Fears over the mining of uranium in NSW have been revived by Alkane Resource’s Dubbo Zirconia Project, which is inching closer to approval.

Alkane Resources has not technically applied to “produce” uranium, but will inadvertently mine uranium and thorium.

The radioactive metals are mingled in the ore body along with rare earths, which Alkane is targeting, like zirconia and niobium. Rare earths such as these are mostly used in the manufacture of electronics, but can be used for other purposes, most notably in the military.

The mine, proposed to be built at Toongi, 25 kilometres upstream on the Macquarie River from Dubbo, has revived arguments over the inherit threats to community health and global security posed by uranium.

Under NSW law it remains illegal to “produce uranium”, but if approved the project will mine material which is between 80-160 parts per million (ppm) uranium and 250-500 ppm thorium, compared to a world average of 3 and 6 parts per million respectively.

Alkane expects the mine to be approved by the end of the year, but Dave Mould, who runs community opposition group Uranium Free Dubbo, says the mine poses an unacceptable danger to Dubbo’s population of 40,000.

The controversial metal could be mined without damaging public health, Dr Gavin Mudd, an environmental engineer with Monash University, told a community meeting in late October.

“My simple approach is that there is a demand, and there’s a need for rare earths for good technologies, as long as we can manage the mines well,” Dr Mudd said.

“Now unfortunately we don’t really have a good example of that worldwide.”

Dr Mudd said it often fell to the community to keep track of mine compliance, but Alkane’s processing models, which would manage radioactive materials, are ostensibly well founded.

There is also concern that the Dubbo Zirconia Project could open the flood gates to a state-wide uranium mining industry foreshadowed in late 2012 by the NSW Coalition government.

Alkane, who has been invited by the NSW government to apply for a uranium exploration licence, “is trying to get the drop on their competitors,” according to Dave Mould.

While uranium mining remains banned in NSW, the 26-year prohibition on exploration was lifted by the state government in late 2012.

The move signalled the dawn of a “new era”, according to then resources minister Chris Hartcher, who said the change in policy would “create an industry” and allow NSW to take advantage of “the resources boom underway in Western Australia, Queensland and South Australia”.

The move continues a departure from Labor’s “three mine policy” which had limited uranium mining since the 1980s until John Howard came to power in 1996.

Western Australia reversed a ban on uranium in 2008 and Queensland followed suit in 2012.

It seems inevitable that NSW will follow in Queensland’s footsteps and, after a temporary exploration-only period, legalise the sale of uranium.

At a community meeting late last month Bev Smiles of the Central West Environment Council addressed the elephant in the room: “The big question now that everybody’s asking is why would you bother exploring for [uranium]if you couldn’t mine it?”

The NSW Department of Planning & Environment (DP&E) would not comment on what additional approvals, if any, would be needed to allow for the mining of uranium, leaving open the possibility that Alkane could bypass the more rigorous consultation involved in initial project approvals.

The Office of Energy and Resources told New Matilda that “any other activity will require additional environmental assessment and approval” but there are concerns that the more rigorous community consultation processes, usually undertaken as part of the State Significant Projects framework during assessments by the DP&E could be bypassed.

Alkane CEO Nic Earner, though, is adamant that the ban was a boon for the company, which he says “is not applying to produce uranium, is not intending to produce uranium and does not seek approval to produce uranium.”

Alkane maintains it has been forced to express interest in mining the Toongi site, which is the largest identified uranium deposit in NSW.

Along with six other selected companies, Alkane has been invited to apply for a uranium exploration licence after participating in an Expressions of Interest process established by the Office of Energy and Resources.

A spokesperson for the company denied the move was a sign Alkane had plans to sell the controversial metal, saying that the move was designed to “safeguard Alkane’s interests in the Dubbo Zirconia Project from third parties”.

“If another company put in an expression of interest for uranium over our tenement, and we did not, then the other company could have the licence to explore and recover uranium from our tenement and interfere with the rare earth, zirconium and niobium development,” the spokesperson said.

Alkane has not yet applied for a full exploration licence, let alone permission to sell uranium, but community concern over the project is growing.

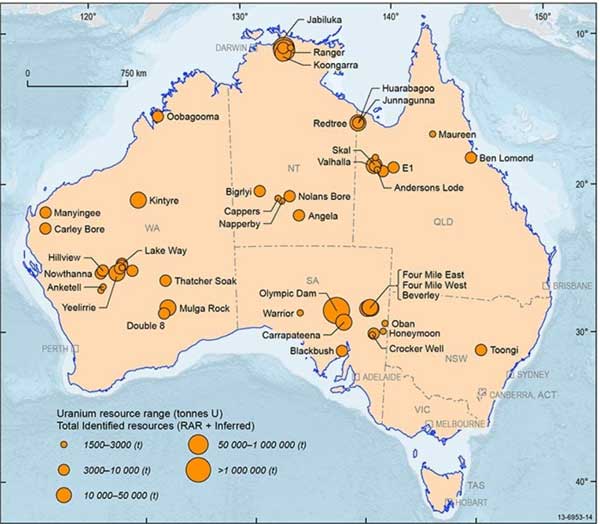

Toongi is the site of NSW’s largest identified uranium deposit, containing somewhere between 10,000 and 100,000 tonnes of uranium, according to government body Geoscience Australia.

The Dubbo Zirconia Project would be the first rare earths elements mine in NSW – a subset of the mining industry that has typically been almost extensively serviced by China. However China has been enforcing quotas for about a decade, partly due to the serious health impacts often associated with rare earths mining.

Over the 20-year life of the project around 80,000 tonnes of “radioactive substance” – uranium and thorium – would need to be “diluted”, according to Alkane’s Environmental Impact Statement.

This “dilution” would require up to 50 million tonnes of other, non-radioactive, materials. Around 7 million tonnes of salt, 2.5 billion litres of ‘liquid residue’ and 2 million tonnes of ‘solid waste’ would remain at the mine site forever, alongside a 40-hectare “final void”.

The process of dilution does not make the materials any less radioactive, according to Dr Gavin Mudd: “Instead of being in the rock, it’s now dissolved into various process solutions, and it’s now somewhere else.”

“Some of it will end up in the salt, some of it will end up in other solid residues, and so on.”

Dr Mudd said Alkane’s engineering work seems to be “fairly robust”, however concerns remain over the long-term security of the displaced radioactive materials.

“In the Department of Planning assessment report…there’s no discussion of the lifespan of this [storage]material. There’s no discussion of who’s responsible for the legacy in the future once the mine is decommissioned,” Bev Smiles said at a community meeting late last month.

“So all the rehabilitated solid waste areas will contain toxic materials and there’s just no discussion of what will happen with this in the future.”

Alkane expects that the mine will receive full approval by the end of this year for its current proposal of 19.5 million tonnes of rare earths and metals over a period of 20 years. However the miner has said that it will likely seek to extend the mine life to 70 years.

The radioactive risk posed by the project is also acknowledged in the terms of reference provided to the Planning Assessment Commission, an independent body which gives advice to the NSW government on major mining approvals.

The PAC terms of reference require it to pay particular attention to “air quality impacts, including any exposure to radioactive material”.

Notwithstanding these and other local risks, the business proposition for uranium is rapidly improving.

Last year the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Nuclear Energy Agency and the International Atomic Energy Agency predicted that by 2035 world nuclear capacity “is projected to grow between … 44 per cent and 99 per cent respectively”.

Australia boasts approximately 35 per cent of the world’s uranium, and the last five years has seen mining or exploration activities burgeoning in South Australia, the Northern Territory, Queensland and Western Australia.

In another sign the industry is set to take off, the Federal Government signed off on a deal in September allowing the export of uranium to India.

The deal has been criticised because India has not has not signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, and as the uranium industry grows so might the opposition which forced the widespread Australian freeze on uranium late in the cold war.

Bev Smiles, who campaigned against uranium in the 1980s, said recent developments around uranium are like “ground-hog day” at a recent Dubbo information night.

“While we’ve got the current federal government debating whether burqas are allowed into parliament because of terrorist activity, the real threat to our security is terrorists getting their hands on uranium,” Ms Smiles said.

After receiving final approval from the state government the Dubbo Zirconia Project will require a federal approval under the Environmental Protection & Conservation Act.

“Even if they get it approved they’re going to have a big fight on their hands,” Dave Mould of Uranium Free Dubbo said.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.