Another asylum seeker has died in custody. We should be honest about it: he died in Australian custody.

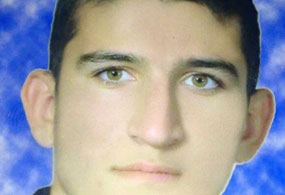

Hamid Kehazaei was a human being – a young man with hopes and dreams. A man who had pains and sorrows. A man who we will probably never know much about.

We won’t know about his family. We won’t know about who he loved, and the people who loved him. We won’t know about what kind of contribution he might have made to Australia.

What we know is that he died. He died in circumstances that could have been foreseen and prevented.

We also know that more people will die in our custody. We know that it is not an aberration, but the result of policy that has been consciously chosen and embraced by both the Coalition and the Australian Labor Party.

Hamid Kehazaei cut his foot. It seems clear that due to the quality of medical care Australia ensures asylum seekers on Manus Island get, Hamid died.

Australia set up the detention centre on Manus Island so that we could send people like Hamid there.

We decided who would go there, and the circumstances in which they would go there.

We decided what life would be like in that centre, and, it seems, we also decided the circumstances that could lead to death in our detention centre.

We also know that Scott Morrison, our immigration minister, thinks that the medical care Hamid received was “outstanding”.

He claimed that those who criticised the standard of care Hamid received were using the situation to “make political points”.

Any rational person with an ounce of decency can understand clearly what happened, and its significance.

More asylum seekers started approaching Australia by boat. The media declared that this was a disaster for Australia. Both major political parties settled on increasing Australia’s cruelty to asylum seekers, in the hope that this would prevent asylum seekers from seeking asylum in Australia.

We could let asylum seekers into Australia and process them in the community, which would be the cheapest and most humane way to deal with them.

Australia could have continued its practice of indefinite mandatory detention of asylum seekers within Australia – already, a cruel and inhumane policy. Instead, we decided to send asylum seekers to places that we could say weren’t part of Australia, and pretend they were no longer in Australian detention.

We would no longer be swamped by asylum seekers. The reason we expected that asylum seekers would stop coming is that we decided to make the life of asylum seekers so awful, that other asylum seekers would know better than to try to come to Australia.

Anyone who wanted to know about how we were treating asylum seekers in offshore detention could know. In April 2013, Bianca Hall reported on a doctor’s impressions of working at Manus Island detention centre.

Dr John Valentine warned that the island lacked desperately needed equipment, and was unfit for the care of children: “The whole time I was there it was just a disaster, medically…. They ought not to be in Manus Island. It's just too remote and the medical facilities are quite inadequate.”

In December last year, David Marr reported on a group of doctors who were shocked at the level of medical care they were made to provide asylum seekers at Christmas Island detention centre.

The doctor’s report revealed:

• asylum seekers are examined while exhausted, dehydrated and filthy, their clothing “soiled with urine and faeces” because there are no toilets on the boats

• patients are “begging for treatment”

• asylum seekers must queue for up to three hours for medication. Some have to queue four times a day

• antenatal care is unsafe, inadequate and does not comply with Australian standards; there is an ultrasound machine on the island but rarely anyone who knows how to use it

• there is a high risk of depression among children and no effective system for identifying children at risk

• basic medical stocks are low; drugs requested by doctors are not provided

• long delays in transferring patients to mainland hospitals are leading to “risks of life-threatening deterioration”.

Let me note that last point again: “long delays in transferring patients to mainland hospitals are leading to “risks of life-threatening deterioration”.

Their concern, in other words, is that the long delay in transferring a patient from Christmas Island to an Australian hospital posed a ‘life-threatening’ risk.

Scott Morrison declined to comment on the contents of the report. I suppose he regarded the publicity as a good thing, given that it might help deter asylum seekers from coming to Australia.

Also in December last year, Amnesty International released a report on Australia’s detention centre on Manus Island.

Graeme McGregor, Amnesty’s refugee campaign coordinator, wrote that “The living conditions in the facility are hot, extremely cramped and poorly ventilated. There is no privacy. The conditions in one dormitory were so bad that Amnesty International considers the accommodation of asylum seekers there a violation of the prohibition on torture and other ill-treatment.”

He also observed: “As the week progressed, we witnessed a string of unnecessary humiliations. The men spend several hours each day queuing for meals, toilets and showers in the tropical heat and pouring rain, with no shade or shelter. Staff refer to them by their boat ID, not their names. Almost all are denied shoes.”

McGregor wrote that the 500 men in the "Oscar" compound each receive only 500mls of water per day, though the recommended quantity is five litres each.

In Oscar, there is one toilet for every 30 men and they are often dirty or broken.

The men are not given enough soap, shampoo, mosquito repellent, washing powder or shaving equipment. Contact with loved ones by phone is limited to two 15-minute calls a week, strictly regulated, often in the middle of the night with no privacy.

Despite the difficulty connecting, men calling their families in remote areas or war zones are given no extra time – when your 15 minutes is up, it’s up.

Like others, he also noted the disturbingly inadequate medical care for asylum seekers: “The facility is unable to provide suitable treatment for men with serious illnesses and disabilities – which include asthma, diabetes, epilepsy, gastroenteritis and dwarfism. Staff told us that they’re struggling to cope with the growing demand for health and mental health services, and they receive no response from the Australian authorities to basic requests which would improve health and sanitation within the camp.”

Inadequate medical care is not the only threat to asylum seekers. Hamid died because of a cut on his foot, but Reza Berati died because he was murdered.

We may never know all of the circumstances that led to the death of Reza. Two asylum seekers on Manus Island – one of them a former roommate of Reza – say that “they were forced to retract their eyewitness accounts of violence at the centre in February after being beaten and threatened by Australian officials at the centre.”

They allege they were subjected to “cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment” for days.

Scott Morrison, however, was able to reject their claims, even before bothering with such trivialities as investigating them. This is understandable, again, when one remembers that the point of offshore detention is to be cruel, and to be seen to be cruel.

And so, other reports disappear into moral oblivion. In August, New Matilda published 25 drawings from children in detention, reflecting their trauma.

There were reports of asylum seekers being raped by other detainees on Manus Island.

Back in July, Australia decided it would be a good idea to send Tamils fleeing Sri Lanka back to Sri Lanka. Andrew Bolt, of course, welcomed this practice, and noted, correctly that Bob Carr defended sending asylum seekers back to Sri Lanka.

Bolt also observed that in 2012, the ALP sent asylum seekers back to Sri Lanka. Abbott and Morrison declined to comment on reports that asylum seekers were being returned to the countries where they alleged they faced danger.

Meanwhile, onshore immigration detention also remains as cruel as ever. A Villawood detainee, ABC reported died “after falling from a hospital window”.

Falling?

“Police were called to Liverpool Hospital yesterday morning after reports a 33-year-old man was trying to jump out of a window on the fifth floor. Officers say after several hours of negotiations, the man, from Papua New Guinea, fell from a ledge last night.”

So, ABC reported that he “fell” to his death. After threatening to jump out of a window, and police negotiating with him for hours. Negotiating about what, precisely? Pizza toppings?

When Josefa Rauluni died – hours before he was due to be deported back to Fiji – the Australian also reported that he had “died in a fall”.

And then, a refugee advocate noted: “About 15 minutes before he was due to be handcuffed, he climbed the building where he pleaded to be allowed to stay in Australia, even if it is in detention, as he feared persecution if he returned.”

And then, he jumped.

Rauluni was not the first asylum seeker to commit suicide. We know that Australia’s mandatory indefinite detention policies drive many asylum seekers to self-harm and suicide.

Or as Australian of the Year, psychiatrist Patrick McGorry explained, our detention centres are “factories for producing mental illness”.

We know what will happen. And we knew what would happen when we made our treatment of asylum seekers even more cruel, and even more inhumane.

There is a final point to be made. It is not just asylum seekers who die in custody, and it is not just asylum seekers who Australia subjects to great cruelty.

Consider, for example, the case of Kwementyaye Briscoe.

He was arrested – not because he had committed any crime, but because he was drinking in public in Alice Springs, and so he was taken into “protective custody”.

He was healthy when the police first noticed him – healthy enough to run away from the police. He was then dumped into a cell in an awkward position, with his head “pissing out blood”.

Other prisoners urged the guards to give him medical attention. Whilst they were obliged to check on the prisoners every 15 minutes, they instead opted to ignore Mr Briscoe for hours, until he was dead.

Then there’s the case of Kwementyaye Ryder, who was beaten to death by five white men. The judge proceeded to sentence them leniently, because they were all, in his view, of “good character”.

Or Marlon Noble – an Aboriginal man with an intellectual disability, who was locked up for 10 years without ever having stood trial, for alleged crimes that almost certainly never took place.

He was subsequently released on conditions so stringent that Greens MLC Alison Xannon noted that he “cannot lead a normal life”.

Meanwhile, a few weeks ago, an Aboriginal woman, Julieka Dhu, died after four days in custody for failing to pay a $1,000 fine.

She repeatedly complained that she felt unwell – and was taken to hospital, before being sent back to jail without even having seen a doctor.

In short, there are lots of people who die in Australian custody. There are lots of victims of Australian cruelty.

Asylum seekers and Indigenous people both suffer from extreme and unconscionable cruelty – some of them in Australia, some of them merely under Australian control.

These are due to the policies of our governments, state and federal.

We could effect change. We could start implementing the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody –one might even regard such a move as timely, given that the federal government is currently running two Royal Commissions.

And we could end our cruelty to asylum seekers, and initiate a new era of humaneness to the desperate and vulnerable people who seek our protection.

It is simply a question of whether we act to end Australia’s cruelty.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.