Facing economic headwinds, a restive backbench, and an intractable Senate, the PM will be up against it from day one, writes Ben Eltham.

The cartoonist David Pope is a wonderful illustrator. His latest gem depicts Malcolm Turnbull’s recent election victory.

Drawn as a race car driver, a rather beaten-up Turnbull has arrived at the finish line of the 2016 Australian election, holding nothing but a steering wheel, his vehicle a smouldering wreck behind him. The cartoon is captioned “and with political capital to spare!”

Antony’s calling it: Malcolm over the line, give or take a seat #ausvotes pic.twitter.com/Jsa90Ep0hZ

— David Pope (@davpope) July 8, 2016

The political cartoonist is often a cruel observer, but in this case Pope is being generous. The smoking ruins of the Coalition’s 2016 election campaign have bequeathed Malcom Turnbull little but government itself. The challenges of his second term will begin immediately, and they will get progressively more difficult from today.

Let’s begin with the stern arithmetic of the new parliament. We still don’t know this for certain, but we do know it spells trouble for Turnbull.

The Coalition will likely hold a one or two-seat majority on the floor of the lower house. As Russell Mahoney, Julia Gillard’s former chief spin doctor put it on Twitter recently, “what [the Turnbull government]won’t yet understand – today is the easiest day they’ll get in this term of government.”

Of course, Turnbull won’t find it quite as difficult as Julia Gillard did. The Gillard government didn’t get a majority, and relied on the votes of crossbenchers to govern. Turnbull will have a majority, and the Coalition will be able to govern in its own right. To that it can add the support of a number of independents who have indicated they will support the government against any no-confidence motion, as Cathy McGowan, Andrew Wilkie and Bob Katter have all said they would.

But a majority of one or two is perilously thin. The government needs to find a speaker for the House. If it continues with Tony Smith, a Liberal, then that immediately subtracts a vote. Many votes in the House will thus be close-run things. Crucial legislation will require every single Coalition member to turn up for the vote.

And things can go wrong. MPs can get sick. Or they might be engulfed by scandal, like Craig Thomson was in the Gillard years. Sadly, politicians do die in office – Western Australian Liberal MP Don Randall had a fatal heart attack last year. With a small majority, Turnbull will need to husband every vote. That raises the heat on his government right from the beginning.

The parliamentary numbers give awesome power to any Coalition faction larger than a handful of members. With at least ten MPs, the Nationals will be able to block every single government bill of the new parliament. That gives the leader of the Nationals, Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce, far more sway than the Nationals have enjoyed in recent years. No wonder the new Coalition agreement is being kept secret.

But the real veto will be held by the Liberal backbench. Any sizeable grouping of Liberal backbenchers will be able to defeat a government proposal in caucus, simply by threatening to cross the floor. This will make matters tricky for Turnbull and his cabinet, particularly on sensitive issues like marriage equality or superannuation policy. The rump of Abbott loyalists gathered around his former lieutenants like Kevin Andrews and Eric Abetz are well aware of their ability to disrupt the government. They will be only too happy to exercise their veto, early and often.

And then there’s the Senate. The double dissolution has produced a new upper house of unusual diversity. There will be at least three Xenophon senators. One Nation has won at least two seats, and then there’s Jacqui Lambie, Derryn Hinch and potentially David Leyonhjelm.

This adds up to mayhem. The Coalition needed six crossbench votes in the old Senate to pass legislation – in the new configuration the magic number could be as high as ten.

For the government, none of the permutations are attractive. Legislation with ALP support will pass, but beyond that the government will need to negotiate with several groupings, including Xenophon, Lambie, One Nation and the Greens.

If you hadn’t realised it yet, Pauline Hanson will be a key player in the new Senate. If One Nation ends up with two or even three senators the government will need her in order to pass many bills. But she won’t have the balance of power: no-one will, although the Greens will come close should they secure nine senators.

Whatever happens, one thing is clear: many Coalition laws will die in the Senate. Success will depend on a combination of subtle tactics and skilful negotiation, neither of which have been hallmarks of Malcolm Turnbull’s political career so far.

Let’s leave aside the Parliament for a minute, and turn our minds to the broader policy challenges facing the returned government. There are many of them. The budget, the marriage equality plebiscite, and superannuation are three big issues that are likely to spark trouble in the Liberal party room almost immediately.

On the budget, there are significant spending cuts baked in from previous economic statements by Joe Hockey and Scott Morrison. Some of these began in the 2016-17 financial year that started the day before the election. The funding cuts will mean real pain in areas like aged care and mental health. Universities are also in limbo, awaiting a decision on university fee deregulation (again). Issues like this this will begin to bite as soon as the government gets back to business.

Superannuation is another sore point. The government says it remains committed to its budget package on super, which forces wealthy superannuants to pay higher taxes. But self-funded retirees hate the policy. They and their vocal supporters at the Institute for Public Affairs and the Liberal backbench will press on the issue immediately. A backflip could happen as soon as the Liberal caucus reconvenes.

The marriage equality plebiscite is potentially explosive. This is an issue that threatens to split the Liberal party room right down the middle. Some conservatives will simply never vote for same-sex marriage, whatever the views of the electorate.

The plebiscite, should it be held, will be deeply divisive. It will stir up untold animosities in Australian society. Much of this anger will rebound on the Prime Minister. He is, after all, the man in charge.

But the number one issue of this term of Parliament will be the economy.

Australia’s short-term economic challenges are significant. As New Matilda’s Ian McAuley argued last week, the economy is not growing quickly enough to bring unemployment down, and the risk of a recession is growing. And that’s before we factor in international developments like global financial instability in the wake of the Brexit referendum, or domestic crises like a real estate crash. There’s not a whole lot Turnbull and Morrison can do but wait and hope.

“In a few weeks, the Brexit shockwaves will hit,” McAuley predicted, “but these will be minor compared with the consequences of falls in the dangerously overheated Sydney and Melbourne housing markets.”

The Reserve Bank is also worried. While the RBA has long been cautiously optimistic about house prices, there is no doubt that the current state of the economy is reasonably weak. The RBA’s latest economic statement – issued before the Brexit decision – observes that “non-mining business investment is expected to remain subdued in the near term” and that “leading indicators of labour demand, such as survey measures of hiring intentions, job advertisements and vacancies, have been mixed of late.” As a result, employment growth will slack off. “There is likely to be a degree of spare capacity in the labour market for some time,” the Reserve Bank concludes.

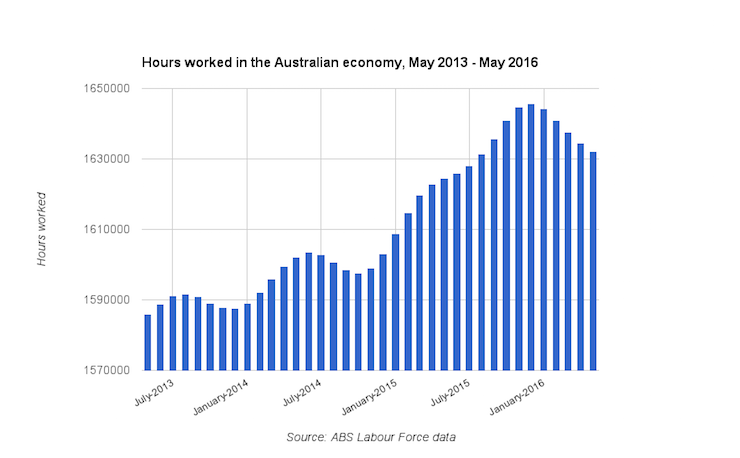

Recent ABS data backs this up. It shows why the Coalition struggled on July 2. The following graph shows the total number of hours worked in the Australian economy over the last three years – a much better measure of the labour force than the unemployment rate.

As you can see, total hours worked grew quite strongly over the calendar year of 2015.

But since January 2016, the trend has been downwards. With wage growth at record lows, and no sign of inflation picking up any time soon, it seems clear that there are real pockets of weakness in the national economy.

Where are those weak pockets? They are in regional Australia, particularly the areas experiencing a rapid adjustment from the heights of the mining boom. Regional Queensland, northern Tasmania, South Australia, and Western Australia are hurting. South Australia has seen barely any employment growth since 2013. Rents in Perth – an excellent proxy for the fly-in / fly-out economy – are down 8 per cent this year. Employment in regional Queensland is falling.

There will be more of this regional pain. The fallout from the end of the resources boom has really only just begun. It is likely to accelerate, as low commodity prices mean more coal and iron ore mines are mothballed or closed. Manufacturing employment is shrinking, and will shrink further as the auto industry shuts down.

In an ideal world, Australia’s low interest rates and flexible economy would buffer this transition. In the capital cities, especially in Sydney and Melbourne, this seems to be happening. But the adjustment in regional Australia will be much more severe.

Managing economic transitions is difficult – just ask Wayne Swan or Peter Costello. Turnbull’s biggest liability remains his Treasurer, Scott Morrison, who has so far proved well and truly out of his depth.

Just how will a Turnbull government deal with an economic downturn? With a restive backbench, a wafer-thin majority and a struggling Treasurer, the government will need to strap in for some very exciting times.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.