Today marks marks the 30th anniversary of a watershed moment in Sri Lankan history: the Black July pogrom against members of the Tamil ethnic group. The pogrom claimed the lives of perhaps thousands of people, displaced thousands more and marked a start to the civil war that would consume the country for nearly 30 years.

Black July and its origins are worth discussing, if for no other reason than the recent attacks on the rights of asylum seekers and the prevailing perception that there is no persecution of Tamils in Sri Lanka.

The pogrom took place in July 1983, by ethnic majority Sinhalese. It was not a spontaneous outburst of violence, as is commonly thought. Rather, it was a well-planned, calculated attack upon the minority group in an attempt to drive them from the island’s main population areas. This was the finding of a detailed report by the International Commission of Jurists following the events.

The Tamil minority on the island had been a marginalised group since the Sri Lankan independence. Contrary to accounts that claim a long historical difference between the two main ethnic groups on the island, the repression and violence against Tamils is a modern phenomenon.

At a time of growing Sinhalese nationalist sentiment, the Tamils were viewed by many as unwanted and alien. Their language was given second-class status when Sinhalese was recognised as the official language on the island by the Sinhalese Only Act of 1958. Peaceful protests against this marginalisation were put down with force by the government and led to the first anti-Tamil riots in 1958.

A growing Nationalist fervour that was taking hold amongst the nation’s Sinhalese political elites, who merged Buddhism with nationalist ideology. Tamils were portrayed as invaders from the Indian subcontinent. This became a powerful tool for politicians to whip up anti-Tamil hysteria amongst the growing urban poor.

When small groups of Tamil separatists began to carry out armed operations in the north to protect their communities against the military, the government stepped up raids into Tamil Jaffna and pushed the local Tamil community to breaking point.

The pseudonymous Sri Lankan writer L Piyadase, in Sri Lanka: The Holocaust and After, details how the pogrom began. A Tamil girl was gang raped by a Sri Lankan military unit in Jaffna on 20 July 1983. Tamil Tiger (LTTE) insurgents ambushed the same unit three days later, killing 13 soldiers in retaliation. When two of these soldiers were to be buried the following day, word spread amongst Colombo’s Sinhalese community that the ambush had taken place. This news brought large Sinhalese gangs to the streets.

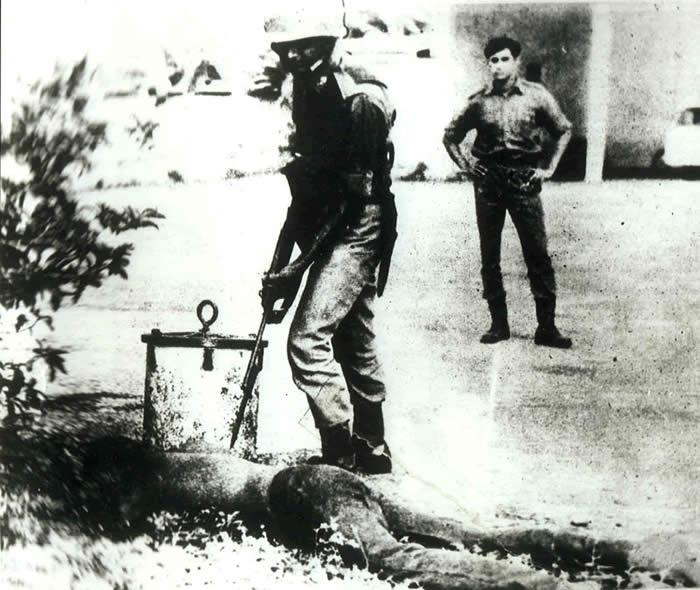

Beginning in Colombo and quickly spreading throughout the country the rioters sought the destruction of the Tamil community. Tamils were singled out in the street, chased and beaten or killed. One Norwegian tourist witnessed a bus of 20 Tamil civilians doused in petrol and set alight.

The riots showed clear signs of prior planning and government collaboration. The rioters were organised in groups who sought out Tamil houses for destruction and appeared to have a detailed knowledge of who lived where and who worked at what business. This is because they had gotten hold of, or more likely were given, voter lists, and so were able to precisely identify their Tamil targets.

Some politicians conceded government involvement. Others had directly incited racial hatred. Industry Minister Cyril Matthew had for years published a series of racist books and pamphlets about Tamils, many of which were used in schools and distributed at government expense. Along with other cabinet ministers Matthew organised and coordinated gangs both before and during the pogrom. The then President Jayewardene was quoted in the New York Times as conceding that members of his party had encouraged the violence, rapes and murder that took place.

The police and military were mostly reluctant to intervene and in cases participated in the killing. The pogram was allowed to happen because of “the active participation or passive encouragement of the ultimate guardians of law and order – the police and the army”, according to Historian SJ Tambiah.

These events, which are commemorated by Tamil communities in Australia, are not isolated instances that began and ended that week. The political corruption and violent nationalism that lead to the pogrom continues today, even though the civil war proper has come to an end.

Today, many Tamils continue to suffer. Human Rights Watch released a report earlier this year documenting the systematic use of rape against Tamil women in both official and secret prison camps. The abuse of civilians within the camps is reported to be widespread. The policy to forcibly move the internally displaced Tamils after the end of the war may actually violate the genocide convention, according to an Australian spokesman for the International Commission of Jurists. The purpose of the camps has been to transfer the Tamil population out of population areas and change their ethnic makeup.

The condition of the Tamils is largely unknown to the Australian public. Our politicians take great care in spinning a different story. However, the torture that Tamils still face is being reported by media organisations like New Matilda, even after Bob Car and Julie Bishop visited Sri Lanka in February, and claimed that Tamils faced no danger.

The British government recently judged whether it was safe to deport Tamils asylum seekers back to Sri Lanka. The test case, which went unreported by the Australian press, concluded with the judgment that the continuing human rights abuses made it unsafe to return people who may be detained by the government’s security apparatus back to Sri Lanka.

This is because "Sinhalisation" is still underway in the traditionally Tamil north of the country. Tamils are slowly being displaced with exclusively Sinhalese social and cultural institutions, violent crackdowns and military occupation, according to the International Crisis Group. This is ethnic cleansing.

Armed gangs stormed through Colombo’s streets 30 years ago, but the pogrom against Tamils continues today.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.