The NSW Planning Assessment Commission, an independent body set up to approve major developments, has advised the Baird government to consider “relocating” the entire village of Bulga and its 350 residents, in the Upper Hunter Valley of NSW, to make way for a coal mine.

It’s the last stage of a five-year battle that has seen the NSW government work hand-in-glove with Rio Tinto to get its Mount-Thorley Warkworth Mine expansion approved.

The government has teamed up with the mining giant to fight Bulga residents in two court cases. They lost both, and the courts rejected the mine expansion because it would ultimately destroy Bulga.

But after the first court refusal, then Premier Barry O’Farrell met with a senior Rio Tinto representative and the law was changed to circumvent the courts and pave the way for the approval.

Now, the same mine expansion is being rushed through at break-neck speed, only under the new rules, which have removed the community’s right to have approvals reviewed on their merits by the courts.

The 200-year-old village is inland of Newcastle, about 20 kilometres from Singleton. It has a pub, cafe-come-petrol-station and a quaint old bridge on the road in, which was built in 1912.

If Rio and the government get their way, it will have a coal mine three kilometres from people’s homes. The project will also destroy 13 per cent of the endangered Warkworth Sands Woodland ecological community and sacred Aboriginal sites of high significance.

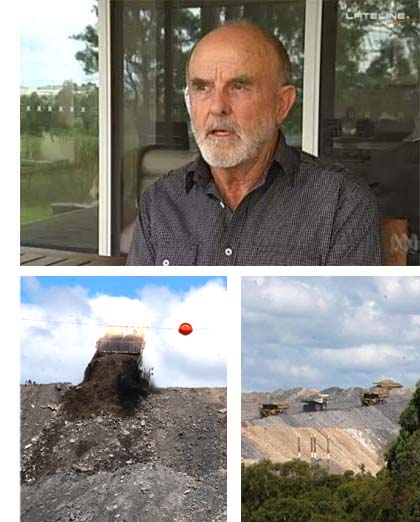

John Krey – who acts as a spokesperson for the community group resisting the mine, the Bulga Milbrodale Progress Association – bought land in Bulga in 2003.

Like many others the Kreys relied on a key condition of an earlier expansion, also in 2003, which specifically prohibited the mine expanding west towards Bulga over an area known as Saddleback Ridge.

“The main concern for Bulga residents is the fact that they are going to mine through Saddleback Ridge, an area that back in 2003 it was agreed would never, ever, be mined,” John Krey told New Matilda.

“It was supposed to be preserved in perpetuity.”

For Bulga residents, Saddleback Ridge has been a shield from the worst of the dust, noise and light produced by the existing MTW mine.

The 2003 condition was backed by a private Ministerial Deed of Agreement which required Rio Tinto to rezone Saddleback Ridge for conservation in order to make good on their promise that it would be off limits to open-cut mining.

But the deed was kept out of public view, never dated, and never enforced.

Now, it has now been changed twice – in 2004 and then during the residents’ legal struggle – so that its only purpose is to invalidate the initial document.

Residents first realised the deed had been trashed, and they’d been duped, in 2010, when Rio Tinto lodged an application to expand westwards to within three kilometres of Bulga.

“When the 2010 expansion proposal was put forward we saw that the village of Bulga would go the same way as the villages of Ravensworth, Warkworth and Camberwell, where the expansion of open-cut mines made their villages un-liveable,” John Krey told New Matilda.

The PAC approved the expansion in 2012, but it noted at the time that “in almost all cases, the mines [in the Hunter Valley]have been approved and the communities have either been radically altered in character or become non-viable”.

Despite this admission, the PAC approval went through because the planning system was already geared towards the economic value of the mine above the social and environmental.

Importantly, the PAC also has to rely on information provided by the consultants who the mining company selects and pays.

The expert, and truly independent, evidence provided when Bulga residents took Rio Tinto to court in 2013 was crucial to the judges rejection of the MTW expansion because it showed-up deep flaws in the reports provided by Rio Tinto.

“Balancing these significant adverse environmental and social impacts against the material economic and social benefits of the project, I consider the project has not been established to be justified on environmental, social and economic grounds,” Chief Justice Preston wrote in his Land and Environment Court judgement.

This ruling, that the project was not in the public interest, was upheld by the NSW Supreme Court of Appeal in 2014.

But it was within weeks of the first court ruling that Rio Tinto started holding high-level meetings with the NSW government to get the expansion approved, documents obtained under freedom of information laws reveal.

A letter, dated three weeks after the first court decision, reveals that the then Premier Barry O’Farrell met with Rio Tinto’s Chief Executive of Energy, Harry Kenyon-Slaney on 2 May 2013.

Wielding ‘commercial in confidence’ legal advice, Kenyon-Slaney lobbied the highest levels of government.

He argued that the options suggested by the Department of Planning and Environment in a string of earlier meetings were “likely at best, to result in litigation being commenced in respect of them, and at worst, [to be]found to be unlawful”.

The bosses of Rio, a letter from Kenyon-Slaney reveals, were very concerned that the mine not being re-approved would create a dangerous new precedent which could ultimately threaten Rio’s decision “to continue to invest in NSW”.

“In our opinion the only option left to secure an outcome that will deliver certainty to the MTW and other major project approvals in NSW is to legislate to validate the decision of the Planning Assessment Commission to approve the MTW Extension Project,” Kenyon-Slaney wrote.

In other words, the system would need to be changed to make the MTW expansion approvable, and a precedent had been set that might embolden communities to exercise their right (at that time) to challenge approvals in the courts.

“This court decision challenged their whole method of assessment,” John Krey said.

“They could no longer do what they were used to doing – approving all coal mines.

“So that’s why – and of course with coercion from Rio Tinto – they all came on board and decided to fight us on it.”

After the first court defeat the government began rewriting the rules to make sure it would never happen again.

They removed the community’s right to have projects reviewed on their merits by the courts, and changed the planning approvals system to make “the [economic]significance of the resource” the “principal consideration” when determining applications.

Then the government again joined forces with Rio Tinto to push the project through at breakneck speed.

Fresh documents, also obtained through freedom of information laws, expose the level of collusion between the Baird government and Rio Tinto to accelerate the project’s second-run.

“Timeliness is of the essence,” one email, sent by Andrew McIntrye the Office of Environment and Heritage’s Regional Manager for the Hunter Valley to a Rio Tinto staffer, makes clear.

“I understand there are various meetings between Rio Tinto and senior levels within government,” McIntyre wrote.

Nevertheless, he requested the “raw data” used by Rio Tinto in key reports which he had criticised in an email earlier that day as totally inadequate.

“We really feel this is prudent to make our assessment robust to external scrutiny,” he wrote.

For legal reasons, the environment group that obtained the documents has not released all of them.

However it is clear that processes which usually take months were being completed in days or weeks, and to a timeline which appears to have been unduly influenced by Rio Tinto.

The changes being discussed are, in large part, designed to address the holes blown in the project’s credibility during the two court challenges.

For residents of Bulga, though, the mine’s expansion will ultimately have the same impacts if it is approved again, because it will still come to within three kilometres of their homes, and remove Saddleback Ridge.

“The current application is very similar to the [2012] Warkworth Extension Project that was refused by the Land and Environment Court,” the PAC noted on Thursday, but due to the “significant legislative and policy changes have occurred since that time” it is once again approvable.

Only this time residents have no right to challenge that approval.

A final decision will be made in the coming months, and despite the PAC requesting more information and placing more stringent conditions on the project, the government is clearly determined to ensure a final approval.

The PAC’s suggestion that residents who want to move be compensated, or the whole village relocated, is as close to an admission that the village of Bulga will be destroyed as that body is really allowed to give.

But residents of Bulga don’t want to be compensated, or relocated. They want the support of their government.

“Why should I have to justify my right to survive here?” John Krey said.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.