Some 20 years after the (official) end of apartheid, race still colours almost every national conversation in South Africa. This is something that outsiders find confronting. Even polite dinner discussions raise vexed questions about white economic privilege, affirmative action policies, guilt, responsibility, retribution and blame.

Such themes are also constantly in the media and social landscapes, as well as in humour, mockery, satire and endless negotiations of identity. Despite the African National Congress’s call to a utopian and colour-blind non-racialism, a call still echoed by certain idealistic populists in the South African media, the end of the apartheid did not magically erase race or free South Africans from the categories that have been so divisive and destructive throughout history; in fact, in many cases, racial identities have become stronger, become culturised.

But what are these racial identities? When filling in a government form in South Africa, one is required to define oneself as “black”, “white”, “coloured” or “Indian/Asian”. These types have been inherited from the apartheid era and attract the righteous ire of many South Africans. While irritating people by their very existence, the classifications also come under fire for being so narrow.

In the 1700s, the Cape was one of the most polyglot societies on earth, with people from across Europe, Asia and Africa migrating southwards by choice or force. Despite apartheid’s hysterical social engineering, this mixture is the South African inheritance, and offers a far wider and more hybrid set of possibilities than can be contained in four arbitrary options.

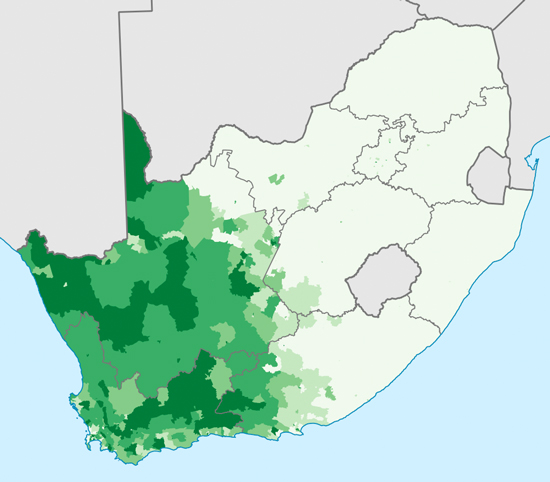

The best example of the continuing weirdness of race in South Africa is the term “coloured”. Long considered an inappropriate word for “black” elsewhere in the Anglophone world, “coloured” here means something very specific. It can be used to mean mixed heritage but is more likely to refer to a cultural grouping of people found largely in the Cape.

Who exactly fits into this category depends on who you ask: they can be defined as descendants of Malay indentured labourers, the original Khoi Khoi indigenous inhabitants, white masters and Bantu slaves, and various other polyglot groupings from within this country’s complicated history. But whichever definitions you encounter, you can be sure that South Africans who talk about being coloured are referring back to a social, cultural and linguistic history that has been a part of the racial landscape for hundreds of years.

Where does that leave bi-racial people? If your mother is, say, a white French woman and your father a black Senegalese man, which bit of the government form are you expected to tick? It’s doubtful whether many people with mixed parentage would intentionally define themselves as “coloured” without belonging to that community. This is particularly the case as this category attracts a stigma in South Africa, where coloureds are seen as neither black enough for black pride nor white enough for white privilege.

And then there’s the question of “Asians”. South Africa is home to large Chinese and Indian communities, both stemming from pre-apartheid immigration and both of which have left their marks on national culture, from the culinary to the political. In fact, Gandhi famously developed many of his ideas during a stint as a lawyer in colonial South Africa.

These groups were classified as “Indian/Asian” during apartheid – but investment trumped skin colour during the days of the boycott. The National Party was desperate to do business with the Japanese — but “Asians” in South Africa were literally second-class citizens — coloureds were third class, with blacks at the bottom of the barrel.

The result? Visiting Japanese businessmen were considered “honorary whites” so that they could stay in the finest hotels and make deals in the finest boardrooms.

In the post-apartheid era there’s been a nifty turn-around. In 2008, Chinese South Africans won a legal battle to be considered previously disadvantaged, which makes them a kind of “honorary black”. This means that they can benefit from black economic empowerment strategies — a development that has been extremely contentious given the sudden increase in Chinese immigration as that powerful economy digs its claws ever deeper into southern Africa.

All of this is without considering the gradation between English and Afrikaans-speaking white people — never mind Portuguese, Italians, Greeks or Jews; or the social and tribal markers that separate Xhosas from Zulus; or the on-the-street hostility faced by Zimbabweans, who look similar and speak similar languages to many black South Africans.

South Africans are engaged in a mass conversation about identity often revolving around the categories bequeathed from the apartheid era. Perhaps this is the real face of Desmond Tutu’s rainbow nation metaphor, one of the things that makes South Africa so infinitely fascinating and difficult for outsiders to grasp: not a harmonious blend of infinite colour but a wild, chaotic clash of hues.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.