When are protesters justified in disrupting a public event? Can they legitimately do so in the name of freedom of speech? What aspects of the context change the rights and wrongs of a disruption? These kinds of questions are among the most delicate, complicated and important that protest movements and progressive activists face, but they are rarely discussed in depth.

Last week, a protest during a public talk at Sydney University by Richard Kemp, a retired colonel of the British army and a longstanding apologist for the Israel Defence Forces, provided a clear test case.

Kemp has regularly been criticized for his propagandistic defence of Israel’s brutal state-sanctioned murder of Palestinians, a defence he proffers in the media, in public talks, and in a submission to the UN.

Referring to last year’s war in Gaza, responsible for the deaths of over 1,500 Palestinian civilians, Kemp described Israel as “world leaders in actions to minimise civilian casualties”. He has also reiterated his belief, originally expressed in the context of the 2008-9 Gaza war, that “no army in the history of warfare had taken greater steps than the IDF to minimise harm to civilians in a combat zone”.

“All Palestinian civilian casualties in this conflict,” he has claimed “result ultimately from Gaza terrorists’ aggression against Israel”.

Kemp was in Sydney on a speaking tour organized by the United Israel Appeal, an organisation that “works to further the national priorities of the State of Israel and Israeli society”. I attended his lecture, ‘Ethical dilemmas of military tactics in relation to recent conflicts in the ME: Dealing with non-state armed groups’ as a member of Sydney Staff for BDS, an organization of Sydney University employees campaigning for our institution to cut its ties with Israeli universities that support the occupation.

Members of Sydney Staff for BDS were present outside the lecture-theatre in the Carslaw building at which Kemp spoke, distributing leaflets to the audience as they went in; several of us, including me, attended the lecture and asked questions of Kemp at the end.

Speaking for myself, I was heartened by the protesters’ disruption of the lecture, and, although I did not directly participate in the protest – and certainly did not “lead” it, as Kemp has inexplicably claimed – I supported, and support, the protesters’ right to intervene in the nonviolent way they did.

In The Australian, Gerard Henderson has accused people like me of hypocrisy and intolerance.

Diagnosing what he takes to be a characteristic attitude of the Left, he has criticized anyone who “believes that anti-Israel demonstrators have a right to disrupt lectures provided no physical harm is caused, but does not advocate such behaviour for their own functions”.

This appeal to freedom of expression is, of course, a standard response the Right makes to disruptive protest, by no means limited to the present issue.

Other writers in The Australian and elsewhere, and Paul Sheehan in The Sydney Morning Herald, have offered the same argument – usually with flagrant disregard for the facts now on the public record, thanks to Michael Brull in New Matilda.

Henderson’s pedestrian reasoning would be much improved if he drew some basic distinctions. Of course, I do not “advocate” that anyone disrupt a function that my own group has organised. Is there, in fact, anyone who would advocate such a thing?

However, while I don’t invite people to come along and interrupt my functions, I recognise that anyone has the right to do so, peacefully, just as these protesters had the right to make their views known during Kemp’s talk. In other words, I do not believe that any third party has the authority to prevent people making that interruption. The question is not one about what actions one has the right to undertake, but about what is right – in other words, questions of what actions one should and should not undertake.

Once this elementary distinction has been made, it’s clear that there is no hypocrisy or inconsistency whatsoever in what Henderson takes to be the standard position of the Left, either over Israel or over any other contentious issue. Many left-wing people, I believe, would defend the proposition that protesters have the right to disrupt any kind of public speaker, but that only disruptions of certain public speakers are right.

Applied to the present case, this means that anyone has the right to disrupt either a pro- or an anti-IDF speaker, but only interruptions of pro-IDF speakers are actually justified.

To explore the issues in the detail they need, let’s take the two questions I’ve distinguished – “what actions do I have the right to undertake?” and “what actions is it right for me to undertake?” – in order.

No right not to be interrupted

First, it should be obvious that there is no general right to speak without being interrupted. No-one, including Kemp, has the permanent right to speak without being interrupted at a public event. Conversely, protesters always have the right to interrupt. Interrupting someone may, depending on the situation, be unwise, unreasonable, impolite, or wrong – or, conversely, necessary or desirable – but there is no inalienable right not to be interrupted. There are many occasions on which you are perfectly entitled to interrupt me, and vice-versa.

Many people in the Kemp lecture made it clear that they agree: during the questions both Jake Lynch and I put to Kemp at the end of his talk, people interrupted us, and in some cases tried to shout us down.

The University of Sydney itself has repeatedly shown – scandalously – that it believes it has the right to prevent people speaking on campus: in 2013 it tried to ban a campus appearance by the Dalai Lama, and last year, as the protesters at Kemp’s lecture pointed out, it prevented Uthman Badar, Hizb ut-Tahrir’s media spokesman, from participating in a Q&A session sponsored by the university’s Muslim Students’ Association.

Freedom of expression is always conditional on what is being expressed

There is, then, no right to speak without being interrupted. Protesters aren’t violating some inalienable right when they interrupt a speaker. But the fact that there’s no absolute right not to be interrupted doesn’t mean it’s always right to interrupt people.

Whether it’s right to interrupt someone in a particular situation depends on many considerations. For example, I may be right to interrupt you, or prevent you from speaking, if you are about to unwittingly say something highly harmful to either yourself or someone else, or if you are about to incite others to an act of violence, or if I believe that the consequences of your speaking are ones that you would not wish to experience.

The relevant question, then, is under what kind of circumstances is it right for protesters to interrupt a speaker.

There are many circumstances where a protest like the one that occurred during Kemp’s address would not be criticized. No-one, for instance, would object to protests interrupting a public talk by a neo-Nazi, or a proponent of slavery or of child-abuse. As these examples show, most small-L liberals would accept that there are some kinds of public expression which should not go uninterrupted at the source.

They are right to accept this. The vast majority of traditional liberals admit that cases of incitement – a Ku Klux Klan member, for instance, whipping up a crowd to murder blacks – are a clear exception to freedom of expression.

This exception’s existence clearly demonstrates that even for traditional liberalism, freedom of speech is conditional on the content of that speech: there comes a point where the content of what is said is so extreme that the speaker no longer enjoys the right to express it.

The principle that comes out of this is that disrupting someone’s speech is justifiable when the speech itself violates other norms – like the necessity to prevent hate-crimes, respect for which is more important than the speaker being allowed to continue uninterrupted.

Free speech is only important if it promotes human flourishing

As the case of incitement makes clear, freedom of speech is not an end in itself, but only holds in-so-far as it promotes certain other things we find desirable.

Since preventing the execution of hate crimes is more important than allowing a Ku Klux Klan member to speak without interruption, liberals readily acknowledge that there are limits to the freedom of speech in this kind of case.

Implicit in most justifications of free speech is the idea that it is fundamentally progressive – that it is, in other words, a precondition for human flourishing and for the construction of a just society.

There are two reasons for this assumption. The first is the idea that, to quote John Stuart Mill, “only through diversity of opinion is there, in the existing state of human intellect, a chance of fair play to all sides of the truth”. It is only if all individual opinions can be freely aired that public opinion can be exposed to, and then adopt, the opinion that is just and true.

On this conception, political debate has the characteristics of a free market: everyone should have the chance to speak their mind, and competition between ideas will favour the best ones, which thereby become the basis of collective decisions made through the usual channels of representative government.

Disruptive protest is consistent with the principles of free speech

It is perfectly possible to accept this rationale for freedom of speech, and to believe that there are circumstances where it is right to disrupt someone’s exercise of that very freedom.

How might this apply in the case of Kemp? Kemp was appearing in order to justify the military acts of a brutal settler occupation. He was therefore contributing to an attempt to legitimate the denial of democratic freedoms and the ongoing oppression of the entire Palestinian people, who have regularly found themselves on the receiving end of IDF bombs and bullets.

Kemp’s propagandizing does not serve human flourishing. He is an apologist for war, and for the IDF as an instrument of the settler colonialism of an antidemocratic state determined to withhold basic rights from large numbers of people.

As such, his speech aims at the dismantling of the very democratic freedoms among Palestinians which commitment to the principle of free speech is supposed to embody.

Challenging Kemp’s right to hold the floor is a strong assertion that his views violate basic ethical norms, in a way that civil society should simply find as unacceptable and intolerable as, for instance, promotion of slavery. No-one has to agree with that assessment – I, for the record, do agree with it – but it is up to protesters to decide for themselves how prejudicial to a society’s flourishing a speaker is, and, consequently, how strenuously they should disrupt them.

Disruptive protest turns facts into issues

It is often objected to this kind of position that the best way to counter objectionable political views is to argue against them, not disrupt them.

The leaflets distributed to the audience by members of Sydney Staff for BDS, and the questions we asked of Kemp at the end of his talk, had exactly this intention.

The protesters, however, made a different, and entirely justifiable, tactical decision. The rationale for it is easy to imagine: facts and argument have, on their own, proven singularly impotent as drivers of positive change in Israel-Palestine.

The intolerable oppression of Palestinians needs an assertive protest movement that is ready to disrupt the expected order of things to bring it to the attention of the Western public. Only when what is happening in Gaza and the West Bank is forcefully and, if necessary, disruptively asserted does it stop being merely a fact and become an issue, something which impinges enough on public consciousness to force people to take a stand.

This strategy – using disruptive protest to turn facts into issues – has been the rationale for protest movements forever. Consistently, the international BDS movement is predicated on the idea that a logic of nonviolent pressure exerted against Israel in favour of Palestinians’ democratic freedoms is the most powerful tool available to bring justice to this part of the Middle East. Palestinians have waited decades for facts and dialogue to win the argument for them on their own through the international “peace process” – in vain.

Protesters have freedom of expression too

The second reason for which freedom of expression is thought to be progressive is the intuition that constraining someone’s ability to speak seems like an affront to their intrinsic autonomy. As free people, we are surely justified in the expectation that we will not be prevented from saying what we want. Respect for people’s inherent liberty should prevent restrictions on their liberty of expression, just as it should prevent restrictions on their liberty of movement.

This justification is also compatible with disrupting public events. Protesters have freedom of expression too. Just as Kemp has the right to speak in a public space, so too did the protesters have a right to respond in the way they saw fit.

Kemp’s sponsors at the university could easily have put on a private, invitation-only function, called for RSVPs to the talk, or asked Kemp to deliver a guest lecture in a politics course. Had they done so, they would have had every right to keep protesters out.

Instead, they chose to host Kemp at a lunchtime talk in a public venue which, appropriately, protesters were not prevented entering. In this kind of space, anyone has the right to intervene. Doing so in the way the protesters did might be impolite, or brash, or unusual – but there is nothing wrong with it.

How to react to the public expression of a political opinion is as much an expression of human freedom and autonomy as is the original act of expression itself. Who gets to hold the floor in a public appearance is a matter to be negotiated by the speaker and the audience. The speaker only has a right to the floor for as long as the audience tolerates them.

It makes no difference to this argument to complain, as Henderson has done, that the protesters intervened before Kemp had said anything about Israel-Palestine. Kemp has made his name as an IDF-apologist and is only here as the guest of the United Israel Appeal.

His talk, which was only publically advertised on J-Wire, was clearly not an academic occasion, since, as a search of the University of Sydney website reveals, it was not advertised in any university publication.

As a result, it did not benefit from the norms governing academic lectures delivered in the context of research or teaching.

Instead, the audience comprised members of the public, some young people – apparently, students – and a handful of academics. Alex Ryvchin, Public Affairs Director at the Executive Council of Australian Jewry, was also in attendance.

With Palestine preparing to enter the International Criminal Court on April 1, the occasion gave every appearance of a propaganda exercise for Israeli military policy, using the venue of the University of Sydney to confer intellectual and institutional respectability on it.

“Positive” and “negative” freedom of expression

Isolating the disruption to the speaker as the only morally relevant aspect of protest ignores the fact that ‘freedom of expression’ has two dimensions.

The first is the obvious one – a speaker’s, in this case Kemp’s, freedom not to be interrupted.

This freedom – sometimes called “negative freedom” – is what protesters violated. But, as they made clear, they did so in order to promote another kind of freedom: the “positive freedom” of the millions of Palestinians whose fundamental liberties, including liberty of expression, are regularly denied by Israel.

The protest was an attempt to assert the moral urgency of support for Palestine, and a statement that, in the protesters’ view, this urgency trumped Kemp’s right to hold the floor uninterrupted.

Once again, you might not agree with that judgement, but this is just a consequence of the fact that differences of opinion will always exist over what values should be respected.

If you object strongly enough to what is being said at a public talk, you also are justified in trying to disrupt it.

Freedom of expression, censorship and justice for Palestine

It’s sometimes claimed that the freedom of speech principle is most valuable exactly to supporters of minority or dissident views, like Palestine supporters, since they’re the ones whose avenues for public expression are most likely to be blocked.

Given the difficulty of making pro-Palestine arguments publicly, activists simply can’t afford to violate others’ freedom of expression, since doing so would mean undermining the strongest principle to which they can appeal in favour of their own right not to be censored.

The freedom of speech card, however, is just one of several strategies which Palestine supporters can play to make the case against the censoring of their views.

Attempts have recently been made to censor pro-Palestine speakers in universities in Paris, Rome and Southampton, mostly successfully. What is the way forward for Palestine supporters in these contexts? Not to assert the abstract, procedural principle of freedom of speech and simply hope that our ideological opponents will respect it. It is very clear that they usually won’t.

Instead, a more effective strategy involves building a coalition of voices, on the ground, prepared to press the case both for Palestine, and for the censorship to be lifted – not in the name of the abstract ideal of freedom of speech, whatever the content of that speech, but in the name of the necessity of concrete justice for Palestinians.

This work of coalition building doesn’t need public meetings to be carried out: it is achieved by conversations, petitions, private meetings, and other means which don’t risk being censored.

The creation of a bloc of Palestine supporters like this is, in any case, an independently desirable outcome.

Holding public meetings which risk being censored isn’t the only way to reach people about Palestine. In a political environment where the balance of forces makes censorship of such meetings a real possibility, it probably isn’t even the most effective, since the other side will have more opportunities to counteract the pro-Palestine message with its own propaganda.

In this context, one-on-one conversations and the other means I’ve mentioned, conducted over a period of time, may well be a better strategy.

In this article, I’ve tried to justify the kind of disruptive protest that occurred during Kemp’s talk at Sydney, in the belief that disruptive protest is rational, effective, and compatible with widely shared beliefs about freedom of expression and individual autonomy.

The idea that views like Kemp’s should, where possible, be disrupted when aired in public, is compatible with the stronger “no platform” policy often associated with the radical left. One does not, however, have to be a radical leftist in order to accept the appropriateness of disruptive protest in some contexts.

The underlying assumptions of mainstream liberalism and, specifically, the idea that freedom of speech is the expression of personal autonomy, and a means to the end of a more just society, provide protesters with the resources they need to justify the kind of political intervention that was made at Kemp’s talk.

Supporting the right to protest disruptively is not the same as endorsing a higher authority’s right to censor political views.

Governments should not decide who is and is not fit to speak to the public. Only police-states take those decisions into their own hands.

Similarly, institutions like universities have no business intervening in the course of political meetings for which they provide the venue.

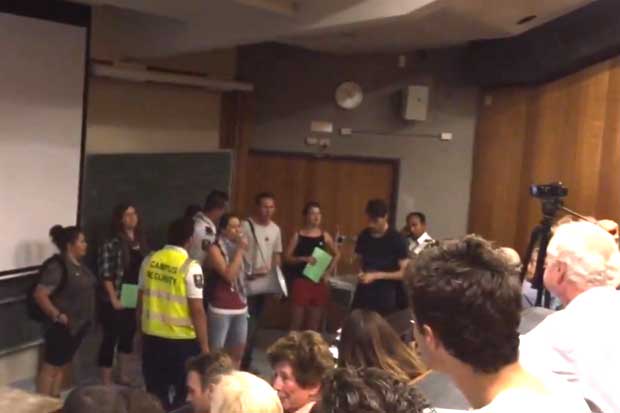

Violently ejecting the protesters from Kemp’s talk, as university security did last week, amounts to taking sides in the open and legitimate exercise of political debate.

This is not only disgraceful in itself, it is an affront to the idea that universities should be places where differing political views are confronted.

This confrontation will only rarely take the form of disruptive intervention. But since this intervention is itself an expression of the very political freedoms which universities claim to promote, they have absolutely no business restricting them.

* Reader's are reminded to observe New Matilda's rules for commenting. Debate can be passionate, but should not be abusive or insulting. Commenters who seek to incite racial hatred will have their accounts deleted without notice.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.