I’ve never been patriotic, so Anzac Day has never held much significance for me. Every year it comes by, someone reminds me of it, I briefly remember and then forget it.

This isn’t because my memory is unpatriotic: I forget almost all of the other public holidays every year too. I mostly remember when Australia Day is because I have particular objections to it.

For me, patriotism and nationalism are a bit like religion. I’m not in favour of them, but I think some strains are worse than others. So long as they’re not harming anyone, I’m happy to make peace with people who believe in those sorts of things.

However, when asked I will happily set forth my values, even though they are sharply at odds with those who worship a god, a nation or a state.

As with religion and their various gods, the patriotic and nationalistic have their own forms of blasphemy. In Australia, insulting the valour or judgment of our brave diggers is one such blasphemy. Reverence for Anzac Day has a corollary in anger at those who fail to share this reverence. Murdoch press columnist Miranda Devine wrote about this in her usual style, reviewing a book by right-wing historian Mervyn Bendle.

Devine naturally considers this book “excellent”. Bendle claims that “we witness a sustained new round of attacks on the Anzac tradition from determined ideologues on the far-Left; pampered, well-resourced and influential academics; disgruntled politicians and junior military officers; and their media camp advocates.”

Dr Bendle is concerned that these unpatriotic people advance a “guilt-ridden and self-lacerating historical narrative initiated by [historian Manning]Clark, the New Left, and the feminist movement… post modernists, multiculturalists and post colonial theorists”.

They are led by people like former Prime Minister Paul Keating, “academic historians in elite institutions, including the Australian National University, and (incredibly) the Australian Defence Force Academy, and the Australian War Memorial”.

Passing strange that the people who train the military aren’t militaristic enough for the Murdoch press and its favoured right-wing academics.

As for Anzac Day, I don’t want my position to be overstated. I’m not in favour of heckling during a minute of silence, or harassing people involved in Anzac Day parades. I simply have reservations about the nationalistic way in which I think Anzac Day is interpreted.

In a standard rendition, Devine claims that “our national character was forged” in the invasion of Turkey. This seems to me a rather strange theory.

Devine then went on to quote Charles Bean, who wrote that Anzac stood for “reckless valour on a good cause, for enterprise, resourcefulness, fidelity, comradeship and endurance that will never own defeat”.

Whether this was indeed a good cause – or whether it might have been wise to own defeat in this instance – seem to me at the very least to be debateable propositions.

That our “national character” was forged – and is defined – by a military invasion seems to me to include strong claims not only about what our national character is, but about what kind of values are desirable in a nation.

It seems to me entirely natural that some in Australia might embrace different values. Bullying and abusing those with different political values seems to me rather arrogant, regardless of where one stands on the particular issue in dispute.

What I suspect Devine’s band of unpatriotic rogues find particularly troubling is that there seems to be a deliberate attempt to force this particular brand of nationalism, and the political values that go with it, onto Australians in general.

James Brown wrote that “the centenary will cost Australian state and federal taxpayers nearly $325 million.”

The government’s Anzac Day campaign does not seem like a benign campaign to remember the past, so much as pushing particular values through a particular day of remembrance. Historian Clare Wright observed that “the resurgence in Anzac commemoration has been massive and it was seen that particularly in the late 1970s that Anzac was going to die a rapid death and there were very few people turning it up at all.”

That Anzac didn’t die its natural death, but was consciously resuscitated, naturally raises questions about why that happened, and who in particular invested in the revival.

I don’t think it’s a bad thing to remember Anzac Day, or World War I for that matter. The question of how we remember it, and what lessons we draw from it, however, can be quite different from the preferred conclusions of Miranda Devine.

Consider the not entirely patriotic take by Germaine Greer. She wrote:

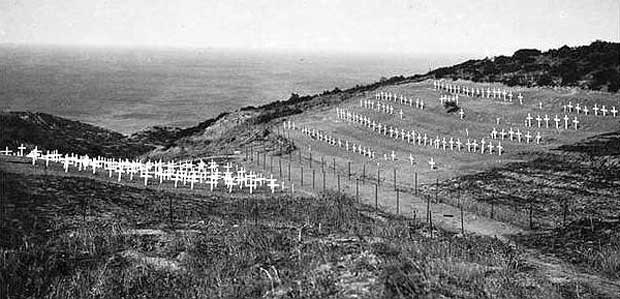

“In the concise words of van Emden, “Just under 40 per cent of Australian males between 18 and 44 enlisted, and of the 331,814 who had served overseas or were undergoing training by November 1918, about 65 per cent were casualties (the highest rate in the British army) and 56,639 had died.” If Australians were such good soldiers, why were nearly two-thirds of them casualties? … Perhaps the bravest thing the Anzacs could have done at Gallipoli in April 1915 would have been to mutiny. “

Her point sounds glib, but is worth serious consideration. The statistics speak for themselves: the Australian soldiers were treated as fodder. Their slaughter was senseless, even if one thought they were fighting for a just cause, which is doubtful.

If we are going to remember the Anzacs, why not remember that Australians were led to their deaths by callous commanders fighting for an unjust cause? This conclusion is no less arguable than Devine’s version. It is simply the kind that very few governments would spend hundreds of millions of dollars on, because it would teach the wrong kind of unpatriotic values. The kind that might lead people to question the wars being waged by our country and its allies now.

Yet if we are to honour people from that time – why only honour those who died in the war? Why not honour those who did their best to stop the slaughter? Why shouldn’t progressives and leftists honour our own fallen soldiers?

Take for example, the Industrial Workers of the World, or Wobblies. Thoroughly radical and proudly disreputable, they campaigned strongly against World War I and conscription in Australia.

Historian Verity Burgmann observed that “a state terrorist campaign against the IWW” was effective in crushing it – even more effective than similar efforts in the United States.

Interestingly, “Engineered in the main by the right wing of the Labor Party, the suppression of the IWW was prompted more by a desire to retain control of the labour movement than by a need to preserve society at large.”

Or consider what we might learn from a different vantage point. Adam Hochschild wrote a great history of the war, focusing on the experience of soldiers, and dissidents who opposed it.

He recounted that before the war, there were large anti-war rallies. There were large socialist parties around the world: the Second International had members from over 30 nations.

It appeared that anti-war sentiment might be successful as the countries drove towards war.

“In the face of mounting tension between their countries, French and German socialists redoubled their statements of solidarity: a leading German socialist promised a congress of the French party, to great applause, "We will never fire on you"; Jean Jaurès addressed comrades in Berlin and returned home to sing the praises of the German Social Democratic Party. When the German party won more than a quarter of the seats in the country's parliament in early 1912, the leading French socialist newspaper was ecstatic, calling the results "a victory of the proletariat as a whole. It is an expression of the universal desire for peace." And, indeed, German socialist parliamentarians, rosettes of revolutionary red in their lapels, continued their long practice of voting against the country's military budget—a budget that was now increasing. “

There was an anti-war demonstration of 100, 000 in Berlin, whilst Jaures “stood before a rally of Belgian workers with his arm around Hugo Haase, co-chair of the German Social Democrats — just the sort of public gesture that enraged ultranationalists in France. He spoke with all the passion of someone who had feared the coming of this moment his whole life; when he finished, the crowd of some 7,000 poured through the streets of Brussels singing” the socialist anthem.

Meanwhile, in England, “Labor unions and left-wing parties organized protest marches that converged for a giant Sunday afternoon antiwar rally in Trafalgar Square, the largest demonstration there in years. Charlotte Despard and other speakers addressed the crowd, which was really waiting for one man, Keir Hardie. To wild cheering, he called for a general strike if Britain declared war. "You have no quarrel with Germany!" he roared. "German workmen have no quarrel with their French comrades…. We are told international treaties compel us [but]who made those? The People had no voice in them!"”

But when war came, the internationalist values evaporated, and nationalistic chauvinism was embraced by the vast majority. For example, the German socialists unanimously voted for war credits – in its private caucus, only 14 of 125 voted against doing so.

The media embraced its traditional role:

Countries vied with each other to declare the war a crusade for the most noble goals. Le Matin, a big French daily, on August 4 called the conflict a "holy war of civilization against barbarity." In Germany the next day, a Social Democratic Party newspaper charged that tsarist Russia "wants to crush the culture of all of Western Europe." In Russia, the leftist writer Maxim Gorky was one of many who signed a statement supporting the fight against the "Germanic yoke." When Ottoman Turkey shortly joined the war on the German side, its sultan declared it was fighting a sacred struggle, or jihad.

Does that remind anyone of the war on Iraq in 2003? Before the war, massive protests against the war. After the war started, it was a noble cause against barbarity the media told us, and opposition mostly died down. The other side of the war naturally mirrored our propaganda but adapted it for the local audience – as the Turkish sultan did, in declaring a jihad, not being as sophisticated as the civilised Europeans who merely called it a “holy war of civilisation”.

As for the unpatriotic – well, 100 years ago, they were derided as cowards and traitors. Today, their lack of patriotism looks a little different, which is a salutary reminder for today’s dissidents. Meanwhile, if the left had been less nationalistic, the war might have been stopped a lot earlier, and a lot fewer people would have died in what was once called the war to end all wars.

No-one expects the federal government to remember the past in this way, and no-one would expect it to spend vast sums promoting a national day which drew these kinds of conclusions. But Anzac Day is treated as though it is non-political, when really it is just based on particular political assumptions that some prefer to remain unquestioned.

It’s not really about remembering the past, and certainly isn’t about understanding it. If we remember the Anzacs, their terrible death toll, and the 65 per cent casualty rate, we might embrace the wrong lessons.

Adopting Greer’s suggestion, instead of embracing nationalistic myths and believing what we are told, perhaps we too should mutiny.

* New Matilda is a small, independent Australian media outlet. We rely almost entirely on reader subscriptions for our survival. If you would like to help us keep reporting, you can subscribe here. Or you can help us by sharing this story on social media (click on the links below).

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.