Critical reactions to Scott Millwood’s latest documentary, Whatever Happened to Brenda Hean?, reveal a certain lack of insight and imagination in Australia’s critical culture. The problem is not that some critics haven’t liked the film — it’s the fact that none of them have attempted to seriously examine Millwood’s style or consider the film’s key contention.

Several writers expressed frustration at the film’s failure to conclusively answer the question contained in its title, but the real value of Millwood’s work is not about answering that question at all. Through his film and the accompanying book of the same name, Scott Millwood traces a history of violence perpetrated against Tasmania’s environment, and against the state’s green activists, that stretches back over decades. The importance of this work is in the way he shows how that history has a direct bearing on the island’s contemporary political culture.

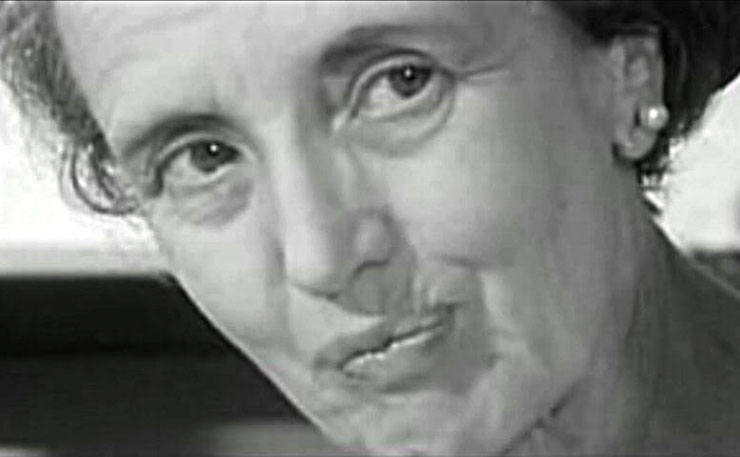

For those not familiar with the Brenda Hean tale, the Tasmanian society lady was a prominent campaigner in the fight to save Lake Pedder, a stunning high altitude body of water in Tasmania’s southwest that disappeared beneath the floodwaters of a hydro-electric dam in the early 1970s. Hean vanished without trace while flying to Canberra in an ancient Tiger Moth piloted by Max Price on 8 September 1972. Three months before the federal election that was to bring Gough Whitlam’s Labor Party to power, Hean was seeking to make the flooding a federal issue by emblazoning “Save Lake Pedder” across Canberra’s skies and lobbying politicians on the ground.

The cursory police investigation that followed Hean’s disappearance failed to shed any light on the activist’s fate. Both she and pilot Max Price had received death threats in the days before the flight, and there was evidence that the plane’s hangar had been broken into the night before they left. Rumours of sabotage and a subsequent cover-up have persisted ever since.

After being handed the police files on Hean’s disappearance several years ago, Tasmanian filmmaker Scott Millwood offered a $100,000 reward for information leading to the solving of the mystery. The film version of Whatever Happened to Brenda Hean? follows the director as he pursues various leads thrown up by the offer, but doesn’t unearth any conclusive evidence.

Besides their disappointment at this perceived failure, many reviewers took issue with Millwood’s constant presence in the documentary, notably an exasperated David Stratton on At the Movies:

“…it didn’t turn out well for me, the documentary, and that’s because Scott Millwood is so insistent in, for absolutely no reason whatsoever as far as I can see, to have himself in all the interviews… Why? I mean I found it really annoying and self-indulgent.”

Leigh Paatsch, in Sydney’s Sun Herald, echoed Stratton’s criticism:

“Dead-ends and red herrings are everywhere, and Millwood’s pedestrian interview techniques — for some strange reason, he insists on being in the frame at all times — just keep drawing your attention to them.”

It’s true Millwood features heavily in the film, and it’s fair enough to question this slightly unusual approach to documentary-making (though the strategy is quite not as rare as the above comments would imply). However, having asked why the director has inserted himself into the film, neither Stratton nor Paatsch make any attempt to understand or explain the decision.

Admittedly, Millwood’s accompanying book provides a much fuller exposition of his creative, personalised approach to Brenda Hean’s story. The book takes shards of documentary evidence — newspaper clippings, police files, and first hand accounts of the Pedder campaign — and interweaves them with a fictionalised treatment of Brenda Hean’s relationship with the Tasmanian wilderness (based on her diaries), her ill-fated flight with Max Price, and back-room discussions between Tasmania’s key political players of the time. Millwood says that the book and the film are “like two halves of a broken whole and in many ways should be read and seen together”.

Unfortunately the simplistic, consumer-guide-style nature of what now passes for criticism in the mass media allows little time for such inter-textual considerations.

In the documentary, and more strongly in the book, Millwood’s investigation of the Brenda Hean case leads him to suggest that the destruction of Lake Pedder, the threats made against Hean and Price, and the mystery surrounding the pair’s disappearance, are all symptomatic of an ongoing cycle of abuse and a culture of silence on the apple isle.

The filmmaker consciously positions himself as an investigator in the project in response to the astonishingly slapdash police work of 1972, and the unanswered questions that have surrounded Hean’s death ever since. To quote the filmmaker, he was “usurping the role of public authority”, because “it became apparent that the truth of what happened to Brenda and Max was not only unimportant at the time, but had been ostensibly avoided”.

Not surprisingly, Millwood’s assertions have raised the hackles of some Tasmanians. Jonathan Dawson, reviewing Millwood’s film on the ABC Hobart website, wrote: “…isn’t it time to let go of the parochial and silly fantasy that Tasmania is somehow darker and more corrupt and secretive than elsewhere”.

Prominent Tasmanian gay advocate Rodney Croome criticised the film in Hobart’s Mercury newspaper for presenting a one-sided “grim, gothic view of Tasmania”. In a blog entry dated October 8, Croome rather smugly suggested that Millwood’s film is all about “incriminating the violence of a patriarchal Tasmania”. If Croome had read Millwood’s book, he would have seen that there is more to the director’s approach than a subconscious desire to wreak revenge on symbols of patriarchal power.

In an evocative chapter entitled “The chair remembers a sapling”, Millwood’s book describes how memories of violence in his family are triggered when he comes across a set of “George Peddle chairs” in the Tasmanian Archives while researching the Brenda Hean case. Peddle was a renowned colonial-era Tasmanian furniture maker, whose blackwood timber is said to have been supplied by one of Millwood’s ancestors. An obsessive collector of these antiques, Millwood’s father told his children: “We must understand that through these chairs, something of the trees and the land of Tasmania belongs to us”.

These memories lead Millwood back to his childhood in a faux colonial mansion built by his father, who affected the airs of the landed gentry and filled his home with colonial portraits and antiques. “And when the house was loaded with these stolen memories he felt safe”, Millwood writes, “because he no longer had to look at his own”. His father’s repressed memories of sexual abuse endured growing up on a working-class dairy farm inevitably resurfaced in other forms, claims Millwood, creating a cycle of violence and secrets within his own family.

Through this highly personal back story, Millwood evokes a particular relationship to Tasmania’s colonial history and the island’s environment that he believes extends well beyond his immediate family. This line of thought is triggered by a comment from the woman who originally handed him the police files on Brenda Hean’s disappearance:

“Tasmania, she said, is like a family in which there is a cycle of abuse. In other places, after 10 or 15 years mysteries are usually cleared up, eventually the truth comes out. In Tasmania it never does … it has always been, keep it in the family, don’t speak of what is actually happening outside, don’t share the secrets … From the time that white people came to Tasmania and displaced and abused indigenous people, there has been a relationship of abuse of the environment. So there is an underlying culture of violence and abuse in one of the most beautiful places of the world.”

Millwood supports this claim with an examination of the drive to dominate and exploit the environment — so neatly reflected in his father’s comments regarding George Peddle’s chairs — that has underlain both sides of Tasmanian politics for decades. In Brenda Hean’s time this was manifest in the virtually unlimited power wielded by the state’s Hydro Electric Commission and their misguided dream of turning Tasmania into an industrial powerhouse. In our own era it is embodied by the loving relationship between various Tasmanian governments and the forestry company Gunns, so ably dissected by Richard Flanagan last year in The Monthly.

To cite two particularly brazen examples of this hand-in-glove bond, following his stint as a rabidly pro-development and anti-green Tasmanian Liberal Premier for much of the 1980s, Robin Gray became a Gunns company director. More recently, during the assessment of the infamous Gunns pulp mill proposal, the then Labor Premier Paul Lennon had his home renovated by the Gunn’s-ownded construction company Hinman, Wright & Manser. The extraordinary lengths Premier Lennon went to in order to ensure the pulp mill went ahead are detailed in Flanagan’s article.

This unrestrained drive to render Tasmania’s environment utterly subservient to the needs of industrialisation and corporate profits has been backed by a sustained history of brutal violence against environmentalists. Millwood’s documentary contains footage of vicious verbal and physical attacks on activists and media personnel. Anyone doubting the savagery directed at environmentalists in Tasmania need only view the footage of an attack using sledgehammers on a car holding protestors recently shot in Tasmania’s Florentine Valley.

Millwood’s book also contains details of a series of anonymous death threats against Tasmanian Greens Senator Christine Milne. When the authorities showed a complete a lack of interest in pursuing the matter, Milne tracked down the culprit without their help. Upon handing a name to police she was told to “forget it”. Similarly, when a logging contractor fired a shotgun at Bob Brown at Farmhouse Creek in Tasmania’s southwest in 1986, the shooter was merely charged with “discharging a firearm on a Sunday”.

Then there is the disappearance of Brenda Hean herself. Even if the activist wasn’t murdered — and there is substantial evidence to suggest that the plane was deliberately sabotaged — the fact that so many are willing to believe she was says much about the political culture south of Bass Strait.

No doubt Millwood’s portrait of Tasmania is selective, and the fact that the island has produced figures such as Brenda Hean, Bob Brown and Christine Milne demonstrates there is a strong culture that runs counter to the island’s ruling ideology. But Whatever Happened to Brenda Hean? does not purport to be a rounded portrait of the state. Millwood uses the Hean story, and his attempts to break the silence surrounding her disappearance, as a means of exploring a particular set of disturbing questions about Tasmania’s political culture, the island’s history, and a unique environment that is slowly but surely being destroyed by an unholy alliance of government and big business.

* Dan Edwards has written about Scott Millwood’s earlier film here.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.