever lost. The stolen years that are worth more than any treasure are irrecoverable.”

There are other irrecoverable years spanning the last two decades. While the report delivered 54 recommendations, most of them were lost in the highly-charged political debate over just one of them: a national apology.

Prime Minister Kevin Rudd delivered on a long-standing ALP promise to apologise following the outright offensiveness of John Howard, who steadfastly refused to do so. When Rudd said sorry on his first day of Parliament, Howard refused to attend – he was the only living Prime Minister not there.

But while it is likely any ALP Prime Minister would have delivered an apology, Rudd made embarked on a concerted effort to capitalize on it politically, while at the same time continuing the NT intervention, and rolling out the ineffective Close the Gap initiative (the gap is widening, not closing). Notably, Rudd had precisely nothing to say while the rates of Aboriginal child removal continued to rise every year despite promising in his speech “a future where… the injustices of the past must never, never happen again.”

In fact, since Rudd said sorry, the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care has risen by 65 percent nationally.

It’s a national crisis because Aboriginal children who are taken from their families are more likely to end up in juvenile detention, and then jail as adults. The links between child protection and criminal justice perpetuate a vicious cycle that rips Aboriginal families apart.

But it is not just the fact the days of the Stolen Generations are happening again.

The emphasis on “sorry” on “National Sorry Day” also overshadows the deep need for justice in communities across the country. A key part of that justice – and a fundamental human right – is full reparations.

In the lead up to the national apology, Rudd said with force, “We will not, under any circumstances, be establishing any compensation arrangements or any compensation fund. Absolutely blunt on that.”

Blackfellas across the political divide were split – while the apology was undoubtedly important for healing, any political capital to push for full reparations, including compensation, and the rest of the recommendations, would be lost in the goodwill of symbolic words.

Noel Pearson correctly predicted at the time “blackfellas will get the words, the whitefellas will keep the money. And by Thursday the Stolen Generations and their apology will be over as a political issue.”

And for the most part, it is. Tasmania is the only state that has set up a compensation scheme for Stolen Generations victims. A private members bill to set up a compensation fund in South Australia stalled in the state’s Parliament earlier this year.

But that is all. Aboriginal people have continually seen downright hostility to the idea of full reparations.

Earlier this year, the Supreme Court ruled that Donald and Sylvia Collard and seven of their children, would be forced to repay costs after losing a “test case” for compensation. The ABC reported the costs could run to the tens of thousands of dollars.

Aboriginal Legal Service of WA CEO Dennis Eggington was livid.

“Whether it’s to the Collard family, or to future litigants who feel they’ve been treated unfairly, or the duty of care has been abandoned by the Government, to me it’s a very clear message: ‘Don’t come after the Government because we will continue to protect our so-called innocence in all of this,’” Mr Eggington told the ABC.

And it’s not just in Western Australia. The first Stolen Generations victim to win compensation – Bruce Trevorrow, who was stolen from his parents when he was a baby – passed away before learning the outcome of the South Australian government’s appeal against his victory. For the record, the SA government lost, showing that setting up appropriate compensation funds is much more appropriate than taking Aboriginal people to the courts.

But all this is prefaced on the sad fact that as justice for members of the Stolen Generations grows distant on the horizon with every passing year, our old people are passing away. Many of them will never see compensation, and remain forced to accept whatever crumbs are thrown their way by the very governments that actively harmed them.

Some of these crumbs fall off the table of politicians, who turn up every year at National Sorry Day events and wax lyrical about the resilience of Aboriginal people, while avoiding talk of compensation.

Or failing to mention the sky-high rates of child removal in Aboriginal communities.

There are many things to be sorry about on National Sorry Day each year – and this is surely one of them.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.