The rate at which asylum seekers were granted protection visas by the Department of Immigration (DIAC) since 2006 has fluctuated in accordance with the government — and immigration minister — at the time, raising questions about political influence on the decision making process.

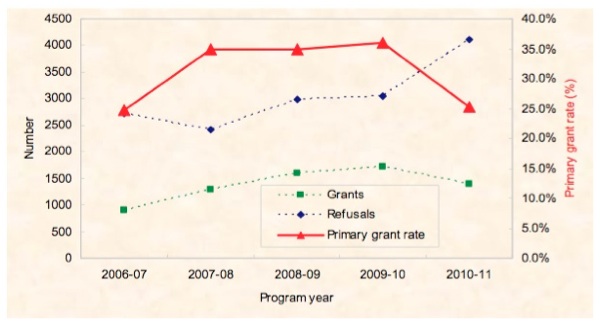

A graph taken from a DIAC publication, Asylum Trends, shows that primary grant rate was at 25 per cent at the end of John Howard’s term in 2006, but increased to over 35 per cent in 2007 when Kevin Rudd won the election and appointed Chris Evans as minister for Immigration. The primary rate dropped again in 2010 when Julia Gillard became prime minister and Chris Bowen was given the Immigration portfolio.

New Matilda contacted long-time Howard government Immigration Minister Philip Ruddock, who denied exerting any influence on departmental decisions during his time in the portfolio. “Caseloads vary depending on the risks those making claims may have faced,” he said. “My view is all decision makers both initial and on appeal should make decisions properly and in accordance with the applicable law.”

Outgoing minister Chris Bowen is yet to reply to similar questions about department policy and whether he exerted influence over decision-making.

But refugee experts tell a different story, especially concerning the intake of refugees subsequent to the Afghanistan and Iraq wars.

The Asylum Seeker Resource Centre’s Kon Karapanagiotidis has over 10 years experience assisting asylum seekers with their claims. He told New Matilda, “Back in early 2000, under the Howard government, the government very much wanted Iraq and Afghanistan to be seen as places where, we’re winning the war on terror and that we’re safe.”

“It was not by accident that, speaking roughly, 70-80 per cent of decisions during that time of Afghanis and Iraqis were being rejected by DIAC — consistently rejected.”

Roz Germov, a member of the Refugee Review Tribunal during the Howard government, told a similar tale: “When I was an RRT member, we had staff at the tribunal who used to be case officers [at DIAC]and they said it was really hard to get an approval up; even if they wanted to,” she said.

“There was a vast improvement with Chris Evans, in terms of how people were treated. He was an excellent Minister,” Germov said. “But after he left, it went back to almost how it was under Philip Ruddock.”

Karapanagiotidis said that over the years he had noticed “patterns and trends around DIAC that emerge; they will take a certain world view on a particular country — ie that country is or isn’t refugee producing — and once that culture sinks in, the reality within that culture is closed and conformist to people following what the directive is.”

Germov told New Matilda there is also pressure on DIAC decision makers to process applications in accordance with strict performance indicators. Processing protection visa applications in a timely manner is a priority for the department; case-workers must process applications within 90 days of their lodgment, a time frame that has become difficult with an increase in boat arrivals and onshore protection visa applications.

Within the 90 day time limit, case officers must obtain a copy of the asylum seeker’s information file through Freedom of Information; gather evidence from experts such as medical reports to corroborate trauma or torture; obtain evidence specific to the country the asylum seeker is fleeing; research and write legal submissions setting out an asylum seeker’s claims and how they fall or don’t fall within the Refugee Convention; and obtain health, security and overseas police clearances.

Despite this, while the number of refugee applications have increased from 3000 in 2002-2003 to over 5000 in the 2011-2012 financial year, the number of trained, operational case managers working on refugee assessments at DIAC has remained the same.

According to a departmental report, there were 67 case officers working on assessing primary application claims in 2002. A statement issued by the department in mid 2012 noted that there were 68 decision makers for onshore clients.

In the last financial year, the average time for deciding applications has dropped to 44 days as compared to 76 in 2010-11.

“It’s easier to reject than to accept,” Germov said. “There’s performance criteria for case officers over how much work they can get through each year. There’s a view that, ‘Oh well I can get my stats up this month and they’ll get a second chance at review anyway.’”

“In a lot of primary decisions, they quote a lot of information and only tend to support the information that suggests things are improving in the country. They are rather selective.”

A spokesperson for DIAC told New Matilda that each case is assessed on its merits and the department’s decision makers are impartial.

“Primary acceptance rates fluctuate over time for a number of reasons, such as the changing composition of caseloads and changing country situations,” the spokesperson said. “However, the point is each person's claims are assessed individually. It would be highly inappropriate for the government to exert pressure on decision-makers as this would compromise the assessment process.”

Read part one of Sasha Petrova's report here. This story was originally written as an assignment in the Masters program in the School of Journalism at Monash University.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.