There’s been a polarising, and often vitriolic, debate in the past weeks across the Australian theatre community. Depending on who you ask, the debate has either been between writers and directors, or between young avant-garde innovators and old conservative narrators.

Rosemary Neill, writing in The Australian, found a recent proliferation of adaptations at the expense of original Australian works, and questioned whether reimagined classics should be funded under theatres’ self-defined criteria for new local content, as is currently occurring. She also looked at whether these works are devaluing the role of the playwright, when young directors like Simon Stone cry foul that they are hamstrung by anything other than their own vision.

There’s an assumption that these adaptations have crowded out the original works. I think the adaptations are a symptom – not the cause.

|

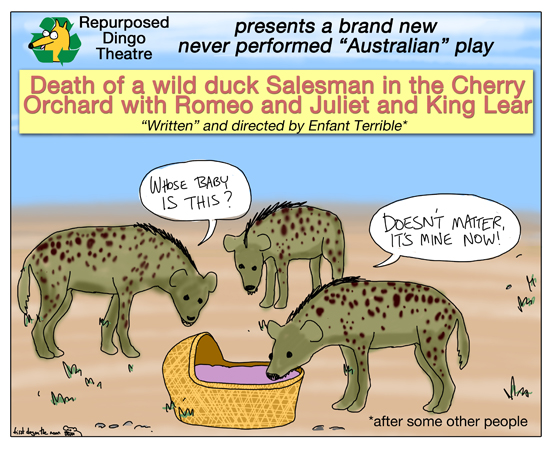

Thanks to First Dog On The Moon. |

In theatre, a new production already proven overseas, or a play long ago established as a classic or crowd-pleaser, no matter how innovative the interpretation, is still a far safer option financially than a new work.

Australian plays show strongly at the box office against foreign work; Australians want to see them. The difference is in the cost of investing in the story itself. Stories for the stage develop and come alive through being workshopped, through the writer seeing the characters come to life and working with them. It takes time, it takes money, and it takes risk – and too few new Australian works are being given that opportunity.

Stone says that writers should spend more time in the rehearsal room to hone their theatre skills — and writers would like nothing more than to do that. A generation ago funds for regional and mid-sized theatres all but evaporated, and with them, the opportunity for most playwrights to explore their work collaboratively in the setting for which it was written. There used to be a minimum requirement for new Australian work – there is no longer.

Yet still six in 10 theatre companies consistently report, in a comprehensive national survey conducted by Playwriting Australia, that they think there should be more Australian work. Only one in six think there shouldn’t.

That one in six are a vocal lot, and lately Simon Stone has led the charge – not just in favour of his own style of visionary re-imaginings, but aggressively and violently dismissive of playwrights and their craft, as if they were the enemy of good theatre, and of audiences.

It seems Stone thinks he is being progressive in his views. In truth it is a tired, banal refrain borrowed from auteur screen directors to claim a "possessory credit" in these most collaborative of creative mediums.

“I am stealing whatever I need to steal, and corrupting whatever I need to corrupt, to entertain an audience”, he says.

It is story that he is stealing, story he is corrupting, and the alchemy of collaboration that he is claiming primary authorship of. To claim primary authorship of a premise, an inspiration, a story, of characters, observations and insights, that somebody else has created, and that you acknowledge having stolen and corrupted, is such patent nonsense. It is an enfant terrible shouting, “Mine!”.

At its very best, theatre serves to reveal the content of a work in the most powerful way, and all the players are together in the service of the story. Using a night at the symphony as an analogy, Stone is the conductor. Without the composer and their creation he’s just an observer at a symphonic jam. Take the musicians away too and he’s just a guy alone on a stage waving his arms around, wishing someone would notice.

To dismiss the works and the artists you base your own work on, when your role is entirely dependent on them, beggars belief. Gifted interpretation and direction can be incredibly inspiring, creative and rewarding, but it is not a superior primary act of creation that nullifies the creation, the talent and the art on which it is based.

It is not a whinge when a writer is hurt or angry that their role – their crucial, pivotal role – is made invisible. Invisible to the audience; that is a win but invisible to your colleagues, your collaborators, your industry commentators and observers; that is a counter-productive, cruel and stupid blight on our industry.

The auteur attitudes espoused by Stone and some others are not widespread, but they have insidiously crept into the industry.

Whether this attitude stems from ignorance, fear, jealousy, or pure greed is irrelevant because everybody loses from this sort of posturing; the audience, and the industry.

Andrew Upton, one of Australia’s most influential creative theatre directors, is quoted as saying that scripts have no intrinsic literary value, that they are blueprints to be used in the act of theatre creation. “We are not writing literature we are writing productions”. Writing for performance requires all the imagination and insight of other writers who start with a blank page, and then another skill altogether is also needed: the vision and humility and craft to envisage actors and others bringing your work to life. That others build upon the creation does not diminish its value, it enhances it.

There is a huge gap between our ability to imagine and our ability for original creation. This is never truer than having an idea for a story, and turning it into a compelling script. Perhaps it is because good writers make this act of original creativity appear effortless that so many think they can do it. Very few can.

If writers are writing for stage and screen it is because they are seeking the alchemy of successful collaboration (rather than the independence of writing books for example). And when writers see work that they’ve loved and tended and nurtured and bled over come to life, this is what makes it all worthwhile. These moments take a team, a true collaboration but one in which the writer should be acknowledged, indeed acclaimed.

Ideas are easy. Turning them into compelling scripts is really bloody hard. That’s what good writers do.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.