An enduring political myth, propagated by the Murdoch media and largely unchallenged by other media, is that the Coalition is better able to manage the economy than Labor.

So strong is this belief that consumer sentiment improved markedly as a Coalition election victory became more certain. Consumer sentiment has also been boosted by falling nominal interest rates – around two percentage points over the last two years. By some measures, housing interest rates are now at a record low.

In the best of all worlds, reducing interest rates not only lessens the burdens on business borrowers and mortgagees, but also stimulates investment, including investment in housing. Although there is dispute about the extent of our housing shortage, few would question the need to boost the supply of housing.

Easier money and greater confidence, even if based in misplaced faith in the Coalition, will certainly see more buyers wanting to invest in housing. That is, there will be a demand-side response, but will there be a matching response on the supply side?

It is possible that the outcome will be a repeat of housing price inflation, as occurred between 1996 and 2003, with adverse consequences for household debt and foreign debt, and worsening affordability for first home buyers.

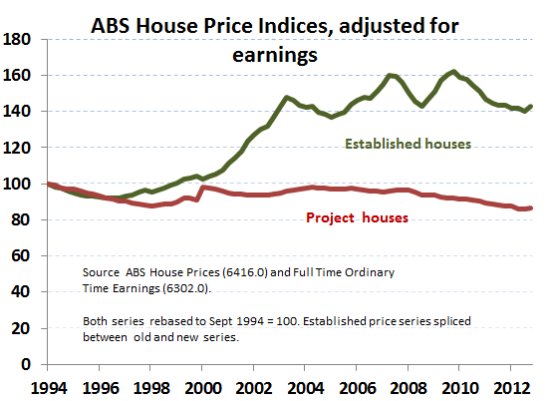

On the supply side there are many reasons to expect a muted response. Because of our urban geography new land releases are remote from employment, service and recreational centres, and are under-served with transport infrastructure. Project houses on urban fringes are not expensive; in fact, in relation to average incomes, they have become more affordable over the last 20 years (see the graph below), but other costs such as commuting are high. Australians want well-located housing.

Urban infill is difficult for reasons to do with aged infrastructure and because new high density housing prompts NIMBY objections. And, since the GFC, property developers have been finding it hard to get project finance. For developers lender caution rather than interest rates are the limiting factor, and hard-nosed financiers have more sense than to believe that a Coalition Government is going to manage the economy better than Labor did.

Then there is the general distribution of wealth and income, coupled with the way lenders assess repayment risk. It’s much easier for someone who already owns a house and has reasonably secure employment to get a loan to buy an established house or to renovate an existing one than it is for someone with insecure income to get a loan. Upgrading our existing housing is strongly supported by its exemption from capital gains tax.

Also Australia’s policy settings are very favourable to those who borrow to buy houses as a personal investment. Our taxation laws allow generous deductions for interest and depreciation, and in recent changes to superannuation rules, self-managed superannuation funds are now allowed to borrow to invest in property, making such investments highly taxation-privileged. Personal investors have very much preferred established properties – not necessarily a wise preference, given the way such properties have risen so much in price, but unsophisticated investors tend to take past gains as indicators of future gains. Such behaviour leads to booms and busts.

And, as I pointed out recently, low nominal interest rates at a time of low inflation encourage mortgage over-commitment.

So as in any situation when more funds are available in a market with supply-side constraints, price inflation is an almost certain outcome. Our houses will get dearer and less affordable. It is hardly surprising then that the Australian Prudential Lending Authority and the Reserve Bank, both in their guarded ways, are warning about a housing boom. Australia’s houses are already highly priced: The Economist, in its regular survey of house prices, finds Australia has some of the most over-priced houses in the world – only Hong Kong, New Zealand and Canada have higher prices.

Booms are followed by crashes, and while we may not experience a US-style crash, we are looking at increasing our already high foreign debt. When we take a mortgage we do so through the domestic market, but our financial institutions, in turn, borrow overseas. Our private debt becomes part of our national debt.

In our dumbed-down economic debate, our foreign debt – the debt which builds up because we import more than we export – has hardly scored a mention. Over the 11 years of the Howard government it rose from around 30 per cent to 50 per cent of GDP, fuelled largely by rising housing debt. There is a notion that foreign debt doesn’t really matter, because it’s all incurred by responsible private financial institutions; the only debt we need worry about is government debt, because, as we are all supposed to know, governments are intrinsically wasteful. It’s a testament to the enduring power of bone-headed ideology that such a notion persists five years after the GFC.

Our foreign debt has stabilised over the last six years, thanks to strong commodity prices. This is about as good as it gets, and the path from here on is for our debt to grow again. If foreigners financing that debt believe it is fuelling a housing boom, we could face a South American style flight of capital with an attendant severe devaluation, rather than the hoped-for “soft landing” for the Australian dollar.

A prudent government would warn about irrational exuberance and follow the lead of the New Zealand and Canadian governments which, in order to head off a boom, have imposed lending restrictions on financial institutions. From a political perspective, however, a housing boom could suit our new government, elected largely on the idea that households are doing it tough, really well.

Let me explain.

As I, and other researchers have verified, there is little evidence to support the idea that we’re all doing it tough; incomes have easily outstripped inflation and the cost of the much-maligned carbon tax. But house price movements help explain the “doing it tough” notion. When house prices rise, as they did over the Howard years, people feel more prosperous, even though all that’s happening is price inflation. When people find that the equity in their houses has risen, many use mortgage redraw to finance consumption, thus increasing their indebtedness.

As Jeffrey Sachs says of the dynamics that led to America’s crisis, people used their houses as ATMs. When housing prices fall, as they have done since 2010, the opposite logic holds, and people feel poorer. The ATM is gummed up – hence the “doing it tough” notion.

Both ways of thinking are irrational. Unless you are about to emigrate, the market value of your house is irrelevant. But from the perspective of a government, exploiting the public’s irrationality, a housing boom can be welcome. Housing booms are slower to develop than stock market booms – a housing boom could well carry the Abbott Government to the next election before crashing. Its benefits, though short-lived, would accrue to middle-aged voters who have housing equity, and these are disproportionally supporters of the Coalition. Its costs would be borne by younger Australians, facing even tougher housing affordability, but they don’t count politically – many are disenfranchised, and the others are hardly Coalition supporters.

Of course interest rates are set by the Reserve Bank, not the Government, but the chairman’s position and three board members positions become vacant within the next three years, and the Government will shortly appoint a new Treasury Secretary, who has an influential ex-officio board position. In view of the Abbott Government’s early moves on senior public servants, we can expect the Reserve Bank to be more subject to the Government’s bidding than in the past. It is notable that soon after news of Abbott’s public sector sackings spread, Reserve Bank Assistant Governor Malcolm Edey softened the Bank’s warnings.The decision by the US Federal Reserve to hold off on “tapering” gives a plausible justification for our Reserve Bank to reduce interest rates.

Then there is the hint of loose monetary policy in Abbott’s statements about welcoming of foreign capital. We are being prepared for yet greater dependence on foreign debt – a debt we will have to repay some day. It looks like a return to the feelgood days of Howard-Costello economics. The bill comes later.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.