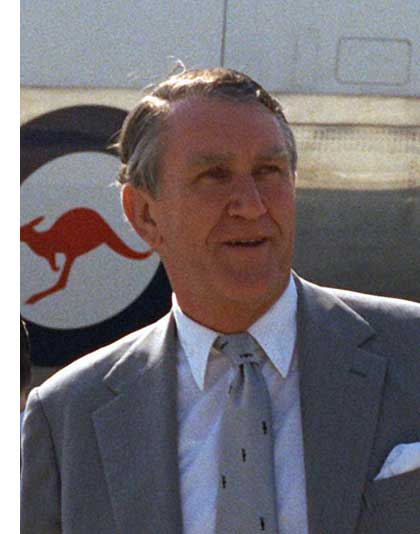

Malcolm Fraser died this morning, aged 84.

The 22nd Prime Minister of Australia governed the country for seven years, taking office after Gough Whitlam’s 1975 dismissal and losing it to Bob Hawke in 1983.

Fraser was one of the giants of his political generation, a man first elected to parliament in 1955. He represented a type of conservative politician than has almost vanished now: an Oxford-educated patrician grazier, seemingly born to rule.

Fraser was born into the Victorian squattocracy, the scion of a family of high-minded conservative tendancies. Fraser’s grandfather, Sir Simon Fraser, came out from Nova Scotia in the gold rush, found fortune in the railways, and bought himself a handsome spread in Victoria’s western districts. Fraser became a pillar of the Bartonite conservatives, serving many terms in Victorian parliament and the Australian Senate.

Young Malcolm was marked out early for political favour. Sent to Oxford in the grim post-war years of the early 1950s, Fraser studied the classical liberal triad of politics, philosophy and economics at Magdalen College, before returning to take up a seat in parliament. He was just 25-years-old.

The Oxford of the early 50s was a stuffy, dowdy place. C.S. Lewis taught at Fraser’s college, while he worked on his Christian fantasies in his spare time. Britain struggled with crippling war debts; rationing was still in place. Politically, Britain was ruled by what has come to be known as the “Butskellite consensus”: an amalgam of the moderate views of Labour’s Hugh Gaitskill and the Tory R.A. Butler, in which a redistributive state accepted trade unions, constructed cradle-to-grave welfare, and unashamedly played a role in industrial development.

Fraser’s politics were shaped by this moderate conservatism, and continued to develop during the long reign of the Menzies government. Like his leader, Fraser was a small-l liberal who believed in national development, personal liberty and conservative social values. He was anti-communist, of course, but his early speeches were about the prosaic matters of agricultural development and the value of transport infrastructure.

In 1956, for instance, Fraser gave a radio talk to his western Victorian constituents about the value of the CSIRO. It’s hard to imagine a politician of the contemporary Liberal Party, so viscerally antipathetic to science, giving the same speech today.

Not that Fraser was without big ideas. In particular, he believed in a big Australia. His inaugural speech to parliament was all about immigration: Fraser looked forward to a nation of 25 million souls. “I am sure that I shall live to see the day when we shall have 25,000,000 people in Australia and then we shall be able to look the world in the face far more boldly and play a more effective part in the maintenance of world peace and freedom,” he said.

Economically, Fraser was a moderate who believed the state had a role to play in development, and who became uneasy with the rightwards shift of economic thinking represented by his future treasurer, John Howard. The Australian Financial Review’s Geoffrey Barker records that “at Oxford, Fraser once told me, his generation of students believed that Keynes had solved the problems of economics and that after the traumas of the depression of the 1930s and the second world war it would be possible to build a better and fairer world.”

As a minister in the post-Menzies era, Fraser became best known as a hawkish Defence Minister. He enthusiastically prosecuted the case for the Vietnam War and for conscription – a tremendously divisive social issue. This reminds us that in the prime of his career, Fraser was an abrasive and combative figure who rarely shrank from the rough and tumble of the political fray.

Fraser was a schemer and a plotter, quite capable of destabilising his own government. In 1971, he resigned from the cabinet of John Gorton in a move calculated to undermine the sitting prime minister. When Gorton was rolled for Billy McMahon, McMahon rewarded Fraser with a seat in cabinet, giving Fraser the imprimatur of a kingmaker. It didn’t help the Liberal Party at the next election, however, when voters turned against the hapless McMahon in favour of the visionary program of Gough Whitlam.

Of course, it is Malcolm Fraser’s role in the downfall of the Whitlam government that has forever marked his biography. After several years of backroom manoeuvring, Fraser bested Billy Sneddon for the Liberal leadership in March 1975.

It was an auspicious time to become opposition leader. The Whitlam government was on the nose, fighting a nasty inflation spike brought on by the 1973-74 oil crisis. A string of integrity scandals, most notoriously the Khemlani loans affair, had also damaged the standing of the government.

Fraser seized the opportunity presented by the Coalition’s control of the Senate to frustrate the Whitlam government’s legislation. Critically, he took the unprecedented step of blocking supply. By refusing to vote for the government’s appropriation bills, the Coalition threatened to shut down the entire federal government. It was a ruthless move from a politician with a steely nerve.

On 17 October 1975, the Senate deferred the appropriation bills, blocking the government’s supply of cash. This sparked the constitutional crisis of 1975, and lit the fuse that exploded beneath Whitlam a month later. In a series of brilliant but unprincipled moves, Fraser cajoled the vain and egotistical Governor-General, John Kerr, into dismissing the Whitlam government and appointing Fraser as caretaker.

The subsequent double dissolution election was won convincingly by the Liberal Party, confirming Fraser as Prime Minister. He would rule for the next seven and a half years.

It was a dazzling tactical success, but one that would forever stain the office of Governor General, and gnaw at the foundations of Australian democracy. Fraser had achieved the ultimate prize, but the price was to bring the constitution of Australia into disrepute, and to forever tar his administration with a taint of illegitimacy.

But if Fraser came to office in a blaze of insurgency, he would rule in a more subdued and minor key. He abolished a few of Whitlam’s signature achievements, such as universal healthcare, but in the main he kept much of the Whitlam legacy in place. The sweeping reforms enacted in the previous three years – from liberalising divorce to support for the arts – proved too popular to roll back. In particular, Fraser kept most aspects of the Whitlamite legacy in education and social policy, maintaining the welfare safety net and most of Whitlam’s liberal social reforms.

Fraser embraced Asian immigration, land rights and many aspects of modern Australian human rights law. He created the Special Broadcasting Service, a signature achievement. He campaigned against apartheid and made a critical commitment to welcome refugees displaced by the wars in south-east Asia that he himself had prosecuted as Holt’s Defence Minister.

But it was the economy that would prove his nemesis. As the post-war Keynesian settlement broke down in the wake of the oil crisis, Australia’s economy began to stagnate. High tariff barriers were no match for a rapidly deteriorating global situation. Policymakers continued to struggle with inflation. The government’s response was a series of austere budgets. Prices were eventually tamped down, but at the cost of high interest rates and rising unemployment.

The resultant atmosphere of economic decline felt very different to the glory years of economic growth of the 1960s. A sharp recession in 1982-83 proved the death knell for Fraser’s government, as a triumphant Bob Hawke rode into office on the back of 10 per cent unemployment and widespread dissatisfaction with the Liberals' handling of the economy.

Future Liberals would look back on Fraser’s government as a lost opportunity for economic reform; the next Liberal government under John Howard would embrace very different social and economic philosophies.

In his later years, Fraser would part ways with the Liberal Party, criticising many of its policies and eventually resigning his membership. It’s a measure of the radically different nature of modern Australian politics that many of Fraser’s political views today seem closer to those of Labor, or even the Greens, than of his once-beloved Liberal Party.

In this way, his death will be seen as a litmus test of the slow rightwards drift of Australian conservatism. Did Fraser drift left, or did the Liberal Party drift right? It was both. In the 2000s, Fraser emerged as a strong voice of tolerant liberalism that seemed increasingly at odds with the dog-whistling xenophobia and rampant pro-business pandering of the party of Howard and Abbott.

Fraser was rightly horrified by the brutal way Australia now treats seaborne asylum seekers, and his support for a moderate and socially-aware conservatism now seems divorced from the savage illiberalism of the contemporary Liberal right wing.

Fraser’s death is therefore an opportunity to reflect on the passing of a key figure in modern Australian politics, and a signpost to the strange mutation of political views in the party he once led. It is difficult now to imagine a Liberal politician hailing from a farming district, a parliamentarian both conservative and in support of scientific research and free and open immigration.

In a strange twist of fate, therefore, Fraser’s true legacy for Australian democracy may instead be his tactical brilliance during the Dismissal – the Machiavellian but ultimately empty belief in power, by any means and at any cost.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.